Six billion kilometers. It’s a distance so vast the human brain basically shorts out trying to visualize it. But in 1990, a small, boxy machine powered by decaying plutonium turned its camera lens back toward home and captured what we now call the Voyager 1 picture of Earth.

You’ve seen it. Or you think you have. It’s that grainy, noise-streaked image where our entire world is reduced to a single pixel, suspended in a beam of scattered sunlight. It’s officially titled "Pale Blue Dot." Honestly, it’s one of the most humbling things humans have ever produced.

The story of how we got that photo isn't just about math and physics. It was a fight. NASA didn't really want to take it. The mission was technically over. Voyager 1 had already zipped past Jupiter and Saturn. It was heading into the dark, empty nothingness of interstellar space. Turning the cameras around posed a risk to the instruments, and some engineers thought it was a waste of precious resources.

Carl Sagan didn't care. He pushed. He knew that seeing ourselves from that far away would change how we think about everything. He was right.

The Drama Behind the Pale Blue Dot

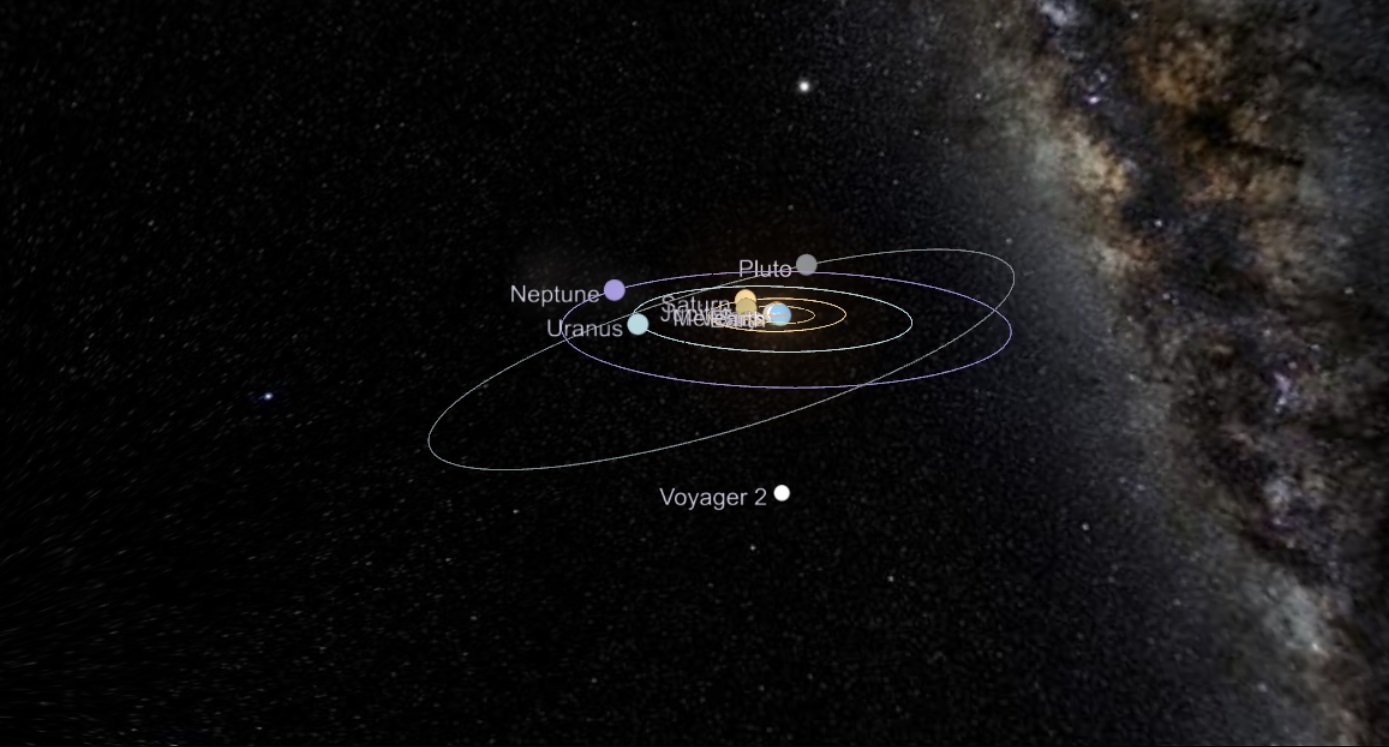

The Voyager 1 picture of Earth almost never happened. By 1990, Voyager 1 was high above the ecliptic plane—the flat "disk" where most planets orbit the sun. It had a literal bird's-eye view of the solar system. Sagan had been campaigning for this "family portrait" of the planets since the late 70s.

NASA leadership was hesitant.

👉 See also: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

The main concern? The sun. Pointing a sensitive camera back toward the inner solar system meant risking the imaging tubes. If the sun’s light hit them directly, they’d be fried. It wasn't until Richard Truly, the NASA Administrator at the time, stepped in that the command was finally sent.

