You’ve probably seen it a dozen times. That sudden, violent explosion of Technicolor when Dorothy opens the door to Munchkinland remains one of the most iconic moments in cinema history. But honestly, The Wizard of Oz 1939 film is a bit of a miracle when you look at how close it came to being a total disaster. It wasn't just a movie; it was a chaotic, dangerous, and wildly expensive experiment that almost bankrupt MGM.

Most people think it was a massive hit from day one. It wasn't. While it did okay at the box office, the sheer cost of production meant it didn't actually turn a profit for the studio until it was re-released years later. It’s funny how time changes things. Today, we treat it like a sacred text of Hollywood, but in 1939, it was just another "troubled production" trying to compete with Gone with the Wind.

The Messy Reality Behind the Emerald City

Making The Wizard of Oz 1939 film was basically a nightmare for everyone involved. You’ve heard the stories about the makeup, right? Buddy Ebsen was the original Tin Man. He didn't quit because of "creative differences." He literally almost died because the aluminum powder makeup coated his lungs, causing a total respiratory collapse. He spent time in an iron lung while the studio just went ahead and replaced him with Jack Haley. They didn't even tell Haley why the first guy left; they just switched to an aluminum paste instead of powder.

And then there’s Margaret Hamilton. She played the Wicked Witch of the West with such terrifying precision that she gave generations of kids nightmares. During the scene where she disappears in a cloud of smoke in Munchkinland, the trapdoor failed. The pyrotechnics went off early. Her green copper-based makeup caught fire. She ended up with second and third-degree burns on her face and hands.

The crazy part? After she spent weeks recovering, she refused to work with fire again, but she still came back to finish the movie. That’s the kind of grit that defines this era of filmmaking. It was dangerous, unregulated, and frankly, a little bit insane by modern safety standards.

💡 You might also like: Actor Most Academy Awards: The Record Nobody Is Breaking Anytime Soon

The Technicolor Secret

Everyone talks about the color, but few people realize how physically painful it was to achieve. Technicolor in the late 1930s required an incredible amount of light to register on the film stock. We’re talking about set temperatures that regularly soared above 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Imagine being Bert Lahr, trapped inside a costume made of actual lion skins—yes, real lion hide—under those burning lights. He was constantly soaked in sweat, and the costume had to be placed in an industrial dryer every night just so it wouldn't rot.

Why The Wizard of Oz 1939 film Is More Than Just a Kids' Movie

There is a depth to the storytelling that gets lost if you only watch it as a fairy tale. Some critics argue it's a political allegory about the Populist movement, with the Scarecrow representing farmers and the Tin Man representing industrial workers. Others see it as a psychological journey.

Honestly, it’s probably both.

The film arrived at the tail end of the Great Depression. When Dorothy sings "Over the Rainbow," she isn't just a bored teenager. She’s a girl living in a sepia-toned world of poverty and dust storms, dreaming of a place where "troubles melt like lemon drops." That resonated deeply with 1939 audiences. They knew what it felt like to live in a gray world and hope for something better.

📖 Related: Ace of Base All That She Wants: Why This Dark Reggae-Pop Hit Still Haunts Us

