Albert E. Brumley was basically staring at a cotton field when the spark hit. It was 1929. The world was about to fall into the Great Depression, and life in rural Missouri wasn't exactly a cakewalk. Brumley was picking cotton—a backbreaking, dusty, miserable job—and he started humming a tune. He was thinking about escaping. Not just escaping the field, mind you, but the whole heavy weight of the world.

He later said he was actually thinking about a song called "The Prisoner's Song" while he worked. You've probably heard the story: he took that idea of physical release and turned it into a spiritual breakout. It took him about three years to actually finish the words to song I'll Fly Away, and when it finally dropped in 1932, it didn't just become a hit. It became a permanent part of the American psyche.

The Raw Power of Simple Poetry

Some people look at the lyrics and think they're almost too simple. They're wrong. The genius is in the lack of clutter. You don’t need a theological degree to understand what "Some glad morning when this life is o'er" means. It's visceral. It's the universal human ache for something better than the "shadows" we’re currently walking through.

Brumley was a master of the "white spiritual" or "convention song" style. These weren't meant to be complex operatic pieces. They were meant for people sitting on porch swings or standing in drafty wooden churches. The words to song I'll Fly Away use a repetitive, driving structure that mirrors the rhythm of a heartbeat—or maybe a pair of wings.

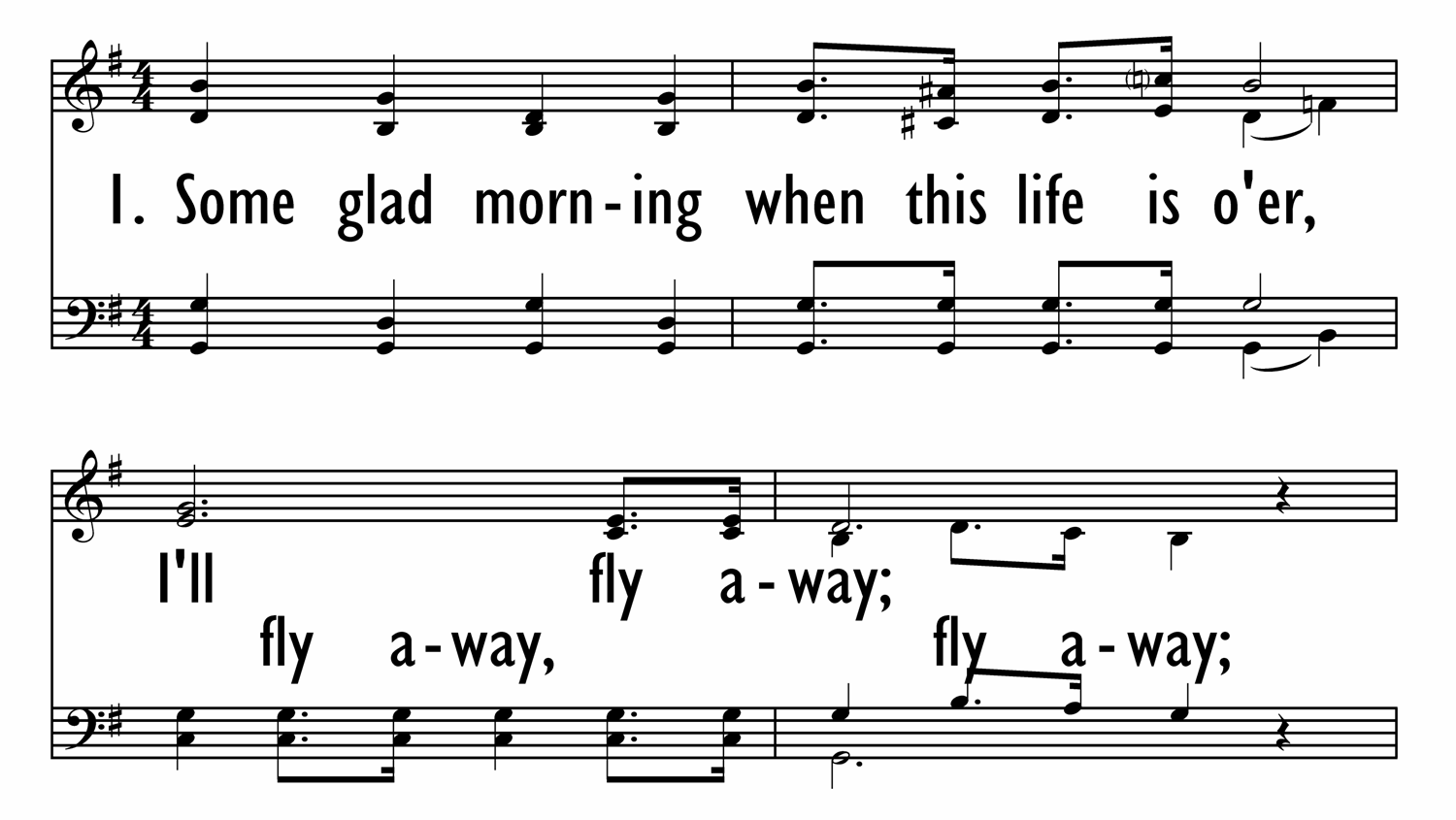

The first verse sets the stage perfectly:

Some glad morning when this life is o'er, I'll fly away.

To a home on God's celestial shore, I'll fly away.

It’s about transition. It’s about the "gladness" of leaving behind a world that can be, frankly, pretty cruel. When you look at the historical context of the 1930s, you see why this resonated. People were hungry. They were losing their farms. The idea of "flying away" wasn't just a metaphor; it was a survival strategy.

Why Everyone from Kanye to Cash Has Sung It

It is legitimately hard to find a song with more covers. We're talking about thousands. Allison Krauss gave it a bluegrass soul. Johnny Cash gave it that gravelly, stoic weight. Even Kanye West included a version on The College Dropout.

