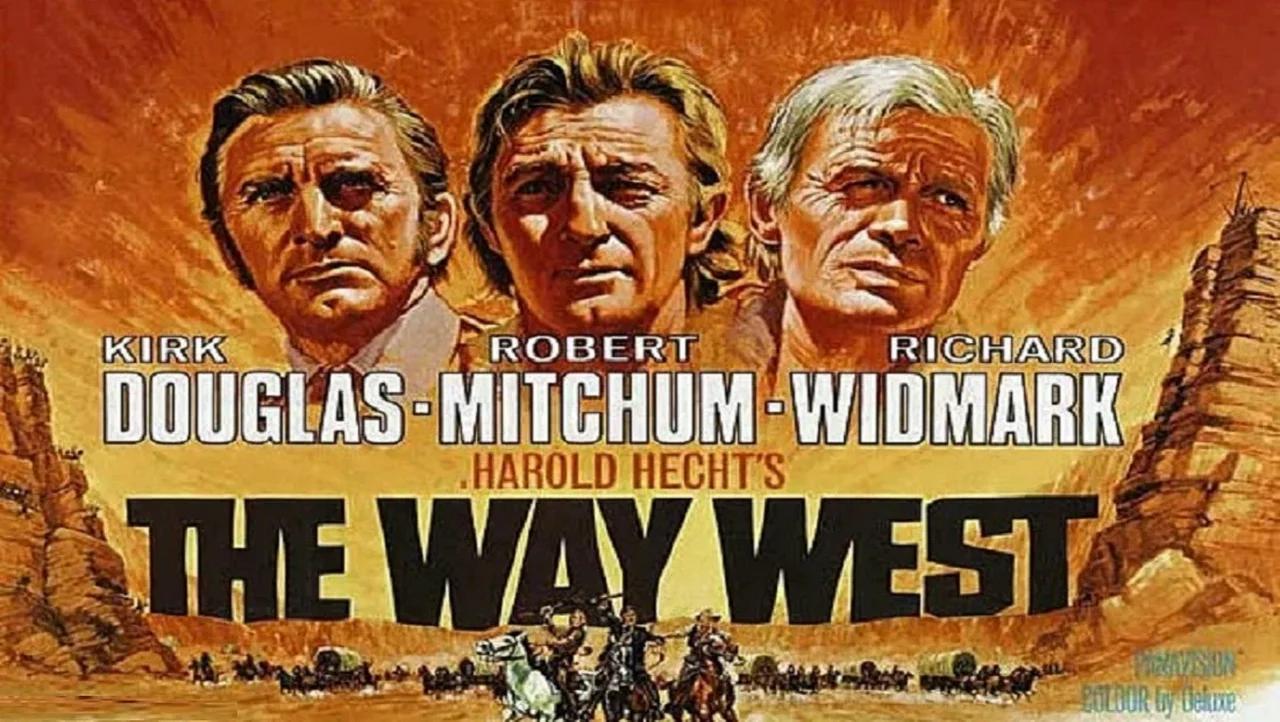

Honestly, if you go back and watch The Way West today, it feels like a fever dream of mid-century Hollywood ambition crashing head-first into the gritty realities of the 1840s. It’s got Kirk Douglas, Robert Mitchum, and Richard Widmark. That's a legendary trio. You'd expect a masterpiece. Instead, what we got in 1967 was a sprawling, beautiful, and occasionally baffling epic that tried to be everything at once. It’s a movie about the Oregon Trail, sure, but it’s also a movie about ego, madness, and the literal weight of a wagon train trying to cross a continent.

It didn't set the world on fire at the box office. People sort of forgot about it compared to The Searchers or True Grit. But for anyone who loves the genre, there is something deeply fascinating about how this film handles the "Westward Ho" mythos.

