You probably remember the smell. That specific, slightly musty, papery scent of a Little Golden Book. For millions of us, our first trip to the Emerald City didn't happen on a movie screen or through L. Frank Baum’s original 1900 novel. It happened on those thin, cardboard-feeling pages bound by a iconic strip of gold foil tape. The Wizard of Oz Golden Book is a weirdly specific piece of cultural DNA. It’s a condensed, vibrant, and sometimes surprisingly dark introduction to a world where monkeys fly and shoes are—depending on which version you’re holding—either silver or ruby.

It's just a kids' book, right? Not really. It’s actually a fascinating case study in how we preserve myths. If you look at the different editions released since the mid-20th century, you can see the tug-of-war between the 1939 MGM movie and the original book.

The Battle Between Ruby and Silver

Most people don't realize that the Wizard of Oz Golden Book has gone through several incarnations. The most famous one, illustrated by Rita Berman in the 1950s, had to navigate a tricky legal landscape. Back then, the imagery from the Judy Garland movie was strictly controlled. This is why, in many early Golden Book versions, Dorothy doesn't look like Judy. She’s often a generic, blonde farm girl. And those famous slippers? In the original book by Baum, they were silver. In the movie, they were changed to ruby to pop against the new Technicolor film.

Golden Books often went back to the silver. It feels wrong to a kid raised on the movie. You're looking at the page thinking, Wait, where’s the red? This choice wasn't just about being faithful to the source material. It was about licensing. By sticking closer to the public domain book, Western Publishing (the folks behind Little Golden Books) could avoid paying massive fees to the movie studios. It’s a bit of "business logic" that ended up shaping how a whole generation perceived the story. You had kids who knew the "movie version" and the "book version," and the Golden Book acted as this weird, hybrid middle ground.

Why the Art Still Holds Up

Let’s talk about the illustrations. Honestly, some of them are kind of haunting. The 1950s art style had this soft, gouache texture that made the Wicked Witch look less like a movie villain and more like a fever dream. The scale was always a bit off, too. In the Wizard of Oz Golden Book, the Scarecrow often looks genuinely stuffed with straw—lumpy and precarious—rather than just a guy in a costume.

🔗 Read more: All I Watch for Christmas: What You’re Missing About the TBS Holiday Tradition

There is a specific kind of magic in the way these books were paced. You have to fit a whole epic journey into 24 pages. This means the transition from the dull, sepia-toned Kansas to the vibrant Munchkinland happens in the turn of a single page. It’s jarring. It’s effective. It mirrors the shock Dorothy feels.

