Orson Welles was broke. Again. By the early sixties, the man who made Citizen Kane was basically a cinematic nomad, wandering through Europe, taking acting gigs in mediocre movies just to fund his own visionary projects. Then came Alexander Salkind. He offered Welles the chance to adapt any masterpiece in the public domain. Welles spent a night reading. He considered Crime and Punishment but tossed it aside; he’d already done it on the radio. Then he hit Kafka.

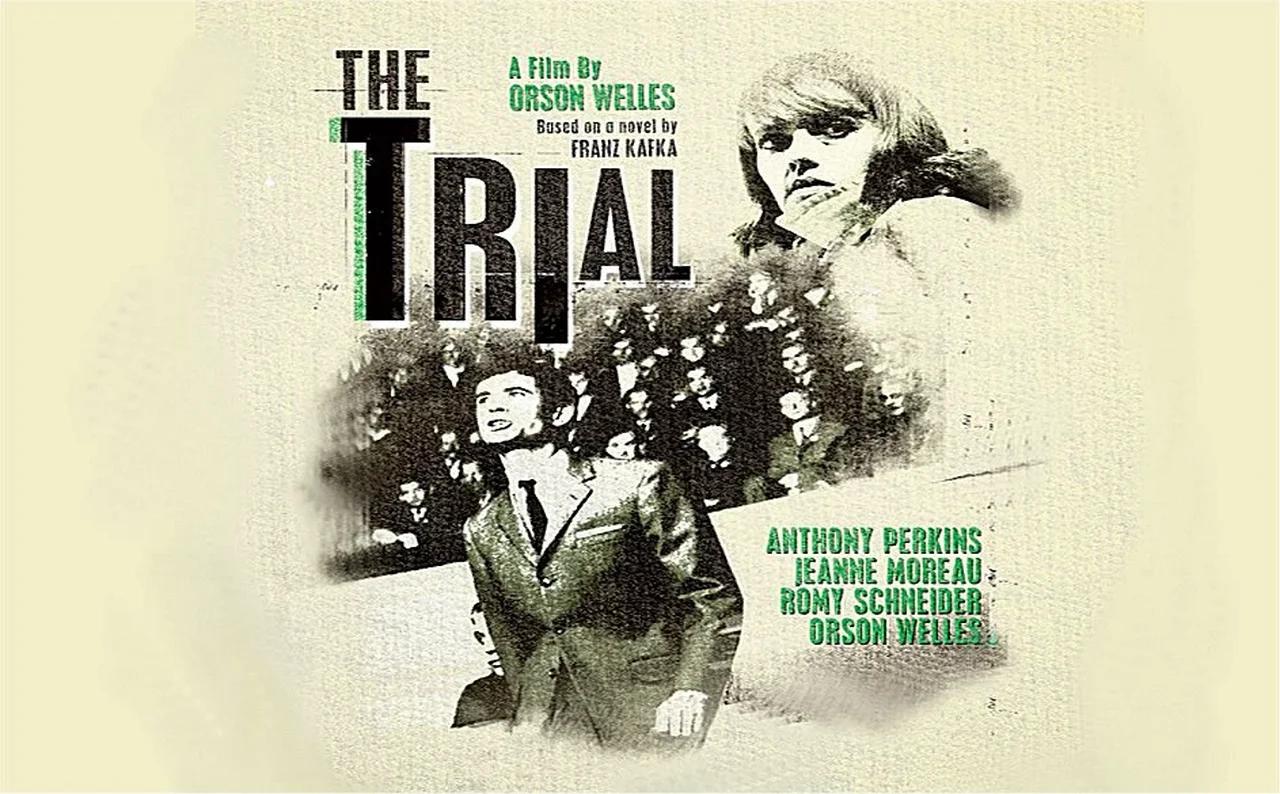

The Trial 1962 Orson Welles adaptation wasn’t just another job for him. It was a resurrection. He called it the best film he ever made. Better than Kane. That’s a massive claim, right? But when you look at the sheer, suffocating brilliance of what he put on screen, you start to see why he was so obsessed with it.

He didn't have the money for massive sets. Not at first. He was supposed to shoot in Yugoslavia, but the deal fell through. He ended up in the Gare d'Orsay, an abandoned, decaying railway station in Paris. It was cold. It was cavernous. It was perfect. This wasn't just a movie set; it was a physical manifestation of a nightmare.

The Nightmare of Josef K.

Anthony Perkins plays Josef K. Forget Psycho for a second. In The Trial 1962 Orson Welles, Perkins is twitchy, arrogant, and vulnerable all at once. He wakes up one morning and he’s under arrest. Why? Nobody knows. The guards don’t know. The Inspector doesn't know.

The brilliance of the film is how it captures that specific Kafkaesque dread. It’s the feeling of being trapped in a system that has no entrance and no exit. Welles used the Gare d'Orsay to create these impossible spaces. You see K. running down a hallway that seems to stretch for miles, only to end up in a room full of old men sitting at typewriters. The scale is intentional. It makes the individual look like an ant under a magnifying glass.

