W.B. Yeats was having a rough time in 1916. He was fifty-one, his heart was basically a disaster zone thanks to Maud Gonne, and he was staying at Coole Park, the Galway estate of his friend Lady Gregory. It’s a damp, grey sort of place in the west of Ireland. He walked down to the lake and saw them. Fifty-nine swans.

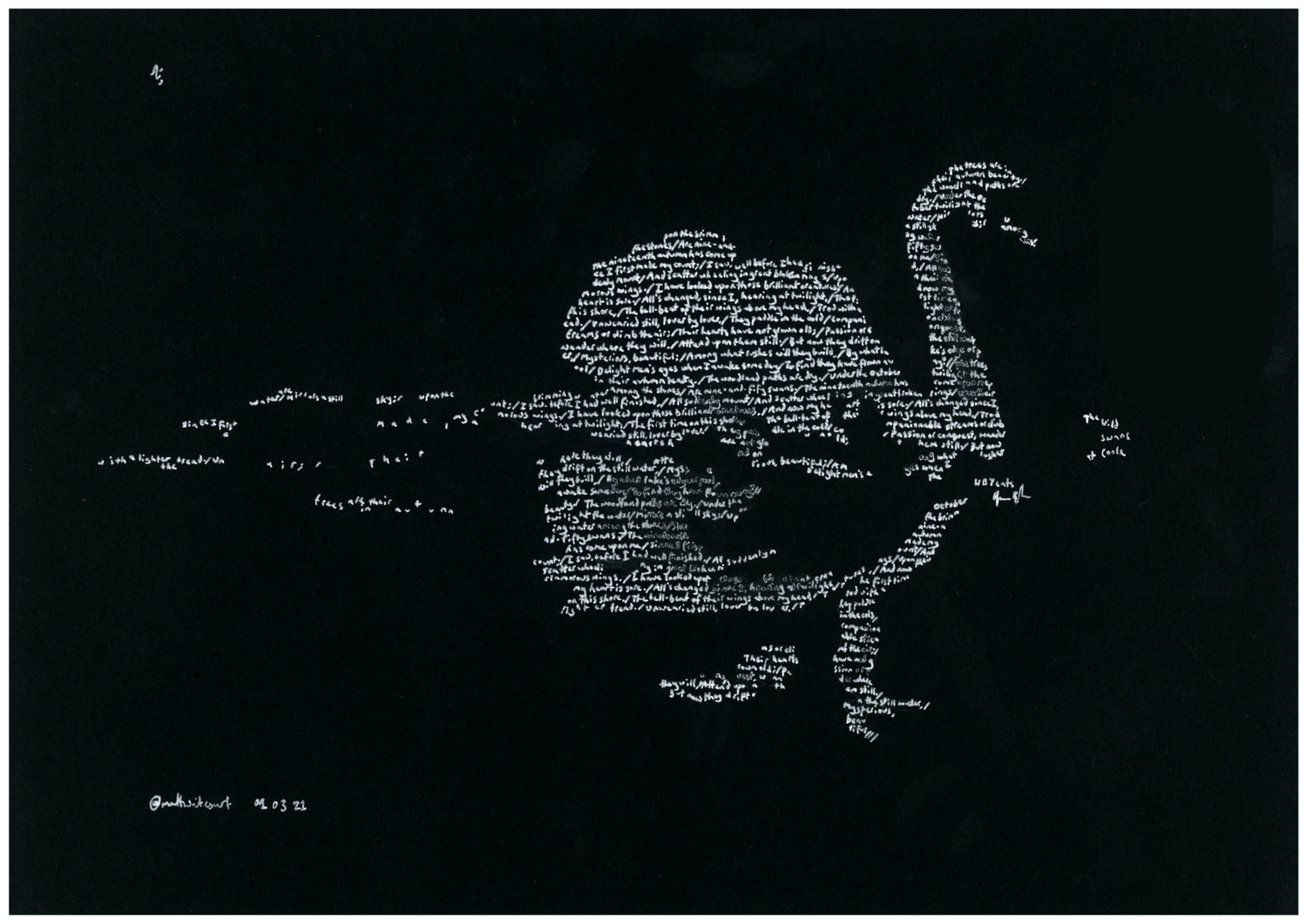

That moment birthed The Wild Swans at Coole, a poem that most of us had to suffer through in school but few actually "get" until they’ve felt the sting of getting older. It isn't just about birds. It’s a midlife crisis set to rhyme.

You see, Yeats had first visited this lake nineteen years earlier. Back then, he had a "lighter tread." He was young, idealistic, and probably didn't have a sore back after a long walk. By 1916, everything had changed. The world was at war. Ireland was reeling from the Easter Rising. Yeats looked at the swans and realized they looked exactly the same as they did two decades ago. They were "unwearied." They still loved. They still paddled in the cold water. Meanwhile, he felt like he was falling apart.