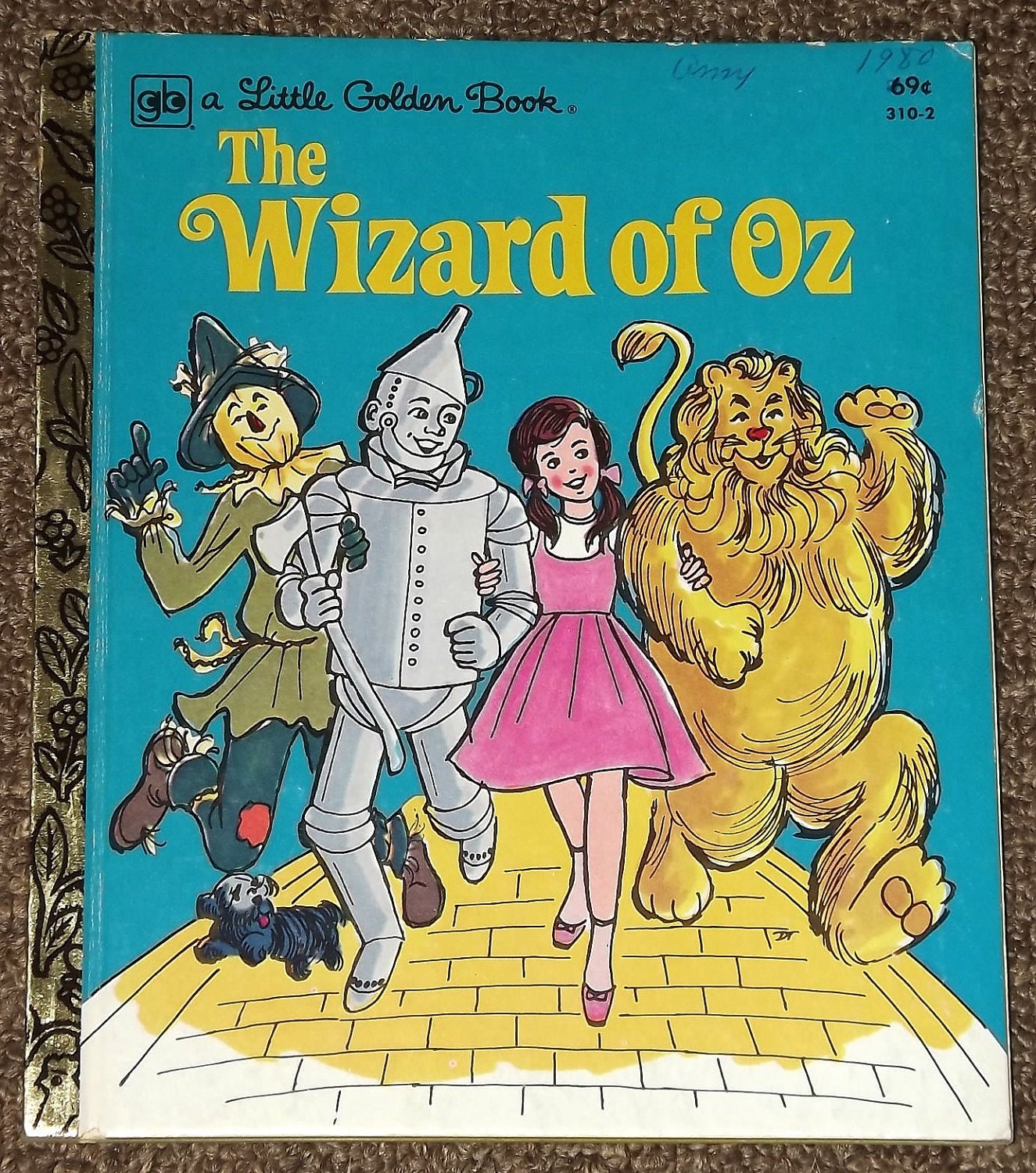

The 1970s and 80s Refresh

By the time we got to the versions illustrated by Kathy Mitchell in the late 80s, the "look" changed again. These versions are much more lush. The colors are deeper. This is the version many Millennials grew up with. Mitchell’s work brought a romanticism to Oz. The Emerald City actually looked like it was made of jewels, not just green painted blocks.

- The Berman editions (1950s): Minimalist, bright, slightly abstract.

- The Mitchell editions (1980s/90s): Detail-oriented, classic fantasy, very "storybook."

- The "Movie Tie-in" editions: These eventually used actual stills or direct likenesses, losing a bit of that unique artistic soul in the process.

The "Golden Book" Effect on Literacy

Experts like those at the National Center for Families Learning have long pointed out that the format of the Little Golden Book was revolutionary. They were cheap. You could buy them at the grocery store for a quarter. Before this, "nice" books were for the library or wealthy homes. By putting the Wizard of Oz Golden Book in a spinning rack next to the milk and eggs, the story became universal.

It wasn't just a story anymore; it was a commodity that every child could own. This accessibility is why Oz remains our primary American fairy tale. We didn't learn it in school; we learned it while our parents were bagging groceries.

💡 You might also like: Al Pacino Angels in America: Why His Roy Cohn Still Terrifies Us

Collecting the Gold: What to Look For

If you’re digging through a thrift store bin, don’t just grab the first copy you see. Look at the spine. The "A" edition is the first printing. It’s usually hidden in the back near the spine on the last page. A pristine 1950s "A" copy of the Wizard of Oz Golden Book can actually fetch a decent price among collectors, though most of them have been loved to death—scribbled in with crayons or had the gold foil chewed off by a toddler.

There’s also the "Big Golden Book" version. Same story, bigger pages. It’s less iconic but way better for actually seeing the brushstrokes in the art.

Honestly, the "errors" are the best part. You’ll find versions where the Tin Man’s funnel hat is missing in one frame or where the Cowardly Lion looks suspiciously like a house cat. These aren't bugs; they're features of a pre-digital publishing world where artists worked on tight deadlines to meet the demands of a hungry, post-war audience.

The Story That Never Dies

We keep coming back to Oz because it’s a story about "enoughness." Dorothy has everything she needs the whole time. The Wizard of Oz Golden Book simplifies this message so purely that even a three-year-old gets it. No complicated subplots about the politics of the Winged Monkeys. Just: Walk the path, find your friends, realize you’re already home.

📖 Related: Adam Scott in Step Brothers: Why Derek is Still the Funniest Part of the Movie

It's a heavy concept for a book that costs less than a cup of coffee.

But that’s the genius of the format. It takes these massive, sprawling myths and shrinks them down to fit in a child’s hand. You don't need a three-hour film or a 300-page novel to understand the fear of the forest or the disappointment of finding out the "Great and Powerful Oz" is just a guy behind a curtain. You just need a few well-placed sentences and some evocative art.

How to Use This Knowledge Today

If you're looking to introduce a child to Oz, or if you're a collector, here is the move. Don't just buy the newest edition on Amazon.

- Seek out the vintage editions: Go to eBay or local antique malls. Look for the Berman illustrations from the 50s or 60s. The color palette is fundamentally different from modern printing and offers a more "authentic" vintage experience.

- Compare the text: Read a Golden Book version alongside the first chapter of Baum's original. It’s a great way to show kids how stories change when they are retold. Point out the silver vs. ruby slipper discrepancy. It turns a simple storytime into a lesson in critical thinking.

- Check the spine code: If you are buying for investment, always check the letter in the back. An "A" or "B" printing is what you want. Anything past "E" is common.

- Preserve the foil: If you have an old copy with the gold foil peeling, don't use clear Scotch tape to fix it. The acid in the tape will eat the paper over time. Use archival-safe glue or just leave it—the "distressed" look is part of the history.

The Wizard of Oz Golden Book isn't just a relic. It’s a bridge. It connects the 19th-century imagination of L. Frank Baum to the modern digital age, reminding us that no matter how much technology changes, we’re all still just looking for a way back home.