Dr. Seuss had a weird way of making chaos feel productive. You know the story. It's raining. The kids are bored. Suddenly, a giant cat in a hat shows up and ruins the living room. But the real shift in the energy of The Cat in the Hat happens the moment that red box opens. Out jump Thing 1 and Thing 2.

They’re agents of pure, unadulterated anarchy.

Honestly, if you look at the Thing 1 and Thing 2 book—which is really just the debut of these characters in the 1957 classic—it’s a masterclass in childhood anxiety and liberation. Most people remember the blue hair. They remember the red onesies. But we rarely talk about what these two actually represent in the context of 1950s literacy. Before Theodor Geisel (Seuss) stepped in, kids were stuck with Dick and Jane. Those books were boring. They were sterile. Seuss wanted to kill Dick and Jane. He did it by unleashing two creatures that literally fly kites inside a house.

The Secret History of the Thing 1 and Thing 2 Book

In 1954, Life magazine published a report on why children weren't learning to read. The verdict? School primers were too "whitebread" and lacked "blood and guts." William Spaulding, then the director of the education division at Houghton Mifflin, challenged Seuss to write a book that "primers couldn't put down." He gave him a list of about 250 words that every first grader should know.

Seuss almost gave up.

He found the list incredibly restrictive. But then, he saw the word "cat" and the word "hat." The rest is history. However, the inclusion of Thing 1 and Thing 2 was the stroke of genius that moved the book from a simple rhyme to a psychological drama. These characters aren't villains, but they aren't heroes either. They are "Things."

Think about that naming convention for a second. It’s kinda dehumanizing, right? Yet, they are the most energetic beings in the entire narrative. They don't speak. They just "do." They represent the id—the part of the child's brain that wants to knock over the lamp just to see it break.

Why the visual design worked

Geisel was a perfectionist. If you look at the original sketches for the Thing 1 and Thing 2 book sequences, the line work is frantic. He used a very specific shade of cyan for their hair. It pops against the red. It’s primary-color-theory 101, but it worked because it felt "alien" to the muted palette of most 1950s children's literature.

🔗 Read more: Did Mac Miller Like Donald Trump? What Really Happened Between the Rapper and the President

They don't have ears. They don't have noses. They are just shapes with limbs. This was intentional. By making them less "human," Seuss allowed children to project their own mischief onto them. You aren't "bad" if you act like Thing 1; you're just being a "Thing." It gave kids a safe way to explore the idea of making a mess.

The Controversy You Probably Forgot

Believe it or not, the Thing 1 and Thing 2 book (and the Cat in the Hat series as a whole) has faced its fair share of criticism over the decades. It’s not just about the mess.

In recent years, scholars like Philip Nel and others have looked at the "Cat" character through the lens of minstrelsy. While Thing 1 and Thing 2 are usually seen as separate from those specific critiques, they are part of a larger "trickster" tradition that some find problematic.

Then there’s the parenting angle.

Some child psychologists in the 60s and 70s actually worried that the book encouraged disobedience. The Cat—and by extension, the Things—ignores the "Fish," who acts as the moral compass or the "super-ego" of the story. The Fish is screaming about rules, and the Things are literally pinning the Fish to a wall while they play. For a conservative 1950s audience, this was borderline revolutionary. It was the first time a mainstream children's book said: "The adults are away, and the chaos is actually kinda fun."

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

People remember the house getting cleaned up. They remember the magical machine with the many arms that picks up the cake, the rake, and the gown.

But they forget the last page.

💡 You might also like: Despicable Me 2 Edith: Why the Middle Child is Secretly the Best Part of the Movie

