Walk into any dusty roadside motel in the Southwest or a basement bar that hasn't been renovated since 1974, and you might see him. The King. He’s glowing. Not because of some divine intervention, but because his pompadour is rendered in thick, oil-slicked paint on a background of deep, light-absorbing black velvet. People laugh at a velvet painting of Elvis. It’s the ultimate punchline for "bad taste." But honestly? That’s a massive oversimplification of an art form that actually has roots in 14th-century Kashmir and once represented a billion-dollar industry.

It’s weird. It’s fuzzy. It’s undeniably American, even if the vast majority of these portraits were actually painted in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

Most people think of the velvet Elvis as a relic of the "cheesy" seventies. But if you look closer, there’s a reason this specific medium became the vessel for the Presley mythos. The black velvet acts as a total light sink. It absorbs everything around it, which makes the highlights—the shimmering gold of a jumpsuit, the sweat on a brow, the glint in a curled lip—pop with a literal, physical intensity that canvas just can't replicate. It’s high-contrast drama. It’s neon in a coal mine.

The Juárez Connection and the Birth of an Icon

The story of the velvet painting of Elvis isn't really a story about Memphis. It’s a story about the border. In the late 1960s and throughout the 70s, Ciudad Juárez became the global capital of velvet art. It wasn't just a few hobbyists; we're talking about massive studios where artists like Doyle Harden employed hundreds of painters to churn out thousands of pieces a week.

Harden is a name you should know if you care about this stuff. He was an American entrepreneur who realized that the "starving artist" trope could be turned into a factory model. He didn't invent the medium—that credit often goes to Edgar Leeteg, who painted Tahitian scenes on velvet in the 30s—but Harden industrialized it. His workers would line up dozens of velvet sheets. One person would paint the sky. The next would do the eyes. The next would handle the signature.

👉 See also: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

It was an assembly line of soul.

And Elvis was the top seller. Why? Because Elvis was the secular saint of the working class. When he died in 1977, the demand for a velvet painting of Elvis didn't just grow—it exploded. People wanted a shrine. They wanted something that looked like it belonged in a cathedral but felt at home next to a wood-paneled Philco television. The velvet provided a texture that felt expensive to people who couldn't afford "fine art," but more importantly, it felt emotional.

Why Velvet Works (And Why We Secretly Love It)

Let’s talk about the physics of the thing. Black velvet is a "non-reflective" surface. When you put paint on it, the pigment sits on top of the fibers rather than soaking into a weave. This creates a 3D effect. In the context of Elvis, this was perfect. It captured his "Vegas period" better than any other medium. The rhinestones on his cape actually seem to sparkle when you walk past the painting because the light hits the raised paint while the velvet background stays pitch black.

It’s tactile.

✨ Don't miss: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

You’re not supposed to touch art, right? But you want to touch velvet. There is a "forbidden" quality to it. It’s low-brow, sure, but it’s also incredibly sincere. There is no irony in a velvet painting of Elvis created in 1978. The artist wasn't trying to be "meta." They were trying to capture a god.

Interestingly, the art world has spent decades trying to figure out where to put these things. Is it folk art? Is it commercial kitsch? Is it "outsider art"? Critics like Dave Hickey, who wrote famously about Las Vegas and the aesthetics of pleasure, argued that this kind of art is more honest than the stuff hanging in the MoMA. It’s art that people actually want to live with. It’s art that serves a purpose: grief, celebration, or just filling a void on a beige wall with a burst of indigo and silver.

The Different Faces of the King

If you start hunting for these at estate sales or on eBay, you'll notice three distinct "archetypes" of the velvet painting of Elvis:

