It starts with a glass of water. Or maybe it starts with a tooth hidden in a hole in the wall. Roman Polanski’s The Tenant 1976 is a weird, sweaty, claustrophobic nightmare that doesn't just watch like a movie; it feels like a fever dream you can’t wake up from. Honestly, if you’ve ever lived in a big city with neighbors who complain if you breathe too loud, this movie will hit you way harder than any jump-scare slasher.

Trelkovsky is just a guy. He’s played by Polanski himself, looking small and perpetually anxious. He needs an apartment in Paris. He finds one, but there’s a catch: the previous tenant, Simone Choule, tried to kill herself by jumping out the window. She’s still clinging to life in the hospital, wrapped like a mummy in bandages. Trelkovsky visits her. She screams. She dies. He moves in.

And that’s when the walls start closing in.

The Apartment Trilogy’s Darkest Hour

People always talk about Rosemary’s Baby and Repulsion. Those are the big hits. But The Tenant 1976 is the final, most unhinged entry in Polanski's "Apartment Trilogy." While the first two movies dealt with external cults or internal mental breaks, this one is about the terrifying way society forces you to stop being yourself. It’s based on Roland Topor’s novel Le Locataire Chimérique, and if you’ve ever read Topor, you know he wasn’t interested in "happily ever after." He was into the grotesque.

The film was basically trashed when it first came out. Critics at Cannes hated it. They thought it was too much, too gross, too confused. But time has been kind to this movie. It’s now seen as a masterpiece of psychological horror because it captures something very specific: the loss of identity.

Trelkovsky isn’t just a victim of a haunting. He’s a victim of the "polite" society around him. His neighbors are monsters. They aren't monsters with fangs; they’re monsters who demand absolute silence and conformity. There’s Monsieur Zy (played by the legendary Melvyn Douglas), who acts like the patriarch of the building but is really just a tyrant. He tells Trelkovsky how to live, what to think, and essentially how to be Simone Choule.

Why Paris Feels Like a Prison

Paris in the 70s wasn't all baguettes and romance in Polanski's eyes. It was gray. It was damp. The cinematography by Sven Nykvist—who usually worked with Ingmar Bergman—is incredible here. It makes the apartment look like a trap.

📖 Related: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

There’s this one scene where Trelkovsky looks across the courtyard and sees people just... standing in the bathroom. They aren't doing anything. They’re just standing there, staring back. It’s deeply unsettling because it taps into that primal fear of being watched in your most private moments. You're never alone in an apartment building, even when you're by yourself.

The Slow Descent Into Simone Choule

This is where the movie gets truly bizarre. Trelkovsky starts becoming the woman who lived there before him. He starts wearing her clothes. He buys her favorite brand of cigarettes. He drinks what she drank. Is he possessed? Is he having a psychotic break? Or are the neighbors literally gaslighting him into replacing her?

Polanski doesn't give you an easy answer. That's what makes it great.

The physical transformation is jarring. We see him in a wig and a dress, looking in the mirror, and the horror isn't that he's a man in "drag"—it’s that he has completely lost the "Trelkovsky" version of himself. He has become a puppet.

Small Details That Rot Your Brain

The film is full of these tiny, horrific moments that stick with you:

- The tooth found in the wall, wrapped in cotton.

- The neighbors signing a petition against a woman who did nothing wrong.

- The way the furniture seems to grow larger or the room seems to shrink.

- That haunting, screeching score by Philippe Sarde.

It’s about the bureaucracy of living. You have to sign papers. You have to pay rent. You have to be quiet. If you don’t, you're erased.

