It starts with a simple image. Frosty wind. Moan. Earth as hard as iron. Water like a stone. Honestly, when Christina Rossetti sat down to write the words of In the Bleak Midwinter around 1871, she probably wasn't thinking about a global Christmas hit. She was writing a poem for a magazine. Scribner’s Monthly, to be exact. It was just a bit of verse, a stark, almost bleak meditation on the Nativity.

Yet, here we are over 150 years later, and you can’t walk through a shopping mall or attend a midnight mass without hearing it. Why? It’s because these lyrics don't do the "jingle bells" thing. They don't pretend winter is all hot cocoa and cozy fires. They acknowledge the bite.

The Unexpected History of Christina Rossetti’s Poem

Rossetti was a bit of a powerhouse in the Pre-Raphaelite circle, though she often lived in the shadow of her brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She was deeply, intensely religious. That’s why the words of In the Bleak Midwinter feel so heavy with sincerity. They weren't commissioned by a church. They were an expression of her own Anglo-Catholic faith.

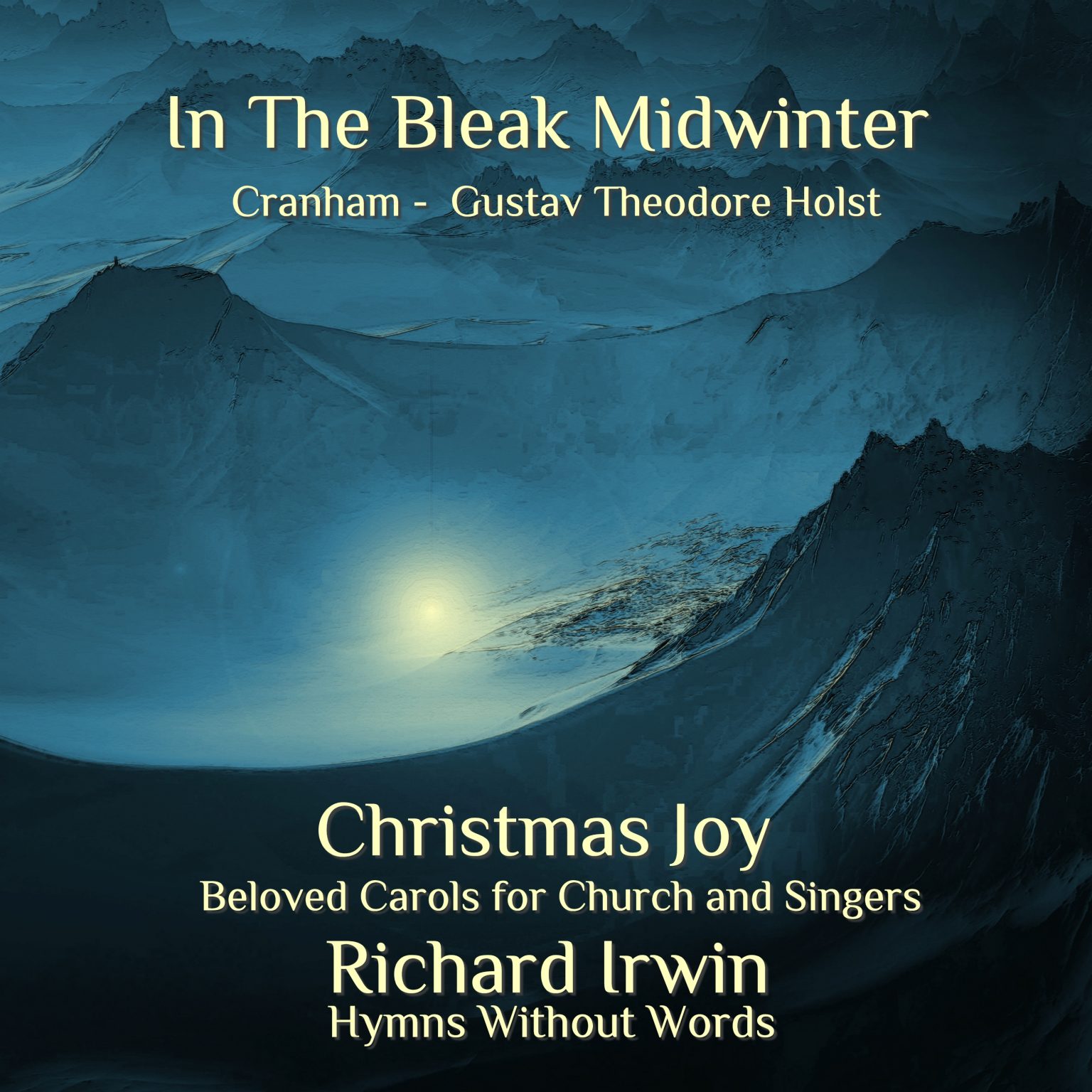

The poem actually sat around for a while before it became a carol. It wasn't until 1906, twelve years after Rossetti died, that it was published in The English Hymnal. The editor? Ralph Vaughan Williams. He’s the one who paired it with the tune "Cranham."

But wait.

If you grew up in a different tradition, you probably prefer the Gustav Holst version. Holst, famous for The Planets, wrote a melody that is arguably more melancholic and, frankly, harder to sing if you aren't a trained choir member. The two tunes have been fighting for dominance ever since. It's a bit of a musical civil war every December.

Dissecting the Imagery: Why "Iron" and "Stone"?

Let's look at that first stanza.