Welles himself plays the Advocate, Hastler. He’s huge, wrapped in blankets, surrounded by literal mountains of legal paperwork. He represents the stagnation of the law. He’s not there to help; he’s there to consume K.’s time and soul. Honestly, the way Welles shoots himself from low angles makes him look like a crumbling god. It’s intimidating as hell.

👉 See also: Christopher McDonald in Lemonade Mouth: Why This Villain Still Works

Sound as a Weapon

Most people focus on the visuals, but the sound design in The Trial 1962 Orson Welles is what actually gets under your skin. Welles was a radio genius first. He knew how to use audio to disorient an audience.

The echoes in this movie are haunting. Every footstep sounds like a gunshot. Voices carry across rooms in ways that don't make physical sense. Welles also dubbed a lot of the actors himself. If you listen closely, you’ll hear Welles’s distinctive baritone coming out of multiple characters. It creates this eerie, claustrophobic feeling that the entire world is just one person—the Creator—mocking the protagonist.

He used Albinoni's Adagio in G Minor throughout the score. It’s melancholy. It’s heavy. It hangs over the scenes like a funeral shroud. It wasn't just background music; it was a character.

Why the Ending Still Sparks Arguments

Kafka never finished the book. The manuscript was a mess of chapters. This gave Welles some creative license, and he took it. In the book, the ending is bleak. Two executioners lead K. to a quarry and "kill him like a dog."

Welles hated that.

✨ Don't miss: Christian Bale as Bruce Wayne: Why His Performance Still Holds Up in 2026

In The Trial 1962 Orson Welles, the ending is different. K. refuses to lie down. He fights back. He laughs at his executioners. When they throw a stick of dynamite into the pit with him, the explosion creates a mushroom cloud. It’s a direct reference to the nuclear anxiety of the 1960s. Welles argued that after the Holocaust, a "passive" death wasn't believable anymore. He wanted K. to represent the defiance of the human spirit, even in the face of total annihilation.

Some critics at the time hated it. They thought it was too loud, too flashy. But looking back, it’s a stroke of genius. It moves the story from a personal nightmare to a global one.

The Technical Wizardry of a Budget Film

You’d think a movie this visually complex would have a massive budget. It didn’t. Welles was a master of the "poor man's" special effect.

- Pin Screen Animation: The opening prologue, the "Before the Law" parable, was created using a pinscreen by Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker. It’s thousands of tiny pins pushed through a board to create shadows. It looks like a moving charcoal drawing.

- The Power of Scale: He used hundreds of extras in the office scenes to emphasize the crushing weight of bureaucracy.

- Light and Shadow: Using high-contrast cinematography (Chiaroscuro), Welles hid the fact that his sets were often just empty rooms in a train station.

He was editing this thing up until the very last minute. He was obsessed with the rhythm. The cuts are fast. Sometimes they're jarring. It’s meant to keep you off-balance. If you feel uncomfortable watching it, that means it's working.

The Legacy of the 1962 Masterpiece

It’s weird to think that The Trial 1962 Orson Welles was a bit of a flop when it first came out. People didn't know what to make of it. It was too "European" for Americans and too "Hollywood" for the Europeans. But time has been kind to it.

🔗 Read more: Chris Robinson and The Bold and the Beautiful: What Really Happened to Jack Hamilton

Today, it's studied in every film school. It influenced Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. It influenced David Lynch. Basically, any movie that features a protagonist trapped in a surreal, bureaucratic maze owes a debt to Welles’s Kafka.

It’s a film about the 20th century. It’s about the rise of the police state, the loss of privacy, and the feeling that we are all guilty of something, even if we don't know what it is. It’s more relevant now in the age of digital surveillance than it was in 1962.

Actionable Insights for Cinephiles

If you really want to understand the depth of this film, don't just watch it once. Here is how to actually digest it:

- Watch the 4K Restoration: For years, the only copies of this movie were grainy and terrible. The recent 4K restoration (released by Rialto Pictures/StudioCanal) is a revelation. You can actually see the textures of the Gare d'Orsay.

- Read the Parable First: Read the "Before the Law" short story by Kafka before hitting play. It’s only a few pages long. Understanding that parable makes the entire structure of the film click into place.

- Listen for the Dubbing: Pay attention to the voices. Once you realize Welles is voicing half the cast, the movie becomes a meta-commentary on the director as a "God" figure over his characters.

- Compare the Endings: Read the final chapter of Kafka's unfinished novel and then watch Welles's explosive finale. Decide for yourself if Welles's change was a betrayal of Kafka or a necessary update for the Cold War era.

The film is currently available on various boutique streaming services like the Criterion Channel or for rent on major platforms. It’s not an "easy" watch, but it’s one that will stick in your brain for weeks. Orson Welles didn't just film a book; he filmed a feeling. That feeling is the realization that the world doesn't care about your innocence.