Walk into any coffee shop in early November and you’ll hear the same exhausted refrain: "Why do we only have two choices?" It feels like a glitch in the matrix. We have 50 brands of cereal and 700 streaming services, yet when it comes to the people running the nuclear codes, it’s basically just Red vs. Blue. Most people think it’s a conspiracy or some weird law written by the Founding Fathers to keep power in a tight circle.

Honestly? It's not.

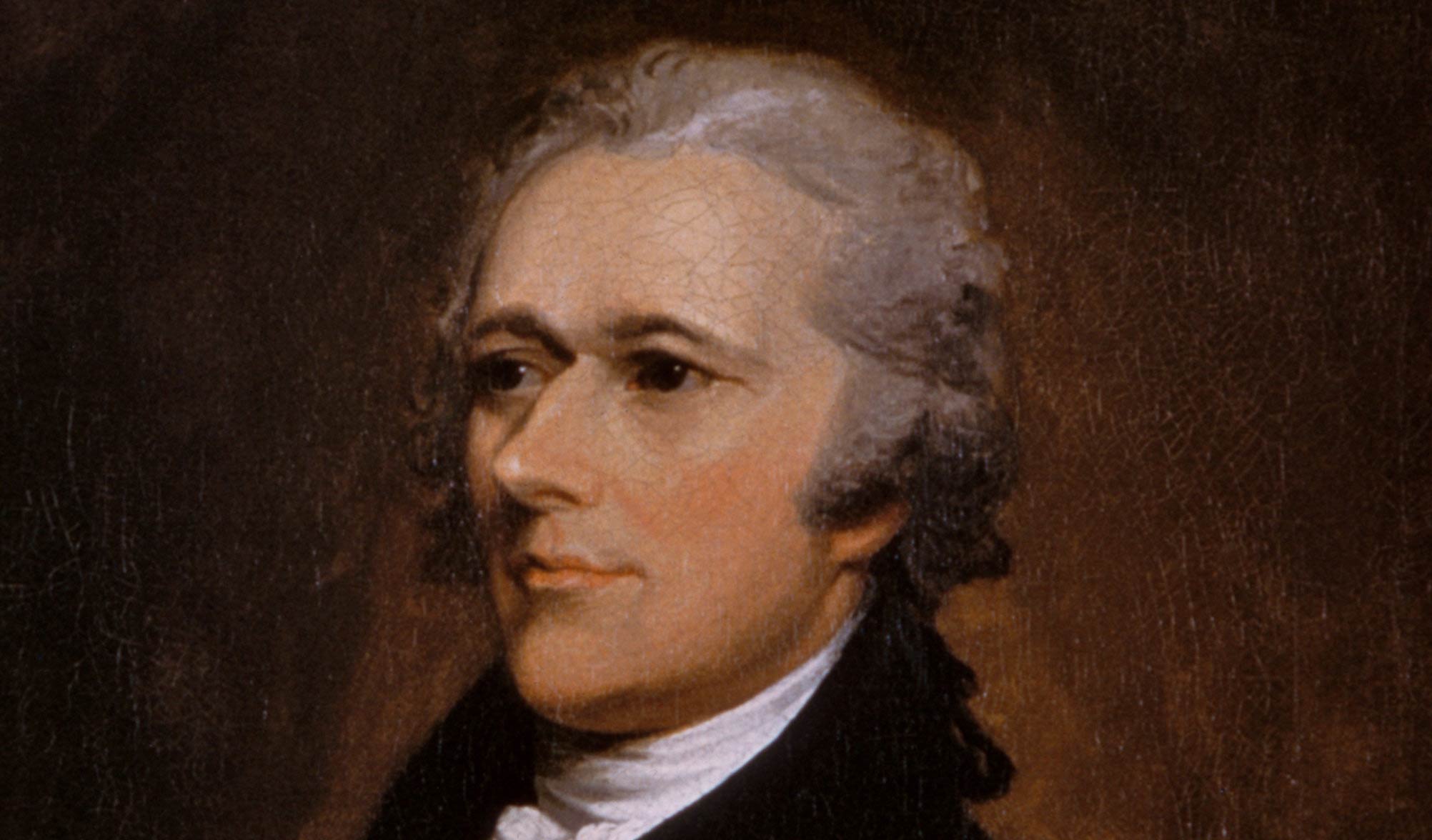

The reason why the United States has a two party system isn't actually written in the Constitution. In fact, George Washington famously hated the idea of parties. He thought they would be "frightful despotism." But we ended up here anyway because of math. Specifically, a quirky little concept called Duverger’s Law. If you want to understand why your third-party vote feels like a "waste" to your neighbors, you have to look at the plumbing of our elections.

The Math of Why the United States Has a Two Party System

Most of our elections are "winner-take-all." In political science speak, we call this Single-Member District Plurality (SMDP). It’s basically the "Talladega Nights" of politics: if you ain’t first, you’re last.

Imagine a three-way race in a fictional district. Candidate A gets 34% of the vote. Candidate B gets 33%. Candidate C gets 33%. In many other countries—places like Germany or New Zealand—those 33% chunks would actually mean something. They’d get seats in parliament. But in the U.S.? Candidate A wins everything. The other 66% of voters get zero representation.

