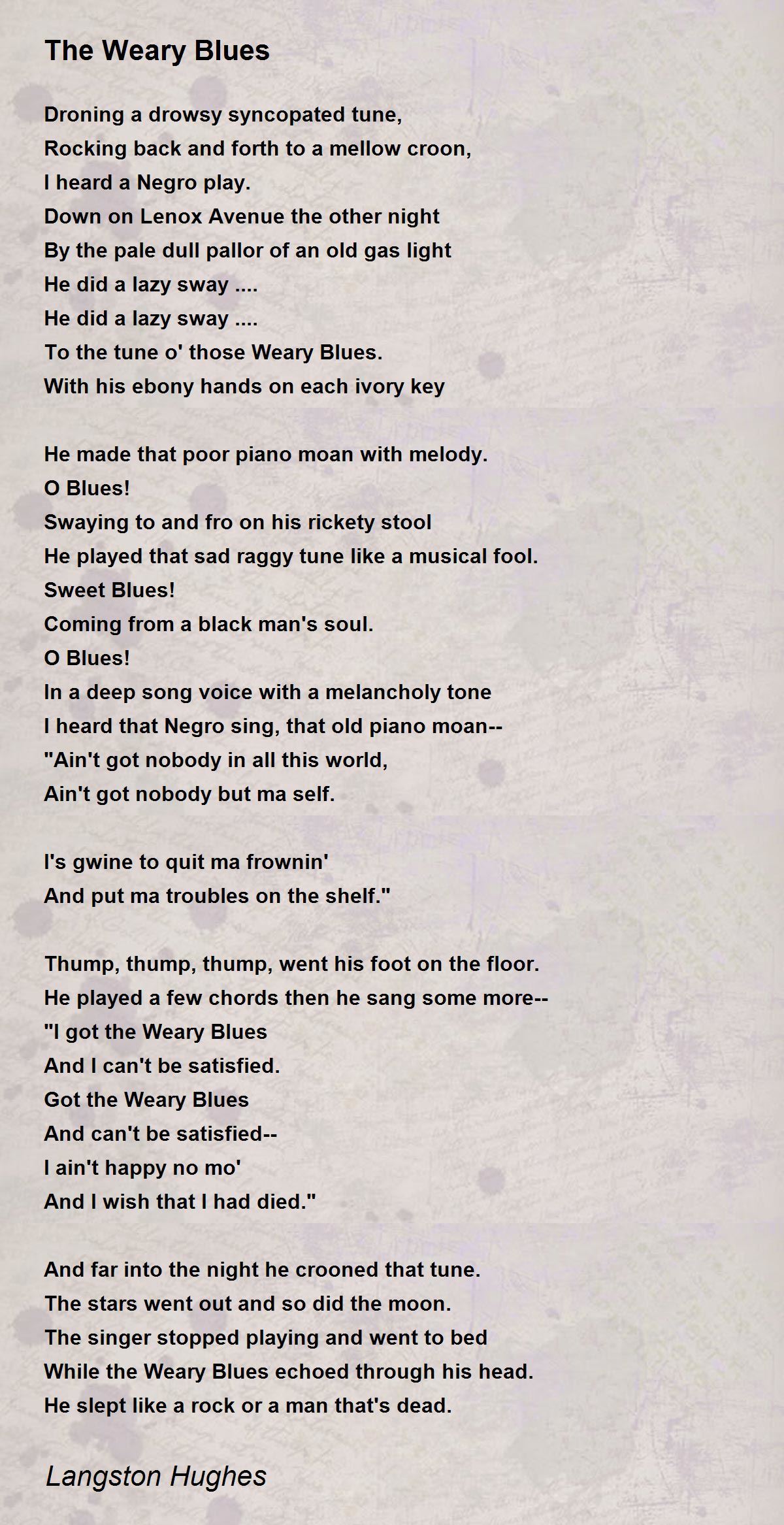

Langston Hughes was only twenty-three years old when he changed the trajectory of American literature with a single poem. It wasn't just some dusty academic exercise. Honestly, when you read The Weary Blues today, you can almost smell the thick haze of cigarette smoke and hear the out-of-tune upright piano groaning in a cramped Harlem basement. It’s raw. It's loud. It’s incredibly lonely.

Hughes didn't just write a poem about music; he tried to make the paper itself bleed the blues. He was sitting in a cabaret on 135th Street, watching a musician sway back and forth on a rickety stool, and he realized that the traditional "high-brow" poetry of the time couldn't capture that feeling. You can’t use Shakespearean sonnets to describe a man whose soul is leaking out through his fingertips onto ivory keys. So, he broke the rules. He used the rhythm of the streets.

The Night Everything Changed for Langston Hughes

The year was 1925. Hughes was a literal busboy at the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington, D.C., when he slipped three of his poems next to the plate of Vachel Lindsay, a famous poet of the era. One of those was The Weary Blues. Lindsay was floored. He told the world he’d discovered a "busboy poet," a label Hughes hated, by the way, but it put the work on the map.

Later that year, the poem won first prize in Opportunity magazine's literary contest. This wasn't just a win for Hughes; it was a flag planted for the Harlem Renaissance. He was saying that the Black experience—specifically the urban, gritty, musical reality of it—was worthy of the highest art. Most people don't realize that the poem actually incorporates lyrics from a real blues song he heard. When he writes "Ain’t got nobody in all this world," he isn't just being poetic. He’s sampling. He was the first "remix" artist of the literary world.

Think about the structure for a second. It doesn't follow a steady heartbeat. It’s syncopated. It sways.

