It was weird. If you grew up in Hong Kong or visited between the 1950s and the 1990s, you probably remember a specific kind of fever dream high up on Tai Hang Road. It wasn't a park, exactly. It wasn't a temple. It was the Tiger Balm Garden Hong Kong, a sprawling, surrealist landscape of neon-painted plaster statues, jagged concrete grottos, and some of the most graphic depictions of the afterlife ever committed to rebar and cement. It’s gone now, mostly. Well, the garden part is. The mansion survives as a museum, but the "Eighteen Levels of Hell"—the stuff that actually gave kids nightmares—is a memory buried under luxury high-rises.

Aw Boon Haw built it. He was the "Tiger" of the Haw Par brothers, the eccentric Burmese-Chinese entrepreneurs who made a fortune selling that tingly herbal ointment we still use for mosquito bites and sore muscles. He didn't just want a backyard; he wanted a moral playground. He poured millions into a three-hectare vertical maze of Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian folklore. It was basically a 3D comic book designed to scare you into being a good person.

The Surrealism of the Haw Par Mansion

Walking into the Tiger Balm Garden Hong Kong felt like stepping into a saturated, psychedelic version of Chinese mythology. Everything was painted in blindingly bright primaries. Red, yellow, blue, and green—colors that felt almost edible but looked slightly menacing under the humid Hong Kong sun. You’d turn a corner and see a giant tiger standing on its hind legs, or a mermaid with a suspiciously human face lounging on a concrete rock. It was kitsch. It was art. It was terrifying.

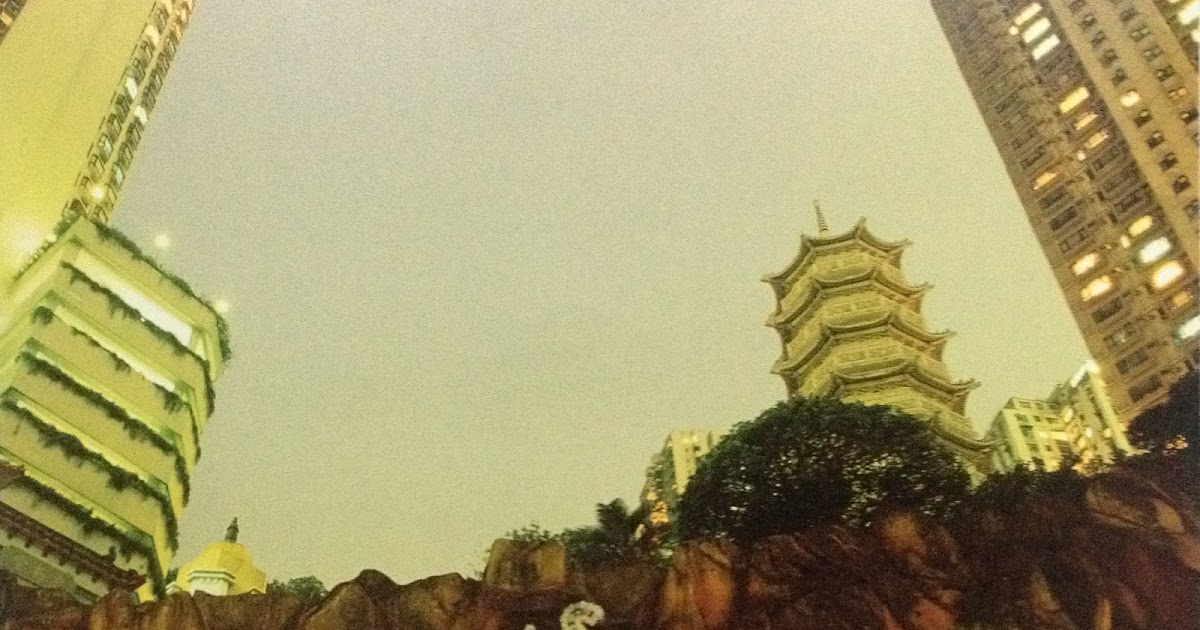

The centerpiece was the White Pagoda. Seven stories tall. It dominated the skyline of the Wan Chai district, a beacon of traditional architecture in a city that was rapidly turning into a forest of glass and steel. But the pagoda wasn't where the real action was. The real action happened in the caves.

Aw Boon Haw was obsessed with public education, or at least his version of it. He opened the gardens to the public for free because he wanted the common person to see the consequences of their actions. This wasn't subtle stuff. If you lied, a plaster demon was going to pull your tongue out with oversized pliers. If you were a tax evader, you were getting tossed into a giant wok of boiling oil. Honestly, it was visceral. The statues weren't masterpieces of fine art—they were chunky, expressive, and deeply unsettling.

🔗 Read more: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

The Ten Courts of Hell

This was the main event. Most visitors didn't come for the pretty flowers; they came to see the carnage. The Ten Courts of Hell depicted the various punishments awaiting sinners in the afterlife. It was a grisly, low-budget horror movie rendered in sculpture. You saw people being sawn in half, crushed by boulders, and pecked by birds.

It’s easy to dismiss this as low-brow, but there was a genuine cultural weight to it. For many in the post-war generation, these gardens were a primary way of interacting with traditional folklore. Before the internet, before massive theme parks, you had the Tiger Balm Garden. It was a shared cultural touchstone that spanned generations. My dad saw it. I saw it. The kids of the 80s saw it. We all remember that one specific statue of a woman being turned into a pig. It stays with you.

