If you’ve ever sat in a dim, wood-paneled pub in Temple Bar or Boston and heard a group of musicians start that driving, rhythmic thrum on a banjo, you know exactly what’s coming. The room gets quiet for a second. Then, someone starts rattling off syllables at a speed that seems physically impossible. They’re singing the words to Rocky Road to Dublin, and honestly, it’s less of a song and more of a linguistic obstacle course.

It’s fast. It’s dense. It’s incredibly Irish.

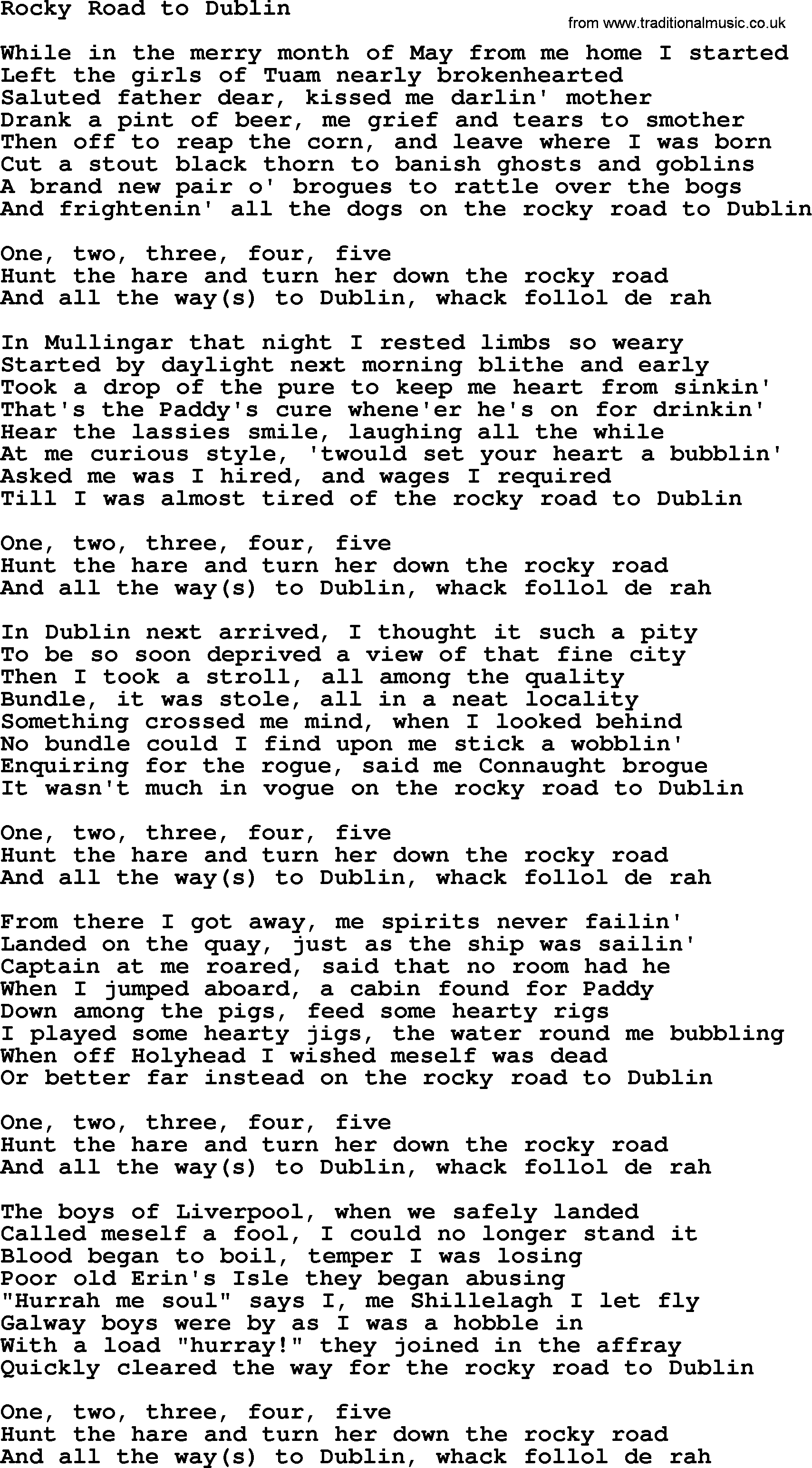

Most people recognize the tune from the Sherlock Holmes soundtrack or maybe a stray The High Kings video on YouTube, but trying to actually memorize the lyrics is a different beast entirely. We aren’t just talking about a chorus and a few verses. We’re talking about a 19th-century travelogue written in a specific meter called "slip jig" time (9/8 time), which basically means the words have to gallop. If you trip over one syllable, the whole thing falls apart like a house of cards.