The Brutal Honesty of The Wild Swans at Coole

Most nature poetry is about how pretty things are. This isn't that. Yeats uses the The Wild Swans at Coole to highlight a terrifying truth: nature doesn't care about you. It doesn't age with you. Those swans are "brilliant creatures," but their brilliance makes his own decay feel worse.

There's a specific bit where he describes them suddenly taking flight before he can finish his count. They wheel in "great broken rings" upon their "clamorous wings." It’s loud. It’s chaotic. It’s physical.

If you've ever looked at a photo of yourself from twenty years ago and felt a weird pit in your stomach, you understand this poem. Yeats is doing that, but with swans. He’s obsessed with the fact that their hearts "have not grown old." They still have passion. They still have "conquest." He, on the other hand, is standing in the "twilight" of his life.

Why the number fifty-nine matters

People get weirdly hung up on the count. Why fifty-nine? It’s an odd number. It implies one swan is alone. Maybe it’s a reflection of Yeats himself—the odd one out, the solitary man watching the pairs of lovers from the shore. Or maybe he just counted fifty-nine swans. Honestly, with Yeats, it's usually both. He loved symbolism, but he also spent a lot of time actually staring at that water.

Coole Park Today: More Than Just a Poem

If you go to Gort, County Galway today, you can actually visit the site of The Wild Swans at Coole. It’s a National Nature Reserve now. Lady Gregory’s house is gone—demolished in 1941, which is a tragedy—but the "autograph tree" remains. It’s a massive copper beech where the giants of the Irish Literary Revival carved their initials.

- W.B. Yeats

- George Bernard Shaw

- Sean O'Casey

- John Millington Synge

They all stood there. They all looked at that same water.

✨ Don't miss: Ladies Short Sleeve Cotton Pajamas: Why Your Sleep Quality Depends on a Simple Fabric Choice

The lake itself is a "turlough," which is a seasonal lake found in limestone areas of Ireland. It disappears and reappears depending on the water table. This adds a layer of ghostliness to the whole thing. The landscape Yeats described is literally a vanishing act.

The Real History Behind the Verse

While the poem feels timeless, it was written during a period of intense personal and political stress. Yeats had recently proposed to Maud Gonne’s daughter, Iseult, after being rejected by Maud for years. Iseult also said no. He was adrift.

The "autumn" setting of the poem isn't just a season. It’s a metaphor for his life. October. The end of the year. The end of his youth.

He notes that "all’s changed" since he first stepped on the shore. This is a callback to his other famous 1916 poem, Easter, 1916, where he writes that "all changed, changed utterly." The world was breaking, and the swans were the only things staying the same.

What Most People Miss About the Ending

The final stanza of The Wild Swans at Coole is kind of a gut punch. He wonders where they will be tomorrow. He imagines waking up one day and finding them gone, having flown away to provide "delight" to other men.

It’s a realization of his own mortality. One day, the world will go on, the swans will be beautiful for someone else, and he won’t be there to see it. It’s a bit dark, really. But that’s why it sticks. It’s not a Hallmark card. It’s a raw confession of the fear of being forgotten and the envy we feel toward things that seem immortal.

Getting the context right

If you’re studying this or just trying to sound smart at a dinner party, remember that Yeats published this as the title poem of his 1917 collection. Later, he moved it around in his Collected Poems, but it always served as a bridge between his early, flowery, "Celtic Twilight" phase and his later, more cynical, modernist style.

He was moving away from fairies and toward the hard reality of bones and cold water.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Yeats’ Galway

Don't just read the poem. If you want to actually connect with the vibe of The Wild Swans at Coole, you need to see the landscape that shaped it.

- Visit Coole Park in the late autumn. Go in October or November. You want that "brimming water among the stones" feel. The crowds are gone, and the grey Galway sky does most of the heavy lifting for the atmosphere.

- Check out Thoor Ballylee. Just a few miles from Coole is the Norman tower house Yeats bought and renovated. It’s where he lived while writing much of his best work. Standing in that tower makes you realize how isolated and intense his life was.

- Read it aloud by the water. It sounds pretentious, but Yeats wrote for the ear. The rhythm of the poem matches the sound of rowing or the steady beat of wings.

- Look for the Turlough. Research the water levels before you go. If it's been a dry spell, the lake might be a field. If it's been raining (it's Galway, it probably has), the water will be right up to the treeline.

- Study the Autograph Tree. Bring a guide or use an app to identify the carvings. Seeing the physical marks left by Yeats and his peers grounds the poetry in real, physical history.

The power of this work isn't in its rhyme scheme or its place in the "canon." It’s in the way it captures that universal moment when you realize you aren't the young person you used to be, but the world hasn't stopped to notice. The swans are still there. The water is still cold. And we, like Yeats, are just passing through.