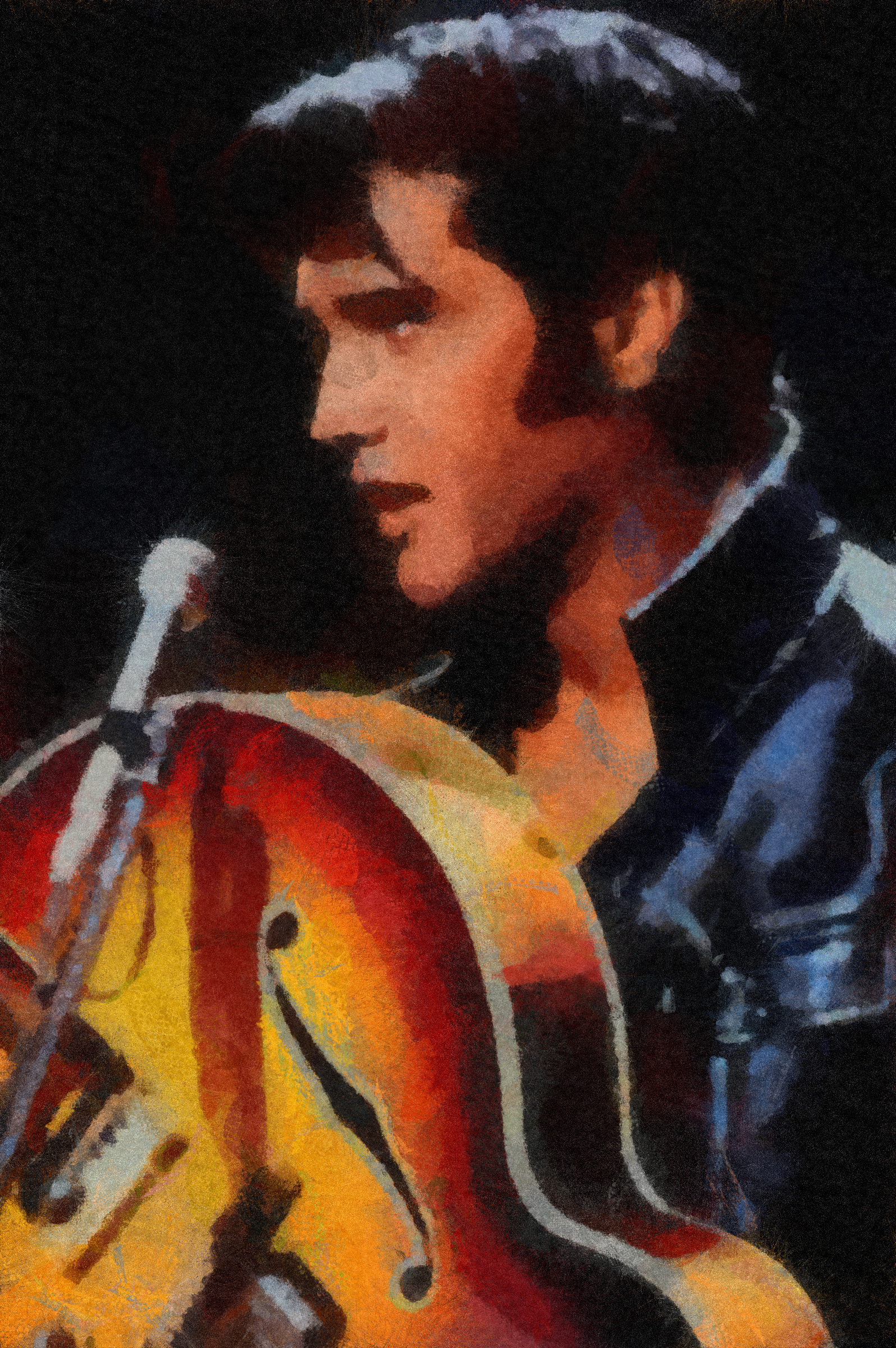

- The Young Rebel: Usually 1950s era. High-contrast black hair, a hint of a sneer, maybe a guitar. These are rarer because the velvet craze really peaked during his later years.

- The 1968 Comeback: Leather suit, brooding eyes. These are the "cool" ones that serious collectors hunt for.

- The Aloha from Hawaii/Vegas King: The heavy hitter. White jumpsuit, massive sideburns, sweat, and glory. This is the definitive velvet Elvis.

The Valuation of "Trash"

You might find a mass-produced version for $20 at a flea market. However, "signed" pieces from the major Juárez studios or early Leeteg-style works can actually fetch hundreds, sometimes thousands of dollars. The Velveteria, a museum formerly in Portland and later Los Angeles (run by Caren Anderson and Carl Baldwin), helped legitimize the medium by showing the sheer technical skill required to paint on a surface that "fights" the brush.

🔗 Read more: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

You can't erase on velvet. One mistake and the piece is ruined. The paint has to be applied with a dry brush technique or it will clump and look like mud. It takes a steady hand and a weirdly specific understanding of how light interacts with fabric.

Where to Find and How to Care for Velvet Art

If you’re looking to buy a velvet painting of Elvis, don’t look at traditional galleries. You want the "In Search of" sections of Craigslist, small-town antique malls, or specialized online auctions. But beware of "new" velvet. Modern versions often use synthetic velvet that looks shiny and cheap. The vintage stuff uses a cotton-based velvet that has a much deeper, matte "void" effect.

Cleaning them is a nightmare. Do not use water. Do not use Windex. You basically have to use a very soft brush or a light puff of air to get the dust out of the fibers. They are magnets for pet hair and cigarette smoke—which, honestly, is part of the authentic patina for many of these pieces.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Collector

If you're ready to embrace the kitsch, here is how you handle your first foray into the world of velvet royalty:

- Check the Backing: Authentic vintage pieces from the 60s and 70s are usually stretched over hand-made wooden frames, often with rough-hewn slats. If it's on a modern, machine-cut frame, it’s likely a reproduction.

- Study the Eyes: The quality of a velvet painting of Elvis lives and dies in the eyes. In mass-produced "zombie" versions, the eyes look flat. In high-quality studio pieces, the eyes have a "follow-me" quality created by layered white highlights.

- Sniff Test: It sounds gross, but vintage velvet art often carries the scent of its previous home. If it smells like a 1970s bowling alley, you’ve found the real deal. That’s history.

- Lighting is Key: Never hang a velvet painting under direct overhead fluorescent light. It kills the effect. These pieces were designed for "mood lighting"—think low-wattage lamps or even a dedicated picture light that grazes the surface from an angle. This makes the texture of the paint stand out against the abyss of the velvet.

- Identify the Artist: Look for names like "Goetz" or "Romo" in the corners. While many were unsigned, certain artists from the Juárez era have developed their own "blue chip" status in the kitsch world.

The velvet painting of Elvis isn't just a joke. It’s a testament to a time when art was tactile, unapologetic, and deeply connected to the people. It’s a bit of velvet-wrapped stardust that refuses to fade away. Whether you find it beautiful or hideous, you have to admit: it’s hard to look away.