What are the words to Rocky Road to Dublin actually about?

Most people assume it’s just a "rowdy" drinking song. It isn't. Not really.

Written in the 1800s by D.K. Gavan (often called "The Galway Poet") for the music hall performer Harry Clifton, the song tells a very specific, slightly grim story of a man leaving his home in Tuam, County Galway. He's heading to Liverpool to find work. It’s a migrant’s tale, but instead of being a weepy ballad, it’s packed with defiance, fistfights, and a heavy dose of "don't mess with the Irish."

The journey starts with a "stick of stout blackthorn"—a shillelagh—and a shirt. That’s it. Our narrator walks to Mullingar, gets mocked by the locals for his accent (his "brogue"), and eventually makes it to Dublin. But the words to Rocky Road to Dublin don’t let him rest there. He gets robbed. He sleeps in a ditch. He eventually hops a ship to England where the locals mock him again, leading to a massive brawl where his "Galway boys" back him up.

It’s a story about the friction between the Irish and the English during a time of massive upheaval. When you sing it, you're essentially reciting a rhythmic diary of a man who is exhausted, broke, but absolutely ready to swing a stick at anyone who laughs at his clothes.

The structure that breaks your brain

Why is it so hard to learn? Because of the rhyme scheme.

👉 See also: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

Most folk songs follow an AABB or ABAB pattern. Gavan was more sadistic than that. He used internal rhyming and a "galloping" meter that requires the singer to hit three syllables per beat. Take the opening: "In the merry month of June, from me home I started / Left the girls of Tuam nearly broken hearted."

Then it gets weird.

"Saluted father dear, kissed me darlin' mother / Drank a pint of beer, me grief and tears to smother."

You have to breathe in places you wouldn't normally breathe. If you take a breath at the wrong moment, you'll miss the "Then off to reap the corn" line and suddenly you're three bars behind the fiddle player.

Breaking down the geography

To truly understand the words to Rocky Road to Dublin, you have to map it out. The narrator isn't just wandering aimlessly; he’s taking a very real route across Ireland:

- Tuam: His starting point in County Galway.

- Mullingar: Where he gets mocked by "the girls so fair" for his thick accent.

- Dublin: Where he realizes the city is just as tough as the road.

- The North Wall: The actual docks in Dublin where he boards the ship.

- Liverpool: The final destination where the "Cornwall boys" (English laborers) start a fight.

Why Luke Kelly is the only version that matters

Look, plenty of people have covered this. The Chieftains did a version. Dropkick Murphys gave it the punk treatment. But if you want to know how the words to Rocky Road to Dublin are supposed to sound, you listen to Luke Kelly of The Dubliners.

Kelly was a force of nature. His 1964 recording is the gold standard because he treats the lyrics like percussion. He doesn't just sing them; he spits them out with a staccato rhythm that matches the banjo perfectly. Legend has it that the band practiced the song for weeks just to get the timing of the "One, two, three, four, five" transition into the chorus right.

✨ Don't miss: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

The Dubliners' version popularized the "slip jig" feel. A slip jig is usually a dance—graceful and light. But Kelly turned it into something heavy and muscular. He proved that the song isn't about the melody; it's about the sheer velocity of the storytelling. If you’re trying to learn the song today, do yourself a favor: slow down the Luke Kelly version to 0.75x speed on YouTube. You’ll hear nuances in the pronunciation of "shelterless" and "Mullingar" that you’d otherwise miss.

Common mistakes and "Mondegreens"

Because the song is so fast, people mess up the lyrics constantly. These are called mondegreens—misheard lyrics that take on a life of their own.

