Ever looked at a ripple in a pond? Or maybe you've wondered why your Wi-Fi signal drops the moment you step behind a thick brick wall? It’s all down to one specific measurement. Basically, the wavelength of a wave is the physical distance between two consecutive peaks—or troughs—of that wave. It sounds simple. It’s not.

Most people think of waves as just these abstract lines on a graph in a dusty physics textbook. But waves are everywhere. They are the light hitting your eyes right now. They are the heat warming your coffee. They are the invisible signals carrying this article to your screen. If you change the wavelength, you change the world. You turn blue light into red light. You turn a lethal X-ray into a harmless radio broadcast.

What exactly are we measuring?

When we talk about the wavelength of a wave is being a "distance," we mean it literally. If you could freeze time and lay a ruler down on a beam of light, the wavelength would be the space from one "crest" (the high point) to the next. In the world of physics, we usually label this with the Greek letter lambda, written as $\lambda$.

It’s easy to visualize with water. You see a wave coming in at the beach. You see the next one right behind it. The distance between those two salty peaks? That’s the wavelength. In a vacuum, light travels at a constant speed—about 300,000 kilometers per second. Because that speed doesn't change, the wavelength and the frequency (how fast the wave vibrates) have this tight, unbreakable relationship. If the wavelength gets shorter, the frequency must go up. It’s a seesaw. One goes up, the other goes down.

Why your microwave and your cell phone don't kill you

This is where things get interesting. The electromagnetic spectrum is a massive range of wavelengths. On one end, you have radio waves. These things are huge. Some radio wavelengths are literally kilometers long. They can pass through buildings and mountains because they’re so stretched out.

On the flip side, you have Gamma rays. Their wavelengths are smaller than the nucleus of an atom. Because they are so incredibly "tight" and vibrating so fast, they carry massive amounts of energy. This is why you can stand in front of a radio tower all day and be fine, but a few seconds of raw Gamma radiation will scramble your DNA.

✨ Don't miss: iPhone 16 Pro Natural Titanium: What the Reviewers Missed About This Finish

The wavelength of a wave is what determines its personality.

Consider the microwave in your kitchen. It uses a wavelength of roughly 12 centimeters. This specific length is perfect because it happens to be great at jiggling water molecules. When those molecules jiggle, they create friction. Friction creates heat. Your burrito gets hot. If that wavelength were just a few centimeters different, your lunch would stay frozen. It’s that precise.

The color of the world is just a measurement

Visible light is just a tiny, tiny sliver of the spectrum. Humans can only see wavelengths between roughly 380 and 700 nanometers. A nanometer is a billionth of a meter. It’s tiny.

- Violet sits at the short end (around 400 nm).

- Red sits at the long end (around 700 nm).

Everything else—every sunset, every painting, every blade of grass—is just your brain interpreting different wavelengths of light bouncing off objects. Honestly, color isn't "real" in a physical sense; it’s just how our eyes sort out the different sizes of the waves hitting them. If you’ve ever used a prism, you’ve seen this in action. The prism slows down the light, and because different wavelengths bend at different angles, the white light "breaks" into its component colors. Short wavelengths (blue/violet) bend more than long wavelengths (red).

Sound waves are the weird cousins

Light waves are "transverse" waves. They wiggle up and down. But sound? Sound is a "longitudinal" wave. It’s more like a Slinky being pushed and pulled. The wavelength of a wave is still measured the same way—from the center of one compression (where the air molecules are smashed together) to the next.

🔗 Read more: Heavy Aircraft Integrated Avionics: Why the Cockpit is Becoming a Giant Smartphone

Ever wonder why you can hear the bass from a neighbor's party but not the lyrics? It’s wavelength again. Deep, low-pitched sounds have long wavelengths. They can wrap around corners and travel through walls. High-pitched sounds have tiny wavelengths that get absorbed or bounced off by almost any obstacle. If you want to soundproof a room, you’re mostly fighting the long wavelengths because they are the hardest to stop.

The math that keeps the internet running

In the world of fiber optics, we use light to send data. But we don't just use any light. Engineers specifically choose wavelengths that can travel long distances through glass fibers without losing strength. Usually, this is in the infrared range, around 1,550 nanometers.

At this specific "window," the glass is most transparent. If we used a different wavelength, the signal would fade out after a few miles. Because we found the "sweet spot" wavelength, we can send gigabytes of data across the ocean in milliseconds.

