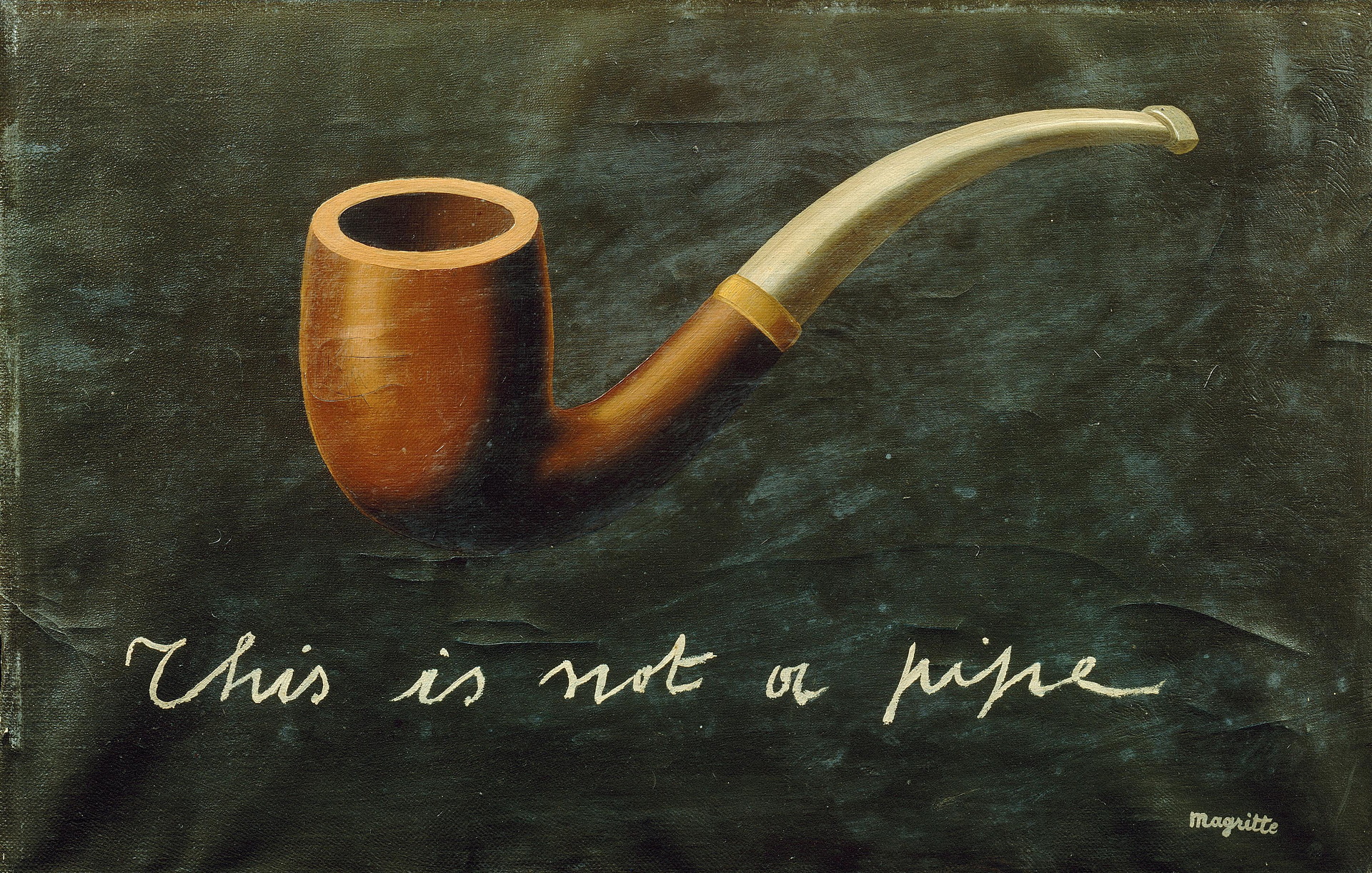

You’ve seen it. Even if you aren't an "art person," you’ve definitely seen the painting of the pipe with the cursive French script underneath it. It’s on T-shirts, it’s in The Fault in Our Stars, and it’s basically the original meme of the art world. But here’s the thing: most people look at The Treachery of Images by René Magritte and think, "Oh, it's just a clever joke about how a picture isn't the real thing."

That’s barely scratching the surface.

Magritte wasn't just being a smart-aleck. He was actually attacking the way our brains process reality. When he painted La Trahison des Images (the original French title) in 1929, he was 30 years old and living in a suburb of Paris, hanging out with the Surrealists. He wanted to prove that language and images are basically liars. It’s a bold claim. But once you realize what he was actually doing, you’ll never look at a digital screen or a photograph the same way again.

It Is Not a Pipe (No, Seriously)

The text at the bottom says Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

Translation: This is not a pipe.

Your first instinct is to call him a liar. "Of course it's a pipe, René. I'm looking right at it." But Magritte’s response was legendary and surprisingly blunt. He used to tell people that if he had written "This is a pipe" on the canvas, he would have been lying. Why? Because you can’t stuff tobacco in it. You can’t light it. You can’t smoke it. It’s just oil paint on a piece of fabric.

It sounds simple. Kinda obvious, right?

But we do this every single day. We look at a photo of a burger on an app and say, "That looks delicious," even though we’re actually just staring at glowing pixels. We confuse the representation with the reality. Magritte was obsessed with this gap—the space between the object, the image of the object, and the word we use to describe it. He was part of a movement that included thinkers like Ferdinand de Saussure, who were busy tearing apart linguistics and signs.

