Steel. Firepower. Digital brains. When people think of the Navy, they usually picture the massive aircraft carriers—those floating cities that dominate the horizon. But if you talk to anyone who’s actually spent time in the Pentagon or on a bridge at sea, they’ll tell you the real workhorse is the USN guided missile destroyer. It’s the knife in the dark. It’s the shield for the fleet. Honestly, without these ships, those fancy carriers would basically be sitting ducks.

The Arleigh Burke-class is the name you’ll hear most often. It’s the backbone. Since the USS Arleigh Burke (DDG 51) was commissioned way back in 1991, the design has been tweaked, stretched, and overhauled so many times it’s barely the same ship anymore. We’ve gone from Flight I all the way to the newest Flight III models. It’s a bit like taking a classic truck and constantly swapping the engine and sensors until it can outrun a Ferrari. These ships are designed to hunt submarines, swat down incoming missiles, and strike targets hundreds of miles inland. They do it all.

What makes a USN guided missile destroyer so lethal?

It isn't just the guns. In fact, the 5-inch gun on the bow is almost secondary these days. The real "magic" happens inside the Vertical Launch System (VLS) cells. Think of these as a massive honeycomb of missile tubes buried in the deck. Depending on the mission, a commander can pack these tubes with Tomahawk cruise missiles for land attacks, SM-6 missiles for high-end air defense, or even the RUM-139 VL-ASROC for killing subs.

💡 You might also like: Why That Apple Fraud Phone Number In Your Inbox Is Probably A Trap