"He did a lazy sway. . . / He did a lazy sway. . . / To the tune o’ those Weary Blues."

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

That repetition isn't an accident. It mimics the "AAB" pattern of traditional blues music. You say the line, you repeat the line with a slight variation, and then you bring it home with a rhyme that feels like a punch in the gut. Hughes was obsessed with the idea that the blues was a laugh-cry. It’s a way of dealing with pain by turning it into something beautiful, or at least something shared.

Decoding the Sound of the Harlem Renaissance

If you want to understand why The Weary Blues is so significant, you have to look at the "syncopated tune" Hughes describes. In the 1920s, there was this massive tension between Black intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois, who wanted "respectable" art to prove Black equality, and younger artists like Hughes, who wanted to show the world as it actually was—liquor, sadness, thumping feet, and all.

Hughes wasn't interested in being "respectable." He was interested in being real.

The poem describes a pianist playing on "Lenox Avenue" under the light of a "melancholy working-man’s lamp." Notice the word choice there. It’s not a "bright" lamp or a "beautiful" lamp. It’s a working-man's lamp. Everything in the poem is exhausted. The piano "moans." The stool "creaks." Even the stars go out by the end. This is a poem about the bone-deep fatigue that comes from living in a world that doesn't want you to succeed.

Why the Piano is "Poor"

Hughes calls it a "poor piano moan." Some critics, like Arnold Rampersad, who wrote the definitive biography of Hughes, point out that this personification is everything. The instrument isn't just an object; it’s an extension of the performer’s body. When the pianist "thumped the floor" with his foot, he wasn't just keeping time. He was grounding himself. He was literally hitting the earth to make sure he was still there.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

There's a specific moment in the poem that trips people up. The speaker says the musician "stopped playing and went to bed," and then adds that he slept like a "rock or a man that’s dead." That’s heavy. It suggests that the only relief from the "weary blues" is a sleep so deep it mimics non-existence. The music doesn't "cure" the man's sadness. It just helps him carry it until he can pass out.

What Most People Miss About the Rhythm

A lot of high school English teachers will tell you this poem is just about jazz. They're sorta right, but they're missing the darker undercurrent. Jazz is usually associated with energy and improvisation, but the blues is about the "low-down" feeling.

Hughes uses onomatopoeia—words that sound like what they mean—to bridge that gap. "Thump, thump, thump" goes the foot. "Bang, bang, bang" goes the piano. It’s percussive. If you read it out loud, you start to nod your head without meaning to. That was intentional. Hughes once said that jazz was a heartbeat, and the blues was the ache in that heart.

He also plays with the concept of the "New Negro" movement. While others were writing about African heritage and ancient history, Hughes was looking at the guy playing piano in the middle of the night because he couldn't go home yet. He found the "ancient" in the "now." He saw the spirituals of the past evolving into the blues of the present.

The Lasting Legacy of the Weary Blues

You see the fingerprints of this poem everywhere today. You see it in hip-hop, where artists tell stories of struggle over a repetitive beat. You see it in the "Slam Poetry" movement. Without Langston Hughes breaking the "ivory tower" of poetry to bring in the sounds of the street, we might not have the lyrical freedom we take for granted now.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Honestly, the poem is a vibe. It’s a mood. It’s that feeling you get at 3:00 AM when the world is quiet and your problems feel way too big for your room.

It’s also important to remember that Hughes was criticized for this. Some Black critics felt he was leanng too much into "low-life" culture and reinforcing stereotypes. But Hughes didn't care. He wrote a famous essay called The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain where he basically said: "If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too." The Weary Blues is the perfect embodiment of that "ugly-beautiful" philosophy.

How to Actually Experience the Poem

Reading it on a screen is one thing, but if you really want to "get" it, you need to hear it.

- Find the recording. There is a famous 1958 recording of Langston Hughes reading The Weary Blues backed by a full jazz band (including Charles Mingus). His voice is surprisingly calm, which makes the lyrics hit even harder. The contrast between his steady narration and the chaotic brass behind him is incredible.

- Look at the line breaks. Notice how some lines are short and others drag out? Read it with that tempo. Don't rush.

- Research the setting. Look up photos of 1920s Lenox Avenue. Visualizing the environment helps make the "pale dull pallor" of the light feel more real.

Actionable Insights for Readers and Students

If you’re studying this for a class or just because you’re a fan of the Harlem Renaissance, don't just look for "themes." Look for the "weary."

- Analyze the color palette: Hughes uses "dull," "pale," "black," and "ivory." It’s a high-contrast, moody scene. Why no bright colors? Because the blues isn't colorful; it's a shadow.

- Identify the shift: The poem starts with the observer watching the musician, but by the end, the observer’s voice fades and the musician’s lyrics take over. The music consumes the poem.

- Compare to modern lyrics: Take a song by an artist like Kendrick Lamar or J. Cole and look at how they use repetition and rhythm to talk about systemic exhaustion. You’ll find that the "weary blues" hasn't gone away; it just changed its tune.

The real power of The Weary Blues is that it doesn't offer a happy ending. The man doesn't win the lottery. He doesn't find love. He just plays until he can't stay awake anymore. And sometimes, just being able to turn that exhaustion into a song is the only victory we get.

To truly understand the depth of this work, your next step should be to listen to the blues musicians Hughes loved—people like Bessie Smith or Ma Rainey. Listen to the way they slide into notes and hold them just a second too long. That "slide" is exactly what Hughes was doing with his words. Once you hear the music, you'll never read the poem the same way again.