The Way West and the Burden of the Epic

By the time United Artists put this thing together, the traditional Western was starting to bleed into the Revisionist era. You could feel the change in the air. This wasn't just a story about "cowboys and Indians" anymore. Based on A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, the film focuses on Senator William J. Tadlock (Kirk Douglas), a man so obsessed with founding a new city in Oregon that he treats his fellow travelers like expendable chess pieces.

Douglas is intense. Maybe too intense? He plays Tadlock with a rigid, almost terrifying moral certainty. He wants to build a utopia, but he’s willing to hang a man to maintain discipline. It’s a performance that makes you realize how thin the line was between a "pioneer spirit" and a plain old tyrant.

Why the casting was a double-edged sword

Robert Mitchum plays Dick Summers, the weary scout who’s seen too much. Mitchum, as usual, looks like he’d rather be anywhere else, which actually works perfectly for a character who is grieving his late wife and tired of the trail. Then you have Richard Widmark as Lije Evans, the "common man" who provides the emotional counterweight to Douglas’s fanaticism.

The chemistry is... weird. You have three alpha dogs from the Golden Age of Hollywood all barking in different keys. It’s a heavy-handed dynamic, but it reflects the actual friction of the Oregon Trail. Imagine being stuck in a wooden box for six months with people you can't stand. That’s the real "Way West" experience.

The Production Was a Nightmare (and it shows)

Making The Way West was almost as grueling as the journey it depicted. They filmed on location in Oregon, specifically around Bend and the Deschutes National Forest. Director Andrew V. McLaglen—a protege of John Ford—wanted scale. He got it. But scale costs money and sanity.

🔗 Read more: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

They weren't just using movie props; they were hauling actual wagons across rugged terrain. There’s a scene where they lower wagons down a cliffside using ropes. That wasn't some CGI trick. It was 1967. They were really doing it. You can see the genuine strain on the actors' faces. It’s one of the most visually impressive sequences in Western history, yet it often gets overshadowed by the film’s clunky pacing.

The script went through multiple hands. Ben Maddow and Mitch Lindemann tried to condense Guthrie’s massive book into a two-hour runtime. A lot got lost. Characters appear and disappear. Subplots about a young couple (played by a very young Sally Field in her film debut and Michael Witney) feel like they belong in a different movie.

A Debut to Remember: Sally Field

Let's talk about Sally Field for a second. Before she was an Oscar winner or the Flying Nun, she was Mercy McBee. It’s a strange role. Mercy is a teenager on the trail who gets caught up in a messy, tragic romance that leads to one of the film’s darkest turning points.

Field has since been pretty open about the fact that she didn't really know what she was doing back then. She was just a kid thrown into a cast of giants. But her performance brings a vulnerability that the rest of the movie lacks. While Douglas and Widmark are shouting about destiny, Field is just trying to survive the terrifying social pressures of a mobile community where everyone is watching your every move.

The Problem With the "Indian" Narrative

Look, we have to be real. Like many Westerns of its time, The Way West hasn't aged perfectly in its depiction of Native Americans. It treats the Sioux and other tribes mostly as obstacles or tragic catalysts for the white characters' growth. There’s a plot point involving the accidental killing of a Chief’s son that triggers a standoff. It’s handled with more nuance than a 1940s B-movie, but it’s still firmly rooted in the perspective of the colonizer. If you're watching it through a modern lens, these scenes feel stiff and dated, reminding us how far the genre had to go before movies like Dances with Wolves or Killers of the Flower Moon.

Why Does It Feel So Different From Other Westerns?

The 1960s were a weird time for the genre. You had the hyper-stylized Spaghetti Westerns coming out of Italy and the fading glow of the classic Hollywood Western. The Way West sits awkwardly in the middle. It has the big orchestral score (by Bronisław Kaper) and the wide vistas of an old-school epic, but the tone is surprisingly cynical.

💡 You might also like: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

It’s a movie about failure as much as it is about triumph.

The pioneers lose livestock.

They lose children.

They lose their minds.