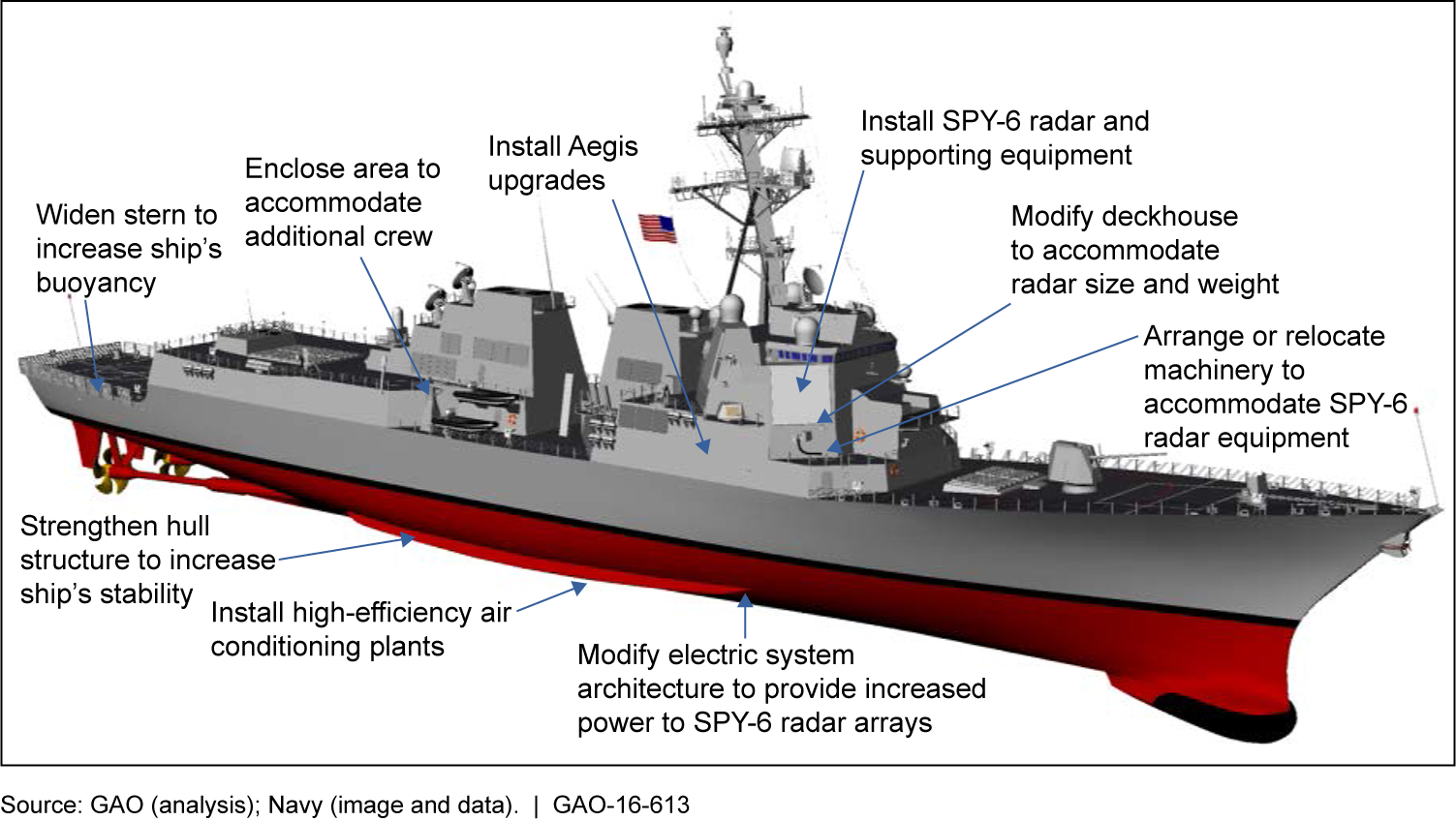

The heart of the ship is the Aegis Weapon System. It’s a massive integration of radar and computing power that can track over a hundred targets simultaneously. The SPY-1 radar arrays—those flat octagons you see on the superstructure—are iconic. However, on the newest Flight III ships, the Navy is moving to the SPY-6 Air and Missile Defense Radar (AMDR). It is significantly more sensitive. We’re talking about the ability to see smaller objects, further away, with much better clarity. This is crucial because threats are getting faster. Hypersonic missiles aren't a "maybe" anymore; they're a reality that these ships have to face.

The Zumwalt-class (DDG 1000) was supposed to be the future. It looks like something out of a sci-fi movie with its tumblehome hull and stealthy angles. But, honestly, it’s been a bit of a rocky road. The Navy only built three of them. The Advanced Gun System they designed for it became too expensive to buy ammo for, so now they’re looking at repurposing those ships to carry Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) hypersonic missiles. It’s a pivot. Sometimes the "bleeding edge" of technology actually bleeds.

The crew reality: Life on a DDG

Living on a destroyer is cramped. It’s loud. You’re on a ship that’s about 510 feet long with roughly 300 other people. Unlike a carrier, which feels like a city, a destroyer feels like a community. Or a very crowded hallway. You feel every wave. When the ship is "darkened down" for night ops, the red lights give everything a surreal, tense vibe.

✨ Don't miss: 2023 GMC Hummer EV Pickup: What Most People Get Wrong

The workload is staggering. Maintaining a USN guided missile destroyer means constant chipping of paint, testing electronics, and "cleaning stations" until your hands are raw. But there’s a pride in it. Destroyer sailors call themselves "Tin Can Sailors," a nickname that sticks even though modern ships are made of high-strength steel, not tin. They know they’re the ones on the front lines of freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea or intercepting Houthi drones in the Red Sea.

The move toward the DDG(X)

The Navy knows the Arleigh Burke hull is reaching its physical limit. You can only add so much weight and draw so much power before the ship becomes unstable or runs out of "juice" for new lasers and sensors. That’s where the DDG(X) comes in. It’s the next-generation program.

The goal for DDG(X) isn't just more missiles. It’s about power. We are talking about Directed Energy weapons—lasers. To fire a high-power laser and take out a drone, you need a massive amount of instantaneous electrical power. The current Burkes struggle with that. The DDG(X) will likely use an Integrated Power System similar to the Zumwalt, allowing the ship to shift power from the engines to the weapons systems in a heartbeat.