Mistakes people make with wave theory

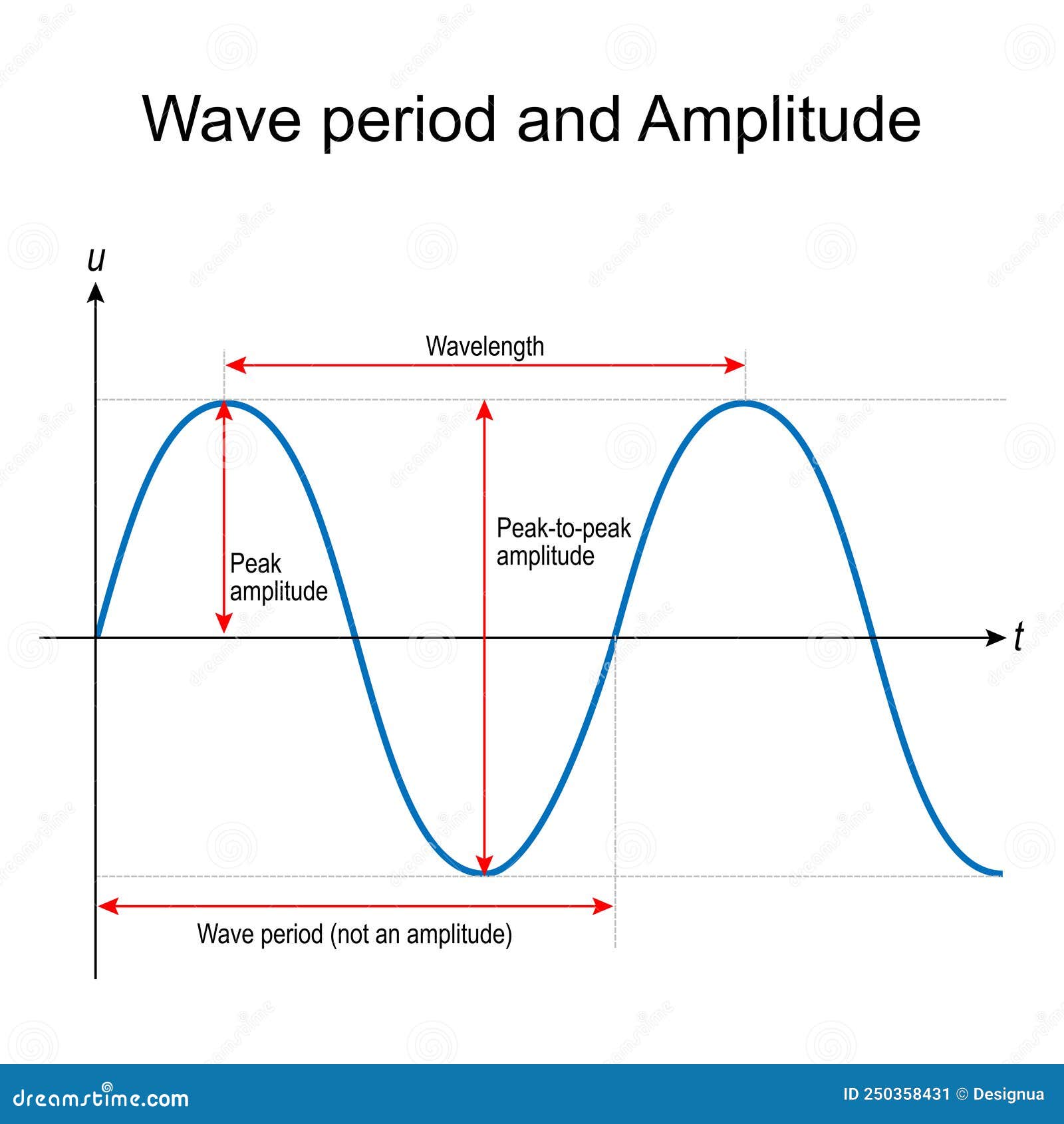

People often confuse wavelength with amplitude. Amplitude is the height of the wave. In sound, amplitude is volume. In light, it's brightness.

Changing the amplitude doesn't change the color or the pitch; it just makes it "more." Imagine a wave in the ocean. A tall wave and a short wave can have the exact same wavelength (the distance between them), but one will knock you over while the other just wets your toes.

💡 You might also like: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

Another common mix-up? Thinking that waves need a "medium" to travel. Sound does—it needs air, water, or solid ground. But light? Light is a rebel. It doesn't need anything. It travels through the vacuum of space. The wavelength of a wave is still there, even in the nothingness of the void between stars. This is how astronomers like those at the James Webb Space Telescope can tell what a star is made of. They look at the "spectral lines"—specific wavelengths of light that are missing because they were absorbed by gases around the star. Every element, like Hydrogen or Helium, has its own "wavelength fingerprint."

How to use this knowledge in the real world

Understanding that the wavelength of a wave is a physical, tangible thing helps you solve everyday problems.

- Wi-Fi Placement: Most Wi-Fi runs on 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz. The 2.4 GHz waves are longer. This means they are better at going through walls. If you’re two rooms away from your router, 2.4 GHz will actually give you a more stable connection than the "faster" 5 GHz, because the 5 GHz wavelengths are too short to navigate the obstacles.

- Photography: Ever wonder why the sky is blue but sunsets are red? It’s called Rayleigh scattering. Small gas molecules in the atmosphere scatter shorter wavelengths (blue) more easily. During sunset, the light has to travel through much more atmosphere to reach you. The blue is all scattered away, leaving only the long, stubborn red wavelengths to reach your eyes.

- Noise Cancellation: High-end headphones don't just "block" sound. They have a microphone that listens to the incoming sound wave and then generates a "mirror" wave with the exact same wavelength but inverted. The peaks of the noise meet the troughs of the "anti-noise," and they cancel each other out. Total silence through math.

The future of "Wavelength Engineering"

We are currently pushing the boundaries of what we can do with wave manipulation. Scientists are working on "metamaterials" that can bend light in ways that don't occur in nature. The goal? To create a literal "invisibility cloak" by bending the wavelengths of light around an object so they come out the other side as if the object wasn't even there.

It sounds like sci-fi, but it’s just advanced geometry involving the wavelength of a wave is and how it interacts with microscopic structures.

Practical Next Steps

- Audit your home tech: Check your router settings. If you have a "dead zone" in your house, force that device to use the 2.4 GHz band. Those longer wavelengths will handle the drywall much better than the high-frequency bands.

- Protect your eyes: If you spend all day on a computer, look into the "blue light" debate. While the jury is still out on permanent damage, shorter wavelengths (blue light) carry more energy and are known to disrupt circadian rhythms. Use a filter to shift your screen toward the longer, redder end of the spectrum in the evening.

- Observe the world: Next time you see a rainbow or a peacock feather, remember you aren't seeing "stuff." You are seeing a physical interaction where the wavelength of a wave is being sorted, bent, or reflected in a very specific way.