Why did it disappear?

Land in Hong Kong is gold. Actually, it's more expensive than gold. By the late 1990s, the Haw Par family’s empire had shifted. Aw Boon Haw had passed away decades earlier, and the maintenance on a garden filled with crumbling plaster statues in a salty, humid climate was astronomical. It started to look shabby. The paint peeled. The demons looked more like they were melting than punishing.

In 1998, the garden was sold to Cheung Kong Holdings. The development giant, led by Li Ka-shing, did what developers do. They saw land value, not a weird mythological park. By 2004, the garden was demolished to make way for The Legend—a high-end residential complex. It was a massive loss for Hong Kong’s "weird" heritage.

💡 You might also like: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

However, the Haw Par Mansion itself—the actual residence of the family—was saved. It’s a Grade I historic building. It’s a strange mix of Chinese and Western styles, featuring stained glass windows with Chinese motifs and Italianate columns. For a while, it operated as a music school (Haw Par Music), but that closed down too. It’s a bit of a ghost now, sitting there amongst the shiny towers, a remnant of a time when billionaires built public parks instead of just more shopping malls.

The Contrast with Singapore

If you’re really craving that weird Tiger Balm vibe, you have to go to Singapore. The sister park, Haw Par Villa, still exists. It’s actually been renovated. It’s just as strange, just as bloody, and just as colorful. But the Hong Kong version was different. It was more vertical. It was built into the side of a mountain, reflecting the cramped, upwards-striving energy of the city itself. Losing it felt like losing a piece of Hong Kong's soul—the part that wasn't about finance or efficiency, but about folk stories and tingly ointment.

What’s left to see today?

If you go to Tai Hang today, you won't see the Hell scenes. You won't see the statues of the monkey king or the giant tiger. But the Haw Par Mansion is still there, standing at 15A Tai Hang Road. The government took it back in 2001, and while its future as a public venue has been a bit of a rollercoaster, the facade remains.

- The Architecture: Look at the roof tiles. They are green-glazed and stunning. The mansion is a rare example of the "Chinese Renaissance" style that was popular among the wealthy elite in the 1930s.

- The Stained Glass: The interior windows are some of the most unique in the city. They depict scenes that feel both Art Deco and traditionally Cantonese.

- The Vibe: Even without the statues, the site feels heavy. It’s tucked away from the main bustle of Causeway Bay. It’s quiet. You can still feel the presence of the "Tiger" who once walked these grounds.

People often ask if it was a "theme park." Not really. Not in the way we think of Disneyland. There were no rides. No popcorn stands. No costumed characters. It was a stroll through a feverish imagination. It was a place where you’d take a date just to see if they had a sense of humor, or where parents would take children to ensure they'd think twice before stealing a cookie.

📖 Related: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

The Legacy of the Tiger

The Tiger Balm Garden Hong Kong was a victim of its own location. In any other city, it might have been preserved as a quirky historical site. In Hong Kong, every square foot has to justify its existence in dollars. Plaster demons don't pay rent.

But the memory persists. You see it in the work of local artists who grew up with those images. You see it in the nostalgic photography books that fill the shops in PMQ or Tai Kwun. It represents a Hong Kong that was a bit more chaotic, a bit more colorful, and a lot more eccentric.

Honestly, we need more of that. We have enough glass boxes. We have enough luxury malls with the same five brands. We need more places that are built out of someone's weird, sincere desire to teach the public about the afterlife using brightly painted cement.

Actionable insights for the modern explorer

If you want to experience what's left of the Tiger Balm legacy, you have to be intentional. Don't just show up expecting a theme park.

- Check the Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO) website before you go. The mansion's opening hours and public access fluctuate depending on who is managing the site. It’s currently in a transition phase after the music school moved out.

- Combine the trip with a visit to Tai Hang village. It’s right down the hill. Tai Hang has managed to keep its "old Hong Kong" neighborhood feel despite the gentrification. During the Mid-Autumn Festival, this is where the Fire Dragon Dance happens. It’s the perfect companion to the mythological energy of the Haw Par Mansion.

- Look for the Tiger Balm itself in any local pharmacy. The packaging hasn't changed much in decades. The hex-shaped jar is a piece of industrial design history that you can buy for about twenty bucks.

- Research the Haw Par Villa in Singapore if you want to see the "complete" vision. It’s the only place where the Ten Courts of Hell still stand in their full, terrifying glory.

- Don't forget to look up. When you are standing near the mansion, look at the towering luxury flats above it. That's the visual story of Hong Kong: the ancient folklore literally being overshadowed by the relentless pursuit of real estate.

The garden is a ghost. But ghosts in Hong Kong are important. They remind us that under the concrete and the steel, there's a layer of stories, myths, and a very specific kind of herbal-scented ambition that built this city.

To really understand the site, you have to look past the absence of the statues. You have to see the mansion as a monument to a family that came from nothing and built a global brand out of a small apothecary in Rangoon. The garden was their gift to a city that welcomed them. Even if most of it is gone, the fact that the mansion remains is a small victory for heritage in a city that usually prefers the new. Go there. Walk the perimeter. Imagine the screams of the plaster sinners. It’s the most Hong Kong thing you can do.