📖 Related: Walmart Cell Phone Plan Deals: What Most People Get Wrong

- AN/SPY-6(V)1 Radar: The new standard for sensing.

- Baseline 10 Aegis: The software "brain" that coordinates everything.

- SEWIP Block 3: Electronic warfare tools that can jam enemy seekers without firing a single shot.

- HELIOS: A literal laser being tested for short-range defense.

The evolution is constant. If you look at the USS Jack H. Lucas (DDG 125), the first Flight III, it looks familiar but the internal "nervous system" is completely redesigned. It has to be. The Pacific is a big place, and the potential for a high-end conflict requires sensors that can see over the horizon and talk to satellites and F-35s in real-time.

Why people get the "Stealth" thing wrong

There’s a common misconception that every new USN guided missile destroyer should be invisible. People see the Zumwalt and think that’s the goal for everything. It’s not. Total stealth is incredibly expensive and often requires trade-offs in terms of how many weapons you can carry or how easy the ship is to maintain.

The Arleigh Burkes use "stealthy features"—angled surfaces to reduce radar cross-section—but they aren't "stealth ships." They rely on Electronic Warfare (EW) and decoys. Why try to be invisible when you can just make the enemy's radar see fifty ghost ships instead of one? The Nulka active decoy is a great example. It’s a hovering rocket that mimics the ship’s electronic signature to lure missiles away. It’s clever. It’s cheaper than building a whole ship out of exotic composites.

Looking at the numbers and the geopolitics

The US currently operates over 70 Arleigh Burke destroyers. That’s a massive fleet. By comparison, China’s Type 052D and Type 055 destroyers are catching up in terms of raw numbers and sensor capability. This isn't a game of "who has the most." It’s a game of "who can survive the first 15 minutes of a fight."

The cost of a single new Flight III destroyer is roughly $2 billion. That sounds like a lot—because it is. But when you consider that this ship is expected to protect a $13 billion aircraft carrier and its 5,000 crew members, the math starts to make sense. It’s an insurance policy that happens to carry enough firepower to level a small city.

Naval analysts like Bryan Clark have often pointed out that the Navy’s reliance on these expensive, multi-mission ships might be a vulnerability. If you lose one, you lose a huge chunk of your capability. There’s a push now for "Distributed Maritime Operations." This basically means spreading the sensors and weapons across more, smaller platforms—maybe even unmanned ones. But for now, the destroyer remains the king of the chessboard.

Actionable Insights for the Future of Naval Tech

Understanding the trajectory of the USN guided missile destroyer isn't just for history buffs. It’s a window into how global power is shifting. If you're tracking this space, keep an eye on these specific developments:

- Watch the VLS count. As China launches ships with 112 cells (Type 055), see how the US responds with the DDG(X) design. Capacity matters in a "magazine depth" fight.

- Monitor the "Great Laser Race." The first ship to successfully integrate a 300kW+ laser will change the cost-exchange ratio of missile defense forever. Shooting a $10 electricity "bullet" at a $100,000 drone is a win.

- Check the maintenance backlogs. A ship is only a threat if it’s at sea. The biggest weakness of the US destroyer fleet right now isn't the technology; it's the lack of drydock space to keep them repaired.

- Follow the sensor fusion. The real winner of future naval battles won't have the biggest gun; they'll have the best "Common Operational Picture." Look for updates on Project Overmatch.

The destroyer isn't going anywhere. It’s changing, sure. It’s getting more digital, more power-hungry, and more expensive. But at the end of the day, when things go south in some distant corner of the ocean, the USN guided missile destroyer is the first thing the President asks for. It’s the ultimate "don't mess with me" signal.

To stay ahead of the curve, focus on the transition from the Arleigh Burke Flight III to the DDG(X) prototypes. That transition will define the next forty years of maritime security. Pay attention to the shipyards in Maine (Bath Iron Works) and Mississippi (Ingalls Shipbuilding)—that’s where the future is being welded together, one steel plate at a time.