💡 You might also like: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

Magritte didn't want you to admire his brushwork. Honestly, the painting is intentionally flat. It looks like an advertisement from a 1920s catalog. That was on purpose. By using a "boring" commercial style, he stripped away the "artiness" of the piece so you’d focus entirely on the paradox. It’s a philosophical trap. You’re caught between your eyes telling you "Pipe!" and your brain reading "Not a pipe."

The tension is where the magic happens.

The Belgian Who Wanted to Be Invisible

René Magritte didn't look like a rebel. He didn't wear a paint-splattered smock or live a wild, bohemian life like Picasso. He lived in a quiet house in Brussels, wore a bowler hat, and worked in his dining room. He was the most "normal" looking guy in the history of art.

This anonymity was his superpower.

By looking like a boring businessman, he could launch these psychological grenades into the world of high art. The Treachery of Images by René Magritte was his loudest explosion. He wasn't just interested in pipes. Throughout his career, he painted apples, hats, and umbrellas, always trying to strip them of their "meaning."

He once said that his titles were not explanations. He wanted the title to act as an additional "image" that contradicted the visual. This is why the painting is so effective. If the painting had no text, it would just be a well-rendered pipe. If the text was in a book without the picture, it would be a random sentence. Together, they create a third thing: a feeling of total uncertainty.

Why 1929 Mattered

Context is everything. 1929 was the year of the Great Depression, but in the art world, it was the height of Surrealism. While guys like Salvador Dalí were busy painting melting clocks and dreamscapes, Magritte stayed in the "real" world. He realized that reality itself was weird enough.

📖 Related: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

He didn't need to paint monsters. He just needed to point out that the way we label the world is completely arbitrary.

Think about the word "dog." There is nothing inherently "dog-like" about the sound of that word or the letters D-O-G. We just all agreed on it. Magritte’s work reminds us that our entire understanding of the world is built on these flimsy agreements. If we decide tomorrow that a pipe is called a "glurp," the object doesn't change, but our reality does.

The Legacy of a Contradiction

You see Magritte’s DNA everywhere now.

Conceptual art basically wouldn't exist without him. When Joseph Kosuth put a real chair, a photo of a chair, and a dictionary definition of a chair in a gallery in 1965 (One and Three Chairs), he was just remixing Magritte. Even meme culture thrives on this. Every time someone posts a "This is fine" meme while their life is falling apart, they are playing with the treachery of images.

It’s about the distance between what we see and what is actually happening.

Modern advertising uses this trick constantly. They sell you a "feeling" or a "lifestyle" using images that have nothing to do with the product. Magritte saw it coming. He worked in advertising for years, designing wallpaper and posters, so he knew exactly how to manipulate the viewer's eye. He used those same manipulative techniques to tell the truth: that images are untrustworthy.

Common Misconceptions

People often think Magritte was a nihilist. They think he was trying to say that nothing matters or that nothing is real. That’s not quite right. Magritte loved the mystery of the world. He just hated the way we try to "explain" things away.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

- Misconception 1: He hated pipes. (He actually smoked them constantly.)

- Misconception 2: He was just a prankster. (He was deeply influenced by philosophy, specifically the works of Hegel and Heidegger.)

- Misconception 3: It’s a "Surrealist" painting because it’s weird. (It’s actually quite literal; the "weirdness" comes from the logic, not the visuals.)

The painting currently lives at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). If you ever go see it, you’ll notice it’s smaller than you expect. It’s about 23 by 37 inches. It’s intimate. It’s not a grand, sweeping masterpiece meant to overwhelm you. It’s a quiet conversation between the artist and your brain.

How to Apply "Magritte Thinking" to Your Life

So, what do we do with this? Is it just a cool fact for a trivia night?

Actually, understanding the treachery of images is a vital skill in the 2020s. We are drowning in images. Deepfakes, AI-generated art, Instagram filters, and curated social media feeds are the new "pipes."

When you look at a perfectly edited photo of someone’s vacation, you have to remind yourself: Ceci n’est pas une vie. This is not a life. It’s a representation. It’s a flat, curated, 2D version of a messy, 3D reality.

Actionable Steps for the "Post-Magritte" World:

- Audit your feed: Next time you feel a surge of envy or FOMO from an image, literally say "This is not a [thing]" out loud. It breaks the psychological spell.

- Question the labels: Magritte showed that words and images don't always match. When you see a news headline or a political ad, look for the gap between the "label" and the actual facts.

- Embrace the mystery: Stop trying to "figure out" art or life immediately. Sometimes, the point is the confusion itself.

- Visit the source: If you can, go see the painting at LACMA. There is a massive difference between seeing a JPEG of the pipe and seeing the actual brushstrokes. Ironically, seeing the physical "non-pipe" in person makes the point even stronger.

Magritte didn't want to solve the puzzle for you. He wanted you to realize that you've been living inside the puzzle your whole life. The treachery isn't in the paint; it's in the way we trust our eyes too much and our minds too little.

He’s still right. It’s still not a pipe. And you're still being tricked, every single day, by a thousand other images that claim to be the real thing. Once you see the lie, you start to see the truth.

Next Steps to Deepen Your Understanding:

- Research "Semiotics": If you want to know the "why" behind the painting, look up Ferdinand de Saussure. He explains the "Signifier" (the word/image) and the "Signified" (the actual concept).

- Explore Magritte’s other "Word-Paintings": Check out The Key of Dreams (1930). He takes the concept further by labeling a horse as "the door" and a clock as "the wind."

- Check out the LACMA Digital Collection: You can view high-resolution scans of the painting to see the "commercial" style of the brushwork up close, which helps you understand his intent to mimic advertising rather than "Fine Art."