You’ve definitely seen them. Those clunky, oversized files ending in .bmp that seem like relics from a 1990s dial-up modem era. While modern formats like WebP or HEIC try to squeeze every kilobyte of data into tiny, efficient packages, the Windows bitmap file format just sits there. It's uncompressed. It's heavy. Honestly, it’s a bit of a dinosaur.

But here’s the thing: it’s a dinosaur that still runs the world in ways you might not expect.

If you’ve ever opened Microsoft Paint, you’ve used a BMP. If you’ve ever looked at a Windows desktop wallpaper from 1998, you’ve seen a BMP. While the tech world has moved toward lossy compression to save space, the BMP remains the "raw" baseline for digital imagery on Windows systems. It’s the digital equivalent of a slab of uncarved marble.

What exactly is a Windows bitmap anyway?

At its heart, the Windows bitmap file format is a map. Literally. It’s a "bit map."

Unlike a JPEG, which uses complex math like Discrete Cosine Transform to "guess" what pixels should look like to save space, a BMP is basically a spreadsheet of colors. It tells the computer: "Pixel 1 is Red, Pixel 2 is Red, Pixel 3 is slightly darker Red." It doesn't try to be clever. It just lists the data. This is why a 1080p BMP file is massive compared to a JPEG of the same image.

Most people think BMP is just one thing, but it’s actually evolved quite a bit since Microsoft and IBM first dreamed it up for OS/2 and Windows 3.0. You’ve got different "bit depths." A 1-bit BMP is just black and white—nothing in between. Then you jump to 4-bit (16 colors), 8-bit (256 colors), and the standard 24-bit "TrueColor" which gives us the millions of colors we’re used to seeing today.

The architecture of a .bmp file

If you were to open a BMP file in a hex editor, you’d see a very specific structure. It’s not just a pile of pixels.