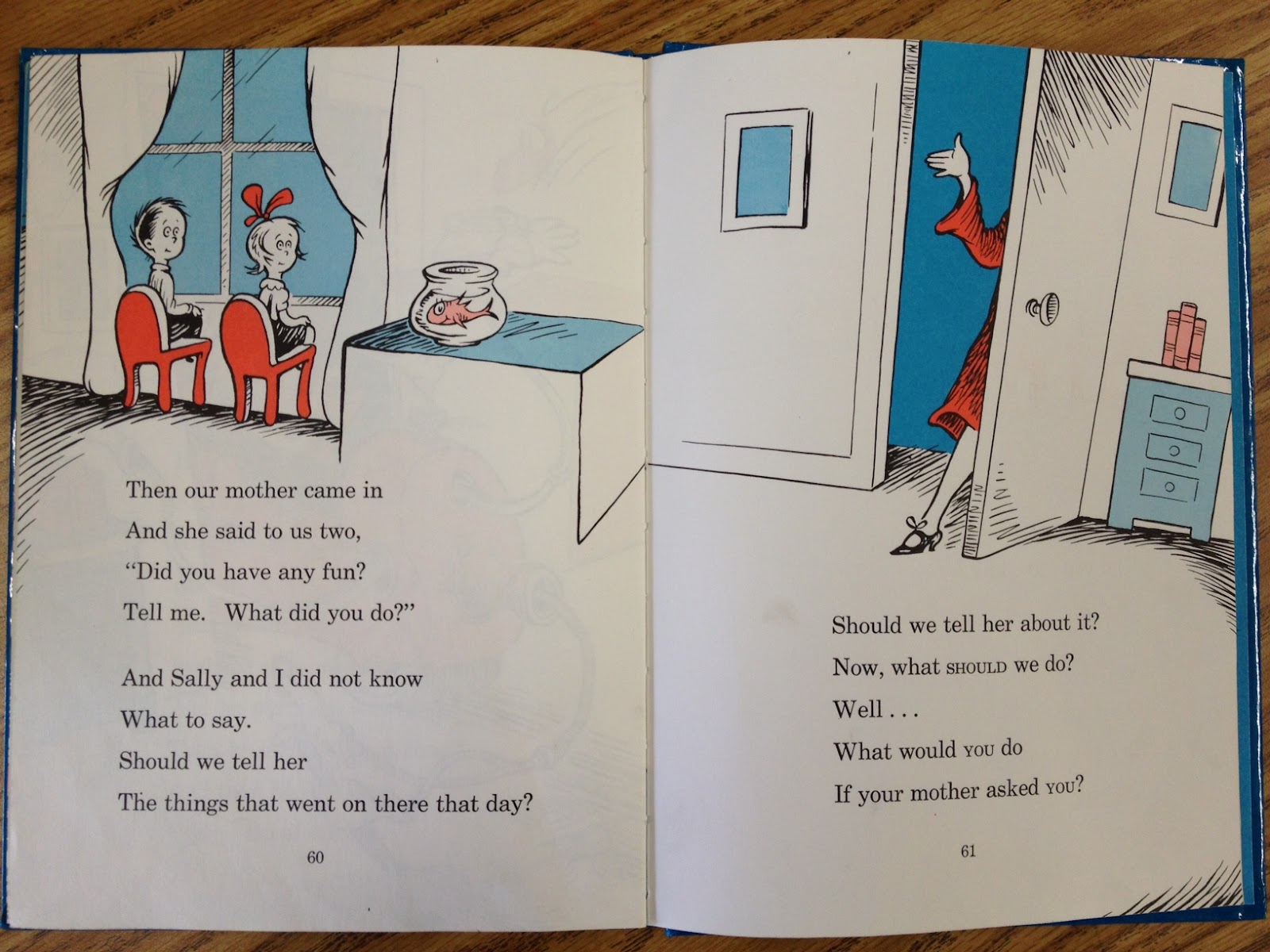

The mother comes home. She asks, "Did you have any fun? Tell me. What did you do?"

The book ends with a question to the reader: What would YOU do if your mother asked YOU? That is a heavy moment for a six-year-old. It moves the Thing 1 and Thing 2 book from a fantasy into a moral dilemma. Do you lie to your parents to protect the "magic" of the day? Or do you tell the truth and risk the consequences? Seuss never answers it. He leaves the child standing in the tension of that choice.

The "Thing" Brand vs. The "Thing" Reality

Today, you see Thing 1 and Thing 2 on t-shirts for twins. You see them on coffee mugs. They’ve been "Disney-fied" in a way, turned into cute mascots. But in the original text, they are actually pretty terrifying.

They run through the hall. They "thump" things. They have no regard for the mother's "best professional dress." When the boy finally catches them with the net, he's actually quite aggressive about it. He's had enough. The transition from "this is fun" to "this is too much" is the core lesson of the book, and the Things are the catalysts for that realization.

Nuance in the Animation

If you’ve seen the 1971 animated special, you’ll notice the Things are even more chaotic. Their movements are fluid and unpredictable. The voice acting (or lack thereof, mostly squeaks and gibberish) adds a layer of "otherness."

Compare that to the 2003 live-action movie.

Most Seuss fans hate that movie. Why? Because it tried to give the Things a "backstory" or make them too "gross-out" funny. It missed the point. The Things work because they are ciphers. They don't need a motive. They don't need a joke. They just need to exist as a force of nature.

📖 Related: Death Wish II: Why This Sleazy Sequel Still Triggers People Today

How to Use This Book Today

If you're reading the Thing 1 and Thing 2 book to a kid today, you've got to lean into the voices. It's a rhythmic experience. Seuss wrote in anapestic tetrameter. It’s a "da-da-DUM, da-da-DUM" beat.

- "They will shake hands with you."

- "They will NOT bite you."

It’s meant to be read fast. It’s meant to feel like a runaway train.

Actionable insights for parents and teachers

Don't just read the words. Use the Things to talk about boundaries.

- The "Net" Discussion: Ask the kid why the boy decided to catch the Things. At what point did the "fun" stop being fun? This is a huge lesson in emotional regulation.

- The "Truth" Dilemma: Discuss that final question. Would you tell your mom? Why or why not? It’s a great way to gauge a child’s understanding of honesty vs. privacy.

- Creative Chaos: Let kids draw their own "Thing." If they were Thing 3 or Thing 4, what would they look like? What would they "thump" in the house?

The Thing 1 and Thing 2 book is more than just a nostalgic trip. It’s a look at the duality of childhood—the urge to create and the urge to destroy. Seuss knew that kids weren't just "little angels." He knew they were messy, complicated, and sometimes a little bit "Thing-like."

Next time you open that red cover, look at the background details. Notice how the Fish is the only one looking at the "camera" (the reader). He's our proxy. He's us. And the Things? They’re exactly who we wish we could be on a rainy Tuesday afternoon when there’s nothing to do.

To get the most out of the experience, try reading the book without showing the pictures first. Let the child imagine what a "Thing" looks like based only on the sound of their names and the chaos they cause. Then, reveal Geisel’s iconic illustrations. It’s a fantastic exercise in visualization that highlights why these specific character designs have endured for nearly 70 years. You can also look for the "Beginner Books" seal on the cover to ensure you have the version intended for early literacy development.