There’s a scene where Tadlock forces the group to abandon their sentimental belongings to lighten the load. Pianos, clocks, heirlooms—all dumped in the dirt. It’s a heartbreaking image of what the "American Dream" actually costs. It’s not just hard work; it’s the systematic stripping away of your past.

The Cinematography of William H. Clothier

We have to give credit to William H. Clothier. He was the king of the wide-angle Western. In The Way West, he uses the 2.35:1 Panavision aspect ratio to make the landscape look infinite. The wagons look like tiny ants against the horizon. It’s beautiful. If you can, watch the remastered version on a big screen. The shots of the Columbia River are breathtaking, even if the dialogue occasionally falls flat.

Realism vs. Hollywood Gloss

One of the biggest gripes critics had back in '67 was that the movie couldn't decide if it wanted to be a gritty survival story or a glamorous blockbuster. You'll see a scene where a character dies a gruesome, dusty death, and in the next shot, someone's hair is perfectly coiffed.

The film tries to address the "gross" parts of the trail—the cholera, the thirst, the heat—but then it backs off. It’s "sorta" realistic. It’s "kinda" dark. That hesitation is probably why it didn't become a timeless classic like The Searchers. It lacked a singular, uncompromising vision. McLaglen was a solid director, but he wasn't a poet like Ford or a rebel like Peckinpah.

The Legacy of The Way West

Despite its flaws, the film remains a massive piece of cinema history. It’s a bridge. It’s the end of an era where studios would dump millions of dollars into a "prestige" Western and expect it to be a national event.

It’s also a reminder of the sheer physical power of 60s filmmaking. There are no green screens here. When you see a horse falling into a river, that happened. When you see a storm rolling over the plains, that was the actual weather. There’s a weight to the film that modern digital movies just can't replicate.

📖 Related: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

What You Should Look For on a Re-watch

If you’re going to sit down with The Way West this weekend, pay attention to these three things:

- The Tadlock/Evans Rivalry: Notice how the power shifts. It’s a slow burn. Widmark starts as a follower and ends as the leader. It’s a classic "rise of the common man" arc that actually pays off.

- The Soundscape: The movie uses silence and wind remarkably well. For a big-budget flick, it has moments of quiet that feel incredibly lonely.

- Mitchum’s Eyes: Seriously. Robert Mitchum can act more with a tired squint than most actors can with a five-minute monologue. He’s the soul of the movie.

How to approach the ending (No Spoilers)

The ending is... divisive. Some find it poetic; others find it abrupt. Without giving it away, let’s just say it reinforces the idea that the "West" wasn't won by heroes, but by people who were simply too stubborn to stop walking. It’s a grim, dusty conclusion that leaves a bit of a bitter taste, which is probably the most honest thing about the whole movie.

Digging Deeper into the Oregon Trail

If The Way West sparks an interest in the actual history, there are a few things you should do to get the full picture. The movie gets the "vibe" right, but the history is even crazier.

First, look up the journals of real pioneers. The "Tadlock" type existed, but usually, leadership was more democratic—and more disastrous. Second, check out the geological history of the landmarks mentioned, like Independence Rock. Seeing the actual carvings left by travelers makes the 1967 film feel much more grounded.

Lastly, compare this film to Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. They cover similar ground but in completely opposite universes. One is a singing, dancing fantasy; the other is The Way West. Seeing them back-to-back shows you just how much Hollywood’s idea of the frontier changed in just over a decade.

Your next steps for exploring the genre:

- Watch the 1967 film specifically for the cinematography of William H. Clothier; it’s a masterclass in using the horizon.

- Read the original novel by A.B. Guthrie Jr. to see what the movie left out, especially regarding the internal monologues of the scouts.

- Track down the "making of" anecdotes regarding the tension between Douglas and Mitchum—it adds a whole new layer to their on-screen interactions.

The film isn't perfect, but it’s a massive, dusty, ambitious swing at capturing the American spirit. It’s worth the two hours just to see the wagons go over that cliff.