One of the most common errors happens in the second verse. The line is "With me bundle on me shoulder / There's no man could be bolder." People often sing "There's no man could be older," which makes zero sense for a young man walking 100 miles to find work.

Another one is the "Merry Month of June." For some reason, people want to sing "The Merry Month of May." Maybe it's because of other folk songs like The Rocky Road to Dublin being confused with The Magpie or something similar. But June is crucial—it’s the start of the harvest season, which is why he’s going to "reap the corn" in England.

Then there’s the ship. "The deck it was my bed / It had no roof upon it."

Think about that for a second. He's crossing the Irish Sea—one of the roughest patches of water in the world—sleeping on the open deck of a steamer. It’s miserable. If you sing it with a big, happy smile, you’re missing the point of the words to Rocky Road to Dublin. It’s a song of endurance.

How to actually memorize this thing

If you’re determined to sing this at your next session, don't try to learn it all at once. You’ll fail. Your brain will melt.

Step 1: Master the "One, two, three, four, five"

The bridge between the verse and the chorus is the hardest part. It goes: "One, two, three, four, five / Hunt the Hare and turn her / Down the rocky road / And all the way to Dublin, Whack-foll-ol-de-ra!"

That "Hunt the Hare" part refers to an old traditional tune. It’s a rhythmic marker. Practice that transition until you can do it in your sleep.

🔗 Read more: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Step 2: Learn the story, not the words

Don't memorize a list of syllables. Visualize the guy walking. He leaves Tuam. He gets to Mullingar. He’s annoyed. He gets to Dublin. He’s tired. He gets on the boat. He’s seasick. He gets to Liverpool. He fights. If you remember the "plot," the words follow much more naturally.

Step 3: Watch your tongue

Irish English (Hiberno-English) uses different mouth shapes than American or Standard British English. To get the words to Rocky Road to Dublin to fit the rhythm, you have to use "flat" vowels. "Dublin" isn't "Dub-lin," it’s more like "Doob-lin." "Tuam" is "Too-um." If you try to enunciate too clearly, you’ll run out of time.

The social impact of the song

It’s worth noting that this song isn't just "folk fluff." It’s a historical document. In the mid-1800s, the Irish were often portrayed in British media as "Simian" (monkey-like) or unintelligent.

The lyrics of this song push back against that. Our narrator is clever. He’s observant. He notices that the people in Mullingar think they’re better than him just because of his accent. When he gets to Liverpool and the locals call him "Paddy," he doesn't take it. He calls on his fellow Irishmen—the "Galway boys"—and they clean house.

The song became an anthem for the Irish diaspora. It’s about the "Rocky Road" of life as an immigrant. It acknowledges that the journey is going to be full of people trying to rob you or mock you, but as long as you have your "blackthorn stick" and a bit of "the real old iron" (meaning courage or a literal weapon), you’ll make it through.

Actionable Next Steps for Folk Enthusiasts

If you want to move beyond just listening and actually master this piece of Irish history, here is how you should proceed:

- Listen to the "Big Three" versions: Luke Kelly (for the grit), The High Kings (for the modern harmony), and The Chieftains with The Rolling Stones (to see how it fits into a rock context).

- Print the lyrics out: Don't look at them on a phone. Use a piece of paper and mark the "beats" with a pen. You need to see where the stresses fall on the syllables.

- Practice the "Slip Jig" rhythm: Clap it out. 1-2-3, 4-5-6, 7-8-9. That is the heartbeat of the song. If you can't clap it, you can't sing it.

- Visit Tuam or Mullingar: If you're ever in Ireland, take the bus. See the road. It isn't as "rocky" as it used to be (it's mostly the M4 motorway now), but you'll get a sense of the scale of the walk.

- Don't rush the chorus: The temptation is to go faster and faster. The best singers actually pull back a little on the "Whack-foll-ol-de-ra" to let the audience catch their breath.

The words to Rocky Road to Dublin represent a masterpiece of 19th-century songwriting. They are a test of memory, a test of breath control, and a tribute to the resilience of the Irish spirit. Whether you’re a performer or just someone who wants to understand what the heck Luke Kelly is shouting about, taking the time to parse these lyrics is a rewarding dive into a world of blackthorn sticks, dusty roads, and the defiant joy of the underdog.