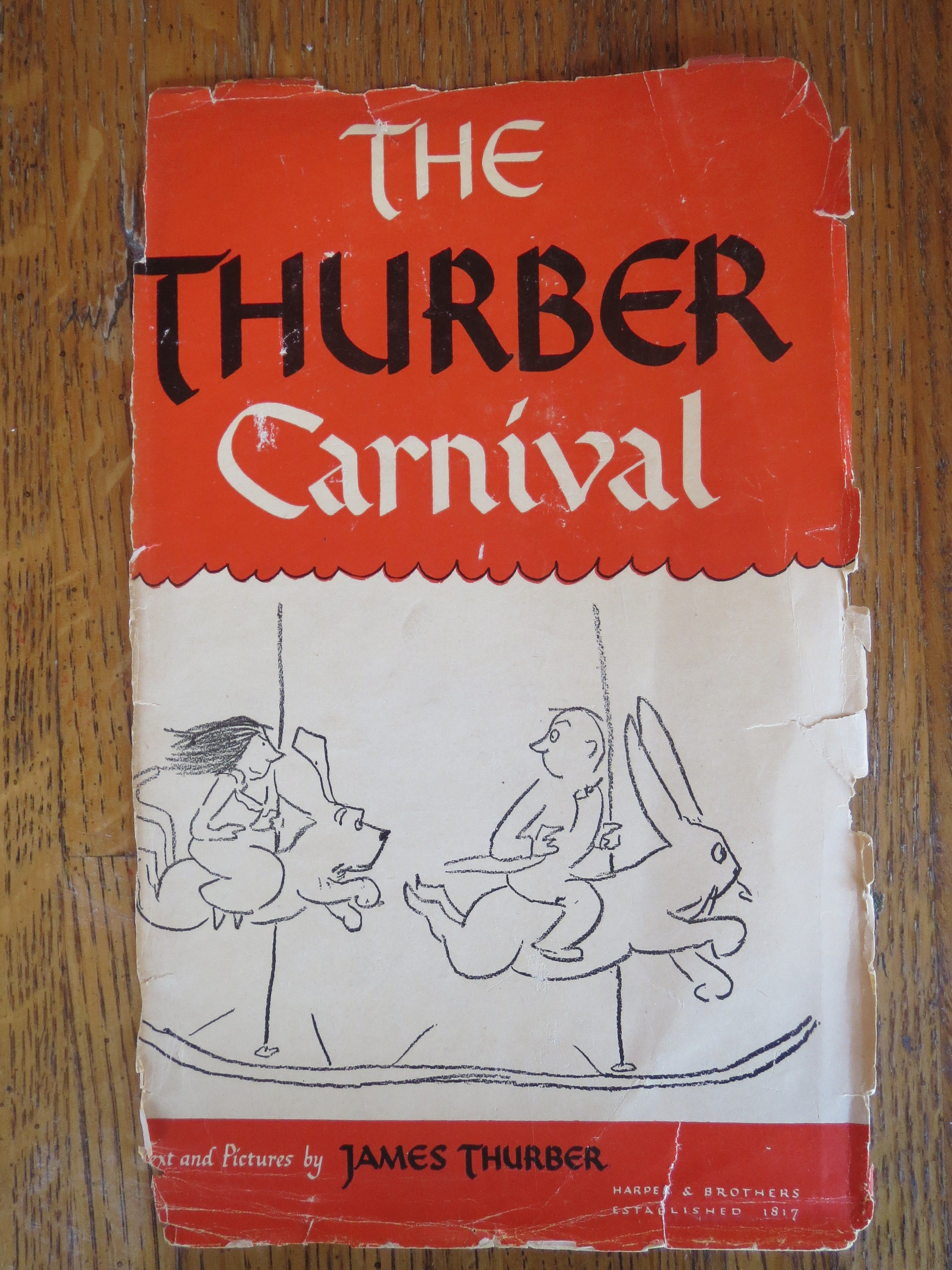

James Thurber was kind of a mess, and that’s exactly why we still need him. If you pick up a copy of The Thurber Carnival, you aren’t just looking at a dusty relic of mid-century humor. You’re looking at the blueprint for modern neurosis. Published in 1945, this anthology captured the absolute best of Thurber’s work from The New Yorker, and honestly, it’s a miracle it ever got compiled given how much the man struggled with his eyesight and his own internal chaos.

It’s a big book. It’s heavy. It’s filled with those wiggly, unshaded line drawings of dogs that look more human than the people do, and men who look like they’re about to have a nervous breakdown over a toaster.

Thurber didn't write about grand political shifts or epic wars, even though he lived through two of them. He wrote about the war between men and women, the war between humans and machines, and the strange, quiet war between a man and his own imagination. If you’ve ever felt like the world was slightly too loud or that your own thoughts were becoming increasingly surreal, you’ll find a home in these pages.

The Weird Genius of The Thurber Carnival

What makes The Thurber Carnival the definitive collection is the sheer variety. You’ve got short stories, fables, and those "My Life and Hard Times" essays that are basically the gold standard for memoir writing. He takes mundane stuff—like a car breaking down or a grandfather who thinks the Civil War is still happening—and turns it into something transcendent.

He was a master of the "Little Man" trope.

This wasn't the heroic, square-jawed American male of the 1940s. This was a guy who was terrified of his wife, confused by his electricity, and deeply, deeply concerned about his dog’s opinion of him. In "The Night the Ghost Got In," the chaos starts because the narrator hears a noise and ends with the police nearly shooting his grandfather. It’s hysterical because it feels real. We’ve all had those nights where a small misunderstanding spirals into a total catastrophe.