Over time, voters get smart. Or cynical. They realize that if they vote for a third-party candidate they actually like, they might accidentally help the candidate they hate the most by splitting the vote. This is the "spoiler effect." Remember Ralph Nader in 2000? Or Ross Perot in 1992? Whether they actually "spoiled" those elections is a massive debate among data nerds like Nate Silver, but the fear of it is what keeps the two-party engine humming. Voters consolidate into two big tents just to make sure the "other guy" doesn't win. It’s defensive voting.

The Founding Fathers Actually Warned Us

It’s kinda hilarious that we have this rigid system when the guys who started the country were terrified of it. James Madison wrote about "factions" in Federalist No. 10. He hoped that a large republic would have so many different interests that no single group could take over.

✨ Don't miss: Melissa Calhoun Satellite High Teacher Dismissal: What Really Happened

He was wrong.

By the time John Adams was in office, the lines were already drawn between the Federalists (who liked a strong central government) and the Democratic-Republicans (who were more about states' rights). We’ve had different names since then—Whigs, Federalists, National Republicans—but the binary structure stayed. It’s like a biological niche that can only hold two apex predators at a time.

Why Third Parties Usually Crash and Burn

People love to talk about the Libertarians or the Green Party. They have passionate followers. But they hit a brick wall every four years.

First, there’s the ballot access problem. Each state has its own rules for how you even get your name on the piece of paper. In some places, you need tens of thousands of signatures just to be considered. The big two parties? They’re already there. They wrote the rules.

Then there’s the money. The Commission on Presidential Debates has historically required candidates to poll at 15% nationally to get on the stage. How do you get to 15% if nobody knows who you are because you aren't on the stage? It’s a classic Catch-22.

The "Big Tent" Strategy

One reason why the United States has a two party system that actually lasts is that our parties are incredibly stretchy. In Europe, if you have a specific niche interest—say, extreme environmentalism—you start a "Green Party." In the U.S., you just try to take over the Democratic Party from the inside.

🔗 Read more: Wisconsin Judicial Elections 2025: Why This Race Broke Every Record

Think about the Republican Party. It currently holds libertarians, evangelical Christians, and blue-collar populists. Those groups don't agree on everything. Not even close. But they’ve realized that it’s more effective to bicker inside the tent than to stand outside in the rain.

The parties act like giant sponges. When a third party starts getting traction—like the Populist Party in the late 1800s—one of the two big parties usually just "eats" their best ideas. They absorb the momentum, and the third party disappears. It's ruthless, but it's how the system survives.

Regionalism and the Electoral College

We can't talk about this without mentioning the Electoral College. Since almost every state (except Maine and Nebraska) awards all their electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote in that state, there is zero incentive for a third party to finish second or third.

If a candidate gets 20% of the vote across the entire country but doesn't win a single state, they get zero electoral votes. It’s brutal. It makes it mathematically impossible for a new party to rise up unless a major party literally collapses—which has only happened a couple of times in American history, like when the Whigs imploded over the issue of slavery in the 1850s.

Is This System Actually Bad?

Depends on who you ask.

Critics say it leads to polarization. If you only have two sides, everything becomes a "us vs. them" battle. There’s no room for nuance or "third way" solutions. It makes people feel like their vote doesn't matter if they don't live in a swing state.

💡 You might also like: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

On the flip side, some political scientists argue it provides stability. In multi-party systems, you often see "coalition governments" that can fall apart in a week if one small party gets grumpy and leaves. The U.S. system forces compromise before the election happens, rather than after. You have to build a broad coalition just to get the nomination.

How to Actually Change It

If you’re tired of the binary, "voting harder" for a third party usually doesn't work because of the math we talked about. To change why the United States has a two party system, you have to change the mechanics of the election itself.

- Ranked Choice Voting (RCV): This is the big one. It's already happening in places like Alaska and Maine. You rank candidates in order of preference. If your first choice loses, your vote moves to your second choice. This kills the "spoiler effect" and lets people vote their conscience without fear.

- Proportional Representation: Instead of "winner-take-all" districts, seats could be given based on the percentage of the total vote.

- Open Primaries: Letting anyone vote in any primary prevents parties from moving to the extreme fringes.

The system isn't broken; it's performing exactly how it was designed based on the rules we use. If you want more than two flavors of ice cream, you have to change the way the shop is run.

What You Can Do Now

Don't just wait for the presidential election every four years. That's the least efficient way to impact the system.

Look into local ordinances regarding Ranked Choice Voting in your city or state. Groups like FairVote are working on this constantly. Also, pay attention to "fusion voting" (look at how New York does it), which allows third parties to cross-endorse candidates.

Understand that your local representative has way more impact on your daily life than the person in the White House, and at the local level, the two-party grip is sometimes a little looser. Start there. Expand the menu from the bottom up.

Next Steps for the Curious Voter:

- Research your state's ballot access laws to see how difficult it actually is for independent candidates to run.

- Support non-partisan primary initiatives if you want to see candidates who appeal to a broader base rather than just the "base" of their party.

- Use resources like Ballotpedia to track how third parties are performing in your specific district—you might find they have more sway in local town councils than on the national stage.