In the bleak mid-winter

Frosty wind made moan,

Earth stood hard as iron,

Water like a stone;

It’s brutal. Most Christmas songs want to talk about "the little Lord Jesus asleep on the hay," but Rossetti starts with the cold. She uses "iron" and "stone" to describe the earth and water. These are dead materials. Inanimate. Unyielding. She’s setting up a contrast between a world that is physically frozen—spiritually stuck—and the arrival of something that can melt it.

💡 You might also like: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

There is a historical inaccuracy here, of course. Bethlehem isn't exactly known for "snow on snow." It’s a Mediterranean climate. In the mid-19th century, Victorian writers loved to transpose the English winter onto the biblical landscape. It made the story feel local. It made the miracle feel like it happened in their own backyard, in the middle of a London fog or a rural snowfall.

The Theological Weight of the Middle Verses

Most people hum along and miss the heavy lifting in the middle of the words of In the Bleak Midwinter. Rossetti starts talking about heaven and earth not being able to sustain "Him."

Heaven and earth shall flee away

When He comes to reign:

This isn't just "baby in a manger" talk. This is cosmic. She’s referencing the apocalypse and the second coming while talking about the first. It’s a very sophisticated theological move. She basically says that the universe itself is too small for the divine.

Then she pivots.

She brings in the "cherubim and seraphim," the "breastful of milk," and the "mangerful of hay." It’s a juxtaposition of the infinite and the intimate. You have the God who makes the heavens flee, and then you have a baby being kissed by his mother.

The "What Can I Give Him?" Problem

The final verse is where the song usually makes people cry. Or at least feel a bit of a lump in their throat.

What can I give Him, poor as I am?

📖 Related: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

It’s the ultimate "relatable" moment. Rossetti lists the options. If I were a shepherd, I’d bring a lamb. If I were a Wise Man, I’d do my part. But I’m not. I’m just me. It’s a clever bit of writing because it puts the listener directly into the scene. You aren't just watching the Nativity; you’re standing there empty-handed in the cold.

The answer she gives—"give my heart"—is almost a cliché now, but in the context of the words of In the Bleak Midwinter, it feels earned. Because she’s already established how cold and hard the world is (iron, stone, bleakness), the act of giving a "warm" heart is the only thing that actually makes sense as an antidote to the winter.

Variations and Controversies: Did She Get It Wrong?

Some critics over the years have pointed out that the poem is a bit... depressing.

The word "bleak" itself comes from the Old English blāc, meaning pale or shining, but by Rossetti's time, it meant desolate. There’s a school of thought that says Christmas carols should be joyous. This isn't. It’s contemplative.

Also, we have to talk about the "snow on snow" line.

Snow had fallen, snow on snow,

Snow on snow,

It’s repetitive. Some editors in the early 20th century tried to "fix" it because they thought it was lazy. They were wrong. The repetition mimics the falling of snow. It creates a rhythmic blanket of sound. If you change it, you lose the atmospheric pressure of the poem.

Why Modern Artists Love These Words

From Katherine Jenkins to Jacob Collier, everyone covers this song. James Taylor did a version. So did Annie Lennox. Why does it work for a pop star as well as a cathedral choir?

👉 See also: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

Basically, it's the lack of sentimentality.

The words of In the Bleak Midwinter are surprisingly gritty. They don't rely on "ho ho ho." They rely on the human experience of waiting in the dark for something to change. In a modern world where Christmas can feel like a consumerist nightmare, Rossetti’s focus on "poverty" and "giving the heart" feels like a radical reset.

It’s also surprisingly short. Five stanzas. Most carols ramble on for eight or nine, losing the plot somewhere around the third mention of frankincense. Rossetti stays focused.

How to Actually Use This Article (Practical Insights)

If you’re looking at these lyrics for a choir performance, a school play, or just your own curiosity, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Mind the tempo: Most people sing this way too fast. It’s a "moan" of a wind, not a gale-force breeze. If you’re performing it, let the silence between the phrases breathe.

- Check the version: If you’re buying sheet music, double-check if it’s the Holst or Vaughan Williams arrangement. They are completely different vibes. Holst is for the "serious" feel; Vaughan Williams (the "Cranham" tune) is for the "sing-along" feel.

- Look at the punctuation: Rossetti was a master of the semi-colon. In the line "Earth stood hard as iron; Water like a stone," that pause is intentional. It’s a separation of elements.

- Consider the context: This was written during a period of "High Church" revival in England. It’s meant to be liturgical.

The words of In the Bleak Midwinter remind us that the season isn't just about the light; it's about the darkness that makes the light necessary. It’s a song for people who find December a bit difficult. It’s a song for the "iron" days.

If you want to dive deeper into the Pre-Raphaelite influence on English carols, look into the works of William Morris or the other poems in Rossetti’s collection Goblin Market and Other Poems. You’ll find a recurring theme of nature being used as a metaphor for the human soul’s struggle.

Next time you hear that first line, don't just think about snow. Think about the "hard as iron" earth and what it takes to break through it.

Actionable Steps for Further Exploration

- Compare the Tunes: Listen to the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, perform the Darke arrangement (a variation of Holst) and then find a recording of the "Cranham" tune. Notice how the emotional weight shifts.

- Read the Original Manuscript: Look up the 1872 version. Sometimes modern hymnals change "thy" to "your" or swap out words like "cherubim" to make it easier for modern congregations. The original is always punchier.

- Explore Rossetti’s Other Work: If you like the mood here, read A Birthday. It’s the flip side of the coin—pure joy and lush imagery—showing she wasn't always "bleak."