Directors and Changes

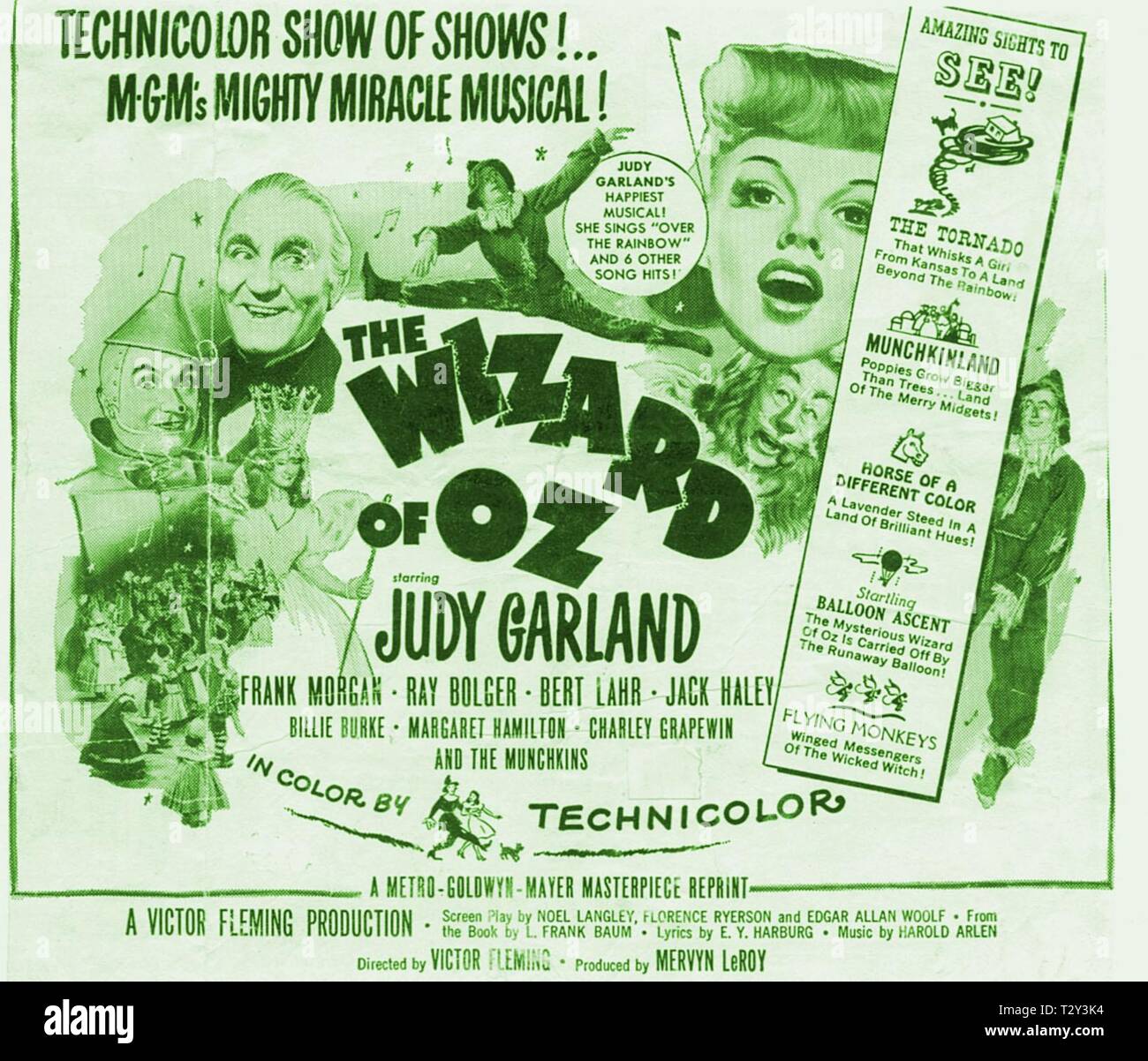

Did you know the movie had four different directors? Richard Thorpe was the first, but his vision didn't quite work (he originally had Judy Garland in a blonde wig with tons of makeup). George Cukor came in briefly and told them to strip all that off and let Judy look like a normal girl. Then Victor Fleming took over and did the bulk of the work. When Fleming was called away to "save" Gone with the Wind, King Vidor stepped in to film the Kansas sequences.

It’s a miracle the movie feels cohesive at all. Usually, "too many cooks" ruins the soup, but in this case, each director seemed to add a necessary layer.

The Music That Almost Wasn't

Can you imagine this movie without "Over the Rainbow"? It almost happened. The suits at MGM thought the Kansas sequence was too long. They felt a slow ballad slowed down the pace of the opening. They also thought it was "undignified" for a star like Judy Garland to be singing in a barnyard.

Thankfully, associate producer Arthur Freed and vocal coach Roger Edens fought for it. They knew that without that song, we don't understand Dorothy's heart. We don't care if she gets home because we never saw her yearning to leave.

👉 See also: '03 Bonnie and Clyde: What Most People Get Wrong About Jay-Z and Beyoncé

The music, composed by Harold Arlen with lyrics by Yip Harburg, provides the emotional glue for the entire experience. It’s sophisticated. It’s haunting. It doesn't talk down to children.

Common Misconceptions and Urban Legends

Let's clear some stuff up.

- The Hanging Man: No, a Munchkin actor did not hang himself on set. That dark shape you see in the background of the woods is a large bird (a crane or an emu) borrowed from the Los Angeles Zoo to make the set feel "alive."

- The Pink Floyd Thing: "Dark Side of the Rainbow" is a fun coincidence, but the band has repeatedly stated they didn't record the album to sync with the movie. The human brain is just really good at finding patterns where they don't exist.

- The Ruby Slippers: In L. Frank Baum's original book, the shoes were silver. They were changed to ruby red specifically to take advantage of the new Technicolor process. Red popped better against the yellow brick road.

Actionable Insights for Film Buffs and History Fans

If you want to truly appreciate The Wizard of Oz 1939 film beyond a casual viewing, there are a few things you should do. First, watch it on a high-quality 4K restoration. The detail in the matte paintings—the backgrounds that were hand-painted on glass—is staggering. You can see the brushstrokes. It’s a lost art form.

Second, look at the casting of the "Kansas" characters versus the "Oz" characters. The fact that the farmhands and the professor appear in both worlds reinforces the idea that Oz is a projection of Dorothy’s subconscious mind trying to process her real-life anxieties.

- Compare the Book: Read L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. It’s much darker. The Tin Man’s origin story is basically a horror movie involving a cursed axe.

- Check the Costumes: Pay attention to the Cowardly Lion’s face. The prosthetic was made of foam latex, a brand-new technology at the time. It was so delicate it had to be replaced almost every day.

- Visit the Smithsonian: If you’re ever in D.C., you can see a pair of the actual ruby slippers. They are one of the most visited artifacts in the National Museum of American History.

The film is a testament to what happens when artistry, ego, and sheer luck collide. It shouldn't have worked. It was a logistical disaster and a financial risk. Yet, nearly a century later, we’re still talking about it. That’s the real magic.

To get the most out of your next viewing, pay close attention to the transitions. Notice how the camera moves through the "sepia" door into the color set. That wasn't a digital effect; they painted the inside of the farmhouse sepia and had a stand-in for Judy Garland dressed in a sepia outfit open the door. The real Judy, in her blue dress, then stepped into the frame. It’s a simple, brilliant practical effect that still works perfectly today. Look for the slight "glitch" in the lighting when the switch happens; it’s a beautiful reminder of the human hands that built this masterpiece.