On February 14, 1990, the spacecraft snapped 60 frames.

It took months for the data to trickle back to Earth. Radio signals traveling at the speed of light still take hours to bridge that gap. When the image finally arrived, it wasn't a high-definition masterpiece. It was messy. The "beam" of light crossing Earth is actually just an optical artifact—sunlight scattering inside the camera lens because of the tight angle. Earth just happened to be sitting right in the middle of one of those rays.

Pure luck.

What the Voyager 1 Picture of Earth Actually Shows

If you look at the raw file, Earth is barely there. It’s 0.12 pixels in size.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

People often mistake the streaks of light for something cosmic, like a nebula or a solar flare. Nope. It’s just glare. But that glare provides the perfect frame. It makes the Earth look like a tiny, fragile speck of dust caught in a sunbeam.

Why the quality is so low

Voyager used 1970s technology. We’re talking about vidicon cameras that recorded images onto a digital tape recorder before beaming them back via a 3.7-meter high-gain antenna. The resolution is 800 by 800 pixels. Compared to the camera in your pocket right now, it’s prehistoric. Yet, no iPhone photo will ever carry the same weight.

The "Family Portrait" series

While the Voyager 1 picture of Earth gets all the glory, it was actually part of a larger mosaic. The spacecraft captured Neptune, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, and the Sun. Mars was lost in the sun's glare. Mercury was too close to the sun to see. Pluto was too faint.

It’s a lonely image.

The Science of Interstellar Photography

Taking a photo from 3.7 billion miles away isn't like pointing and clicking. Voyager 1 was moving at about 40,000 miles per hour. To get a clear shot, the spacecraft had to be incredibly stable.

🔗 Read more: robinhood swe intern interview process: What Most People Get Wrong

The "Pale Blue Dot" was taken through three different filters: blue, green, and violet. Scientists then recombined these to create the color image we see today. The fact that Earth appears blue isn't an accident or an edit; it’s the actual Rayleigh scattering of our atmosphere, even from that distance.

In 2020, for the 30th anniversary, NASA JPL processed the image again using modern software. They cleaned up the "noise" and adjusted the levels, making the dot pop just a bit more against the darkness. It’s clearer, but the feeling remains the same: we are very, very small.

Common Misconceptions About the Image

- "It was taken from the edge of the galaxy." Not even close. Voyager 1 was still inside our solar system. The galaxy is roughly 100,000 light-years across. Voyager was only about 5.5 light-hours away.

- "You can see the continents." Impossible. Earth is smaller than a single grain of salt in that photo. You're seeing the combined light of the entire planet.

- "Voyager 1 is still taking photos." No. To save power and memory for the instruments that measure plasma and magnetic fields, the cameras were turned off shortly after the Family Portrait was completed. The software to run the cameras was even removed from the flight computer to make room for other things.

The Legacy of a Single Pixel

The Voyager 1 picture of Earth changed environmentalism and philosophy. It provided the "Overview Effect" to people who would never go to space. It showed that there is no help coming from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

We’re on a raft in a very big ocean.

Sagan’s famous speech about the "Pale Blue Dot" is often quoted, but the core of it is simple: it’s a challenge to our ego. Every king, every peasant, every "superstar" and corrupt politician lived out their entire lives on that tiny speck. It makes our local conflicts look pretty ridiculous.

How to Experience the Voyager Legacy Today

If you're fascinated by this, you don't have to just look at a grainy JPG. There are ways to engage with the mission as it happens.

- Check the Real-Time Stats: NASA has a "Eyes on the Solar System" tool that shows exactly where Voyager 1 is right now. It’s currently over 15 billion miles away.

- The Golden Record: Voyager carries a copper phonograph record with sounds and images of Earth. You can listen to the tracks on SoundCloud or YouTube. It’s the ultimate "message in a bottle."

- Read "Pale Blue Dot": Carl Sagan’s book of the same name expands on the philosophy behind the photo. It’s arguably more relevant now than it was in 1994.

Actionable Steps for Space Enthusiasts

- Download the High-Res 2020 Remaster: Don't settle for the blurry 1990 version. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) website hosts the reprocessed version which is much better for prints or wallpapers.

- Use NASA's "Deep Space Network Now": This is a cool web tool that shows which giant antennas on Earth are currently talking to which spacecraft. You can often see "VGR1" or "VGR2" listed when they are downloading data.

- Support Light Pollution Reduction: To see the stars that Voyager is currently flying toward, we need dark skies. Look up the International Dark-Sky Association to find a "Dark Sky Park" near you. Seeing the Milky Way with your own eyes puts the Voyager 1 picture of Earth into a physical context that a screen just can't match.

The cameras on Voyager 1 are cold and dead now. They haven't clicked in over three decades. But the data they sent back—that specific arrangement of pixels—remains the most important selfie ever taken. It’s a reminder that our world is small, rare, and the only one we’ve got.