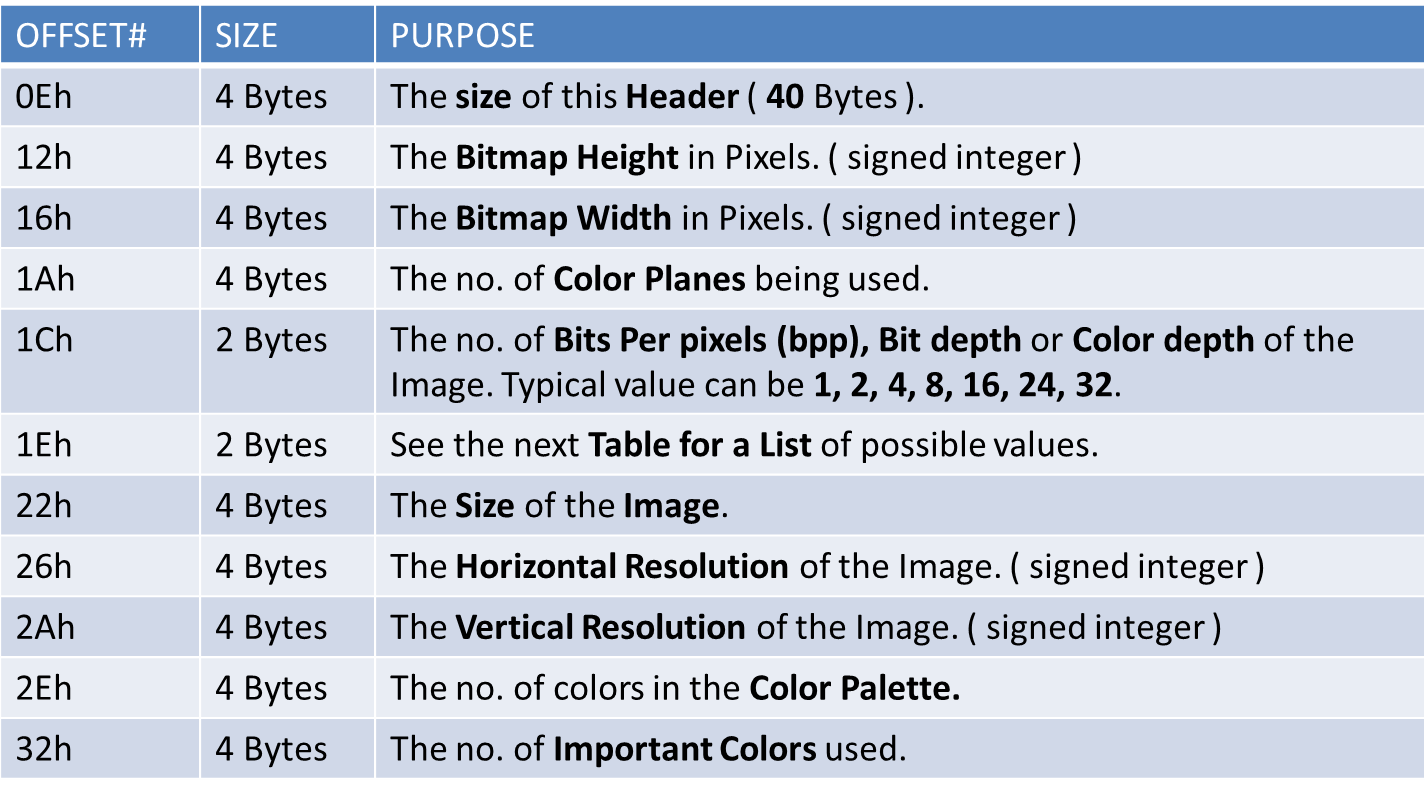

First, there’s the File Header. This is the first 14 bytes. It starts with the characters "BM"—the magic cookie that tells the OS, "Hey, I’m a bitmap!" If those two letters aren't there, the file won't open. Next comes the DIB Header (Device Independent Bitmap). This part is crucial because it describes the dimensions. It tells the software how wide and tall the image is, and more importantly, how many bits are used per pixel.

Interestingly, BMPs are usually stored bottom-up.

Yeah, it’s weird. Most image formats start at the top-left and read like a book. Windows bitmaps often start at the bottom-left and scan upwards. Why? Because that’s how the old GDI (Graphics Device Interface) in Windows was designed to handle memory. It’s a legacy quirk that persists to this day.

Why developers still use the Windows bitmap file format

You might wonder why any sane developer would use a format that eats up so much disk space in 2026.

Complexity is the enemy of speed in certain niche applications. Because the Windows bitmap file format is uncompressed, a programmer doesn't need a heavy library or a complex "decoder" to read it. You just open the file, skip the header, and dump the pixel data directly into the graphics card’s memory. It’s incredibly fast to process because there’s no "unzipping" happening behind the scenes.

In industrial imaging, medical scanning, or simple hardware firmware, BMP is king. If you’re writing code for a tiny microcontroller that controls a screen on a coffee machine, you don’t have the CPU power to decode a PNG. You just want the raw bits. BMP gives you that.

- Transparency issues: Standard BMPs didn't really do transparency for a long time. While later versions (BITFIELDs) allow for an alpha channel, it's notoriously buggy across different image viewers.

- Zero Loss: Every time you save a JPEG, you lose a little bit of quality. A BMP is a perfect 1:1 representation of the original data every single time.

- The "Device Independent" part: The "DIB" in the header means the image should look the same regardless of whether you're viewing it on a high-end monitor or an old CRT. It carries its own color table.

The dark side of BMP: Why we stopped using it for the web

The internet killed the BMP. Well, for general use, anyway.

Back in the 90s, if you tried to load a high-res BMP on a 56k modem, you’d be waiting through your entire lunch break just to see a single photo. A 1024x768 image in 24-bit color takes up about 2.25 Megabytes. That same image as a JPEG? Maybe 150 Kilobytes.

There’s also the issue of metadata. BMP is notoriously bad at storing things like EXIF data (the info that tells you what camera was used or the GPS coordinates of a photo). It was built for Windows, by Windows, and it never really played well with the metadata standards that the photography world adopted.

Misconceptions about BMP compression

Here is a fact that usually surprises people: BMP can be compressed.

It’s called RLE (Run-Length Encoding). It’s a very simple form of lossless compression. If you have a row of 500 white pixels, instead of writing "white, white, white..." 500 times, RLE just says "500 white pixels." It’s great for icons or logos with flat colors, but it’s absolutely useless for photos where every pixel is a slightly different shade. Most modern software doesn't even bother with RLE bitmaps anymore, but the capability is buried in the file spec.

The legacy of the DIB

The DIB (Device Independent Bitmap) concept was revolutionary when it arrived. Before DIBs, images were often "Device Dependent," meaning they were tied to the specific color capabilities of the video card that created them. If you moved a file from a machine with a VGA card to one with a Super VGA card, the colors might look totally wrong.

The Windows bitmap file format solved this by including a color palette or a specific color space definition in the file itself. It was one of the first major steps toward making digital art portable across different hardware.

✨ Don't miss: How to share a private video youtube: The Weird Rules Most People Miss

Practical advice for handling BMPs today

If you’re a photographer, don't use BMP. Use RAW or TIFF.

If you’re a web designer, don't use BMP. Use WebP or SVG.

However, if you are a hobbyist game developer or someone working with legacy Windows software, knowing how to manipulate the Windows bitmap file format is like knowing how to fix an old carburetor. It’s fundamental.

When you need to convert a BMP, use a tool that respects the header integrity. IrfanView or GIMP are much better at handling the "weird" variations of BMP (like the 16-bit or 32-bit versions) than the basic photo viewers built into mobile phones.

Next Steps for Implementation:

- Audit your assets: If you have an old application folder taking up gigs of space, search for

.bmpfiles. Converting these to PNG can save up to 80% of space without losing a single pixel of quality. - Use for testing: If you're learning graphics programming, start by writing a BMP parser. It's the easiest way to understand how computers actually "see" images.

- Preservation: If you have 20-year-old family photos in BMP format, keep them as is or move them to a lossless format like PNG. Avoid converting them to JPEG, as you'll be introducing compression artifacts into a perfectly preserved digital original.

The BMP isn't going anywhere. It’s the "plain text" of the image world—simple, bulky, but incredibly reliable when everything else fails.