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

You can't talk about this book without mentioning Mitty. Forget the Ben Stiller movie for a second—the original short story in this collection is only a few pages long, and it’s devastating. Mitty is a man being nagged while he drives his wife to the hairdresser, but in his head, he’s a daring pilot or a world-class surgeon.

🔗 Read more: Cast of Troubled Youth Television Show: Where They Are in 2026

It hits hard because it's about the tragedy of the mundane.

Thurber knew that most people live lives of quiet desperation, fueled by "pocketa-pocketa-pocketa" sounds of imaginary engines. It’s probably the most famous story in the book, and for good reason. It gave us a word. We call people "Mitty-esque" now. That’s real cultural power.

Why the Drawings Look So Weird

People always ask about the art. Thurber wasn't a "trained" artist in the traditional sense. In fact, by the time The Thurber Carnival came out, he was nearly blind. He used a Zeiss Magnifier and eventually drew on giant sheets of paper with neon lights just to see what he was doing.

The result? Those famous, blobby, emotional drawings.

- The dogs are iconic. They are mostly English Bloodhounds, but they represent a sort of stoic wisdom that the humans lack.

- The "Thurber Woman" is usually formidable, large, and slightly menacing.

- The "Thurber Man" is small, balding, and looks like he's hiding behind a curtain.

Dorothy Parker once said that these drawings looked like "unbaked cookies," which is spot on. But there’s a rawness to them. They aren't polished because life isn't polished. They capture a feeling—usually one of mild panic—better than a hyper-realistic painting ever could.

The Fables for Our Time

Tucked into the back of the collection are the fables. These aren't Aesop’s fables. There’s no easy moral that makes you feel good about yourself. Usually, the moral is something like "You might as well fall on your face as lean too far backward."

💡 You might also like: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

He takes these classic setups—a crow and a fox, or a unicorn in the garden—and flips them. In "The Unicorn in the Garden," a man sees a mythical beast, tells his wife, and she tries to have him committed to a "booby hatch." It’s dark. It’s cynical. It’s also incredibly funny if you’ve ever been in a relationship where communication has completely broken down.

The Enduring Legacy of the 1945 Edition

When Harper & Brothers first released this, it was a massive hit. It was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. It stayed on the bestseller lists for weeks. Why? Because after the trauma of World War II, people needed to laugh at the absurdity of existence. They needed to know that it was okay to be a bit broken and confused.

Thurber’s prose is deceptively simple. He doesn't use big, flashy words. He uses short, punchy sentences that build a rhythm.

"The car knocked."

"My mother screamed."

He gets straight to the point. But within that simplicity, he weaves in complex psychological truths. He understood anxiety before we had a clinical vocabulary for it. He understood that the modern world—with its gadgets and its social expectations—is a minefield for the sensitive soul.

📖 Related: Carrie Bradshaw apt NYC: Why Fans Still Flock to Perry Street

Misconceptions About Thurber

Some folks think he was just a "humorist." That’s a bit of a slight. Being a humorist is harder than being a tragedian because you have to be accurate to be funny. If you miss the truth by a fraction of an inch, the joke fails.

Others think he was a misogynist. It’s true, his female characters are often the antagonists. But if you look closer, the men are just as flawed. They’re weak, indecisive, and trapped in their own heads. Thurber wasn't attacking women; he was satirizing the power dynamics of the suburban household of his era. It’s a caricature of a specific time and place, but the underlying feeling of "I don't fit in here" is universal.

How to Read The Thurber Carnival Today

Don't try to read it cover to cover in one sitting. You'll get a headache. It's too much wit for one go. Instead, treat it like a tasting menu.

- Start with "The Night the Bed Fell." It’s the perfect introduction to his family’s particular brand of insanity.

- Move to the "War Between Men and Women" drawings. Look at the body language. It’s silent comedy on the page.

- Read "The Catbird Seat." It’s a brilliant little revenge story about a man who uses his own boring reputation as a weapon.

- End with the fables. They’ll leave you feeling a little uneasy, which is exactly how Thurber wanted you to feel.

The book is a time capsule. You get a sense of 1930s and 40s New York, the clink of martini glasses, the smell of tobacco smoke, and the sound of a typewriter clacking away in a small office at The New Yorker. But the people? They’re just like us. They’re worried about their jobs, their pets, and whether they’re going crazy.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Reader

If you want to actually "get" Thurber, don't just read the words—look at the context.

- Find an original hardback: The paper quality and the layout of the 1945 edition are part of the experience. The drawings need space to breathe.

- Visit the Thurber House: If you’re ever in Columbus, Ohio, go to his childhood home. You’ll see the actual stairs where the "ghost" supposedly walked. It grounds the fiction in a very strange reality.

- Pair it with E.B. White: Thurber and White were roommates and collaborators. Reading Is Sex Necessary? (which they co-wrote) gives you a great sense of how they bounced ideas off each other.

- Listen to a reading: Some of his stories, like "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty," are even better when read aloud. The cadence of his writing is very musical.

Ultimately, The Thurber Carnival is a reminder that being human is an inherently ridiculous business. It’s a defense of the daydreamer, the misfit, and the person who just can’t seem to get their car started. It’s not just a book of jokes; it’s a manual for surviving the absurdity of life with a little bit of dignity intact. Or at least, with a good story to tell afterward.