Why?

📖 Related: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

Because the words to song I'll Fly Away don't belong to any one denomination or even any one genre. It’s a "crossover" in the truest sense of the word. It fits at a funeral because it offers hope. It fits at a Sunday morning celebration because it’s rhythmic and joyful. It even fits in a secular campfire setting because, at its core, it’s about freedom.

There's a specific tension in the lyrics. You've got the "iron-cold" reality of life ("just a few more weary days and then") contrasted with the weightless imagery of "flying." It’s a song about gravity versus grace. Most of us feel that tension every single Tuesday afternoon.

Breaking Down the Iconic Verses

Most people only remember the first verse and the chorus, but the middle sections are where the real meat is.

The second verse mentions:

When the shadows of this life have grown, I'll fly away;

Like a bird from prison bars has flown, I'll fly away.

That bird imagery is key. Brumley wasn't just being poetic; he was referencing a feeling of captivity. In the 1920s and 30s, the "prison" could be poverty, illness, or just the grind of manual labor. By comparing the soul to a bird, he gives the singer a sense of inherent dignity. You aren't just a laborer or a victim of your circumstances; you are a creature with wings that simply hasn't used them yet.

Then you get to the third verse:

Just a few more weary days and then, I'll fly away;

To a land where joy shall never end, I'll fly away.

"Weary" is the operative word here. Honestly, isn't that how most people feel? Even today, in 2026, with all our tech and speed, the "weariness" is just different. It's digital burnout instead of cotton-picking exhaustion, but the soul still wants the same thing: a land where the joy doesn't have an expiration date.

👉 See also: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

The Secret Sauce: The "Hallelujah" Factor

The chorus is the hook that caught the world.

I'll fly away, Oh Glory, I'll fly away;

When I die, Hallelujah, by and by, I'll fly away.

The inclusion of "Hallelujah" and "Oh Glory" serves a dual purpose. First, it makes the song incredibly easy to sing in a group. It’s an exclamation. Second, it shifts the focus from the act of dying to the act of arriving. Most songs about death are sad. This one is practically a party.

Interestingly, the words to song I'll Fly Away are often credited with bridging the gap between Black gospel and white southern gospel traditions. While Brumley was a white man from the Ozarks, the song’s structure—the call-and-response potential, the syncopated rhythm—borrowed heavily from the African American spirituals he likely heard throughout his life. This shared musical language is why it remains one of the few songs you’ll hear in almost any church across the American South, regardless of the congregation's background.

Misconceptions and Forgotten Facts

One thing people get wrong is thinking this song is a "traditional" spiritual from the 1800s. It sounds old. It feels like it was written in the 1700s alongside "Amazing Grace."

Nope.

It’s relatively modern. It was copyrighted in 1932 by the Hartford Music Company. Brumley actually wrote over 600 songs, including "Turn Your Radio On" and "I'll Meet You in the Morning." But "I'll Fly Away" is his "Stairway to Heaven." It’s the one that paid the bills for his family for decades.

Actually, there was a bit of a legal scuffle over the years regarding the royalties. Because the song is so ubiquitous, many people assumed it was in the public domain. It wasn't. The Brumley family has been famously protective of the copyright, which is their right—it’s the fruit of Albert’s labor in those cotton fields, after all. If you want to use the words to song I'll Fly Away in a movie or on a commercial record, you still have to clear it with the estate.

✨ Don't miss: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

The "Prisoner's Song" Connection

I mentioned earlier that Brumley was inspired by "The Prisoner's Song." If you listen to that old 1920s ballad, the melody is completely different, but the sentiment is there. The original song goes, "Now if I had the wings of an angel, over these prison walls I would fly."

Brumley took that "wings of an angel" idea and baptized it. He moved it from a jail cell to a spiritual plane. That’s the mark of a great writer: taking a secular longing and turning it into a sacred hope.

How to Use This Song Today

If you're a musician looking to cover this, don't play it like a dirge. It’s been done. The best versions—like the one in the movie O Brother, Where Art Thou?—lean into the "flying" part. It should feel fast. It should feel like someone is actually escaping.

If you're just someone who loves the lyrics, take a second to look at the phrasing in the second verse again. "When the shadows of this life have grown." That’s such a beautiful way to describe aging or the closing of a chapter. It’s not dark; it’s just the sun setting before a new morning.

Actionable Steps for Music Lovers and Historians:

- Listen to the "Big Three" Versions: To really understand the range of the words to song I'll Fly Away, listen to the versions by the Chuck Wagon Gang (the original 1930s style), Allison Krauss & Gillian Welch, and the version by Aretha Franklin. Each one emphasizes a different word, a different hope.

- Check the Copyright: If you are a content creator, don't assume this is public domain just because it's "old." Check with BMI or the Brumley estate before using it in a monetized project.

- Study the Meter: If you’re a songwriter, look at how Brumley uses iambic meter. It’s part of why the song is so "sticky." The rhythm of the words themselves mimics the act of walking or breathing.

- Visit the Source: If you’re ever in the Ozarks, the Albert E. Brumley Museum in Powell, Missouri, is a trip. You can see the environment that produced these words. It wasn't a studio in Nashville; it was a rugged, beautiful, difficult landscape that made people long for the "celestial shore."

The song doesn't work because it’s a perfect piece of literature. It works because it’s honest. It admits that life is weary. It admits that we feel like we’re behind bars sometimes. But it refuses to leave us there. It gives us a way out, even if it's just for the three minutes it takes to sing the chorus.

Next time you hear it, don't just hum along. Think about that guy in the cotton field. Think about the "shadows" he was seeing and the "glad morning" he was betting on. That's where the real power lives.