👉 See also: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

The Controversy and the Legacy

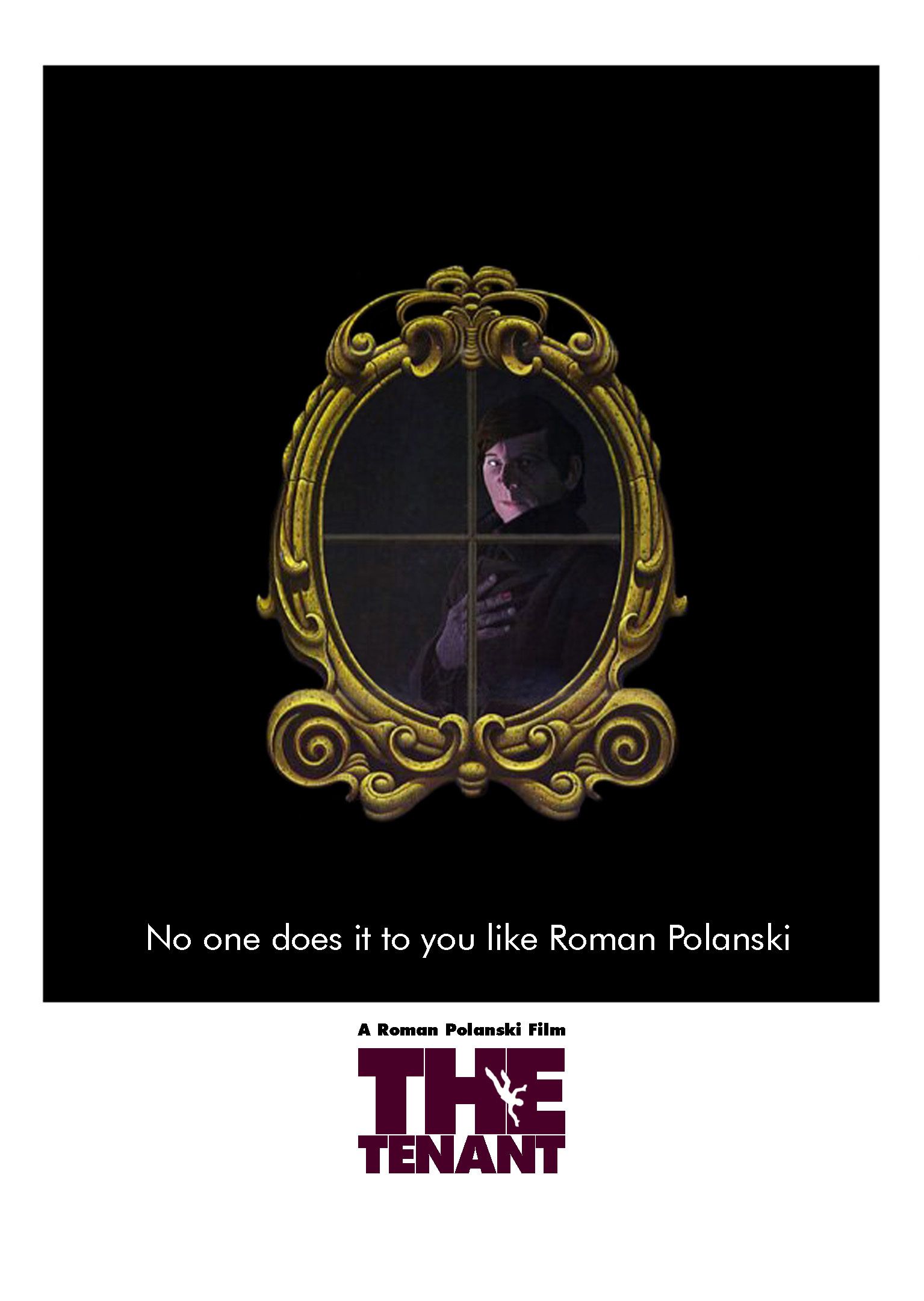

We have to acknowledge the elephant in the room. Talking about The Tenant 1976 means talking about Roman Polanski. The film was made just a few years after the Manson murders destroyed his life in the US and shortly before his own criminal charges and flight from the country. You can feel that paranoia on screen. It’s a movie made by a man who felt the world was out to get him. Whether you can separate the art from the artist is a personal call, but from a purely cinematic standpoint, the film is an undeniable piece of surrealist history.

It influenced everything. You can see DNA of The Tenant in David Lynch’s Eraserhead. You can see it in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan. Anytime a movie features a protagonist losing their mind in a cramped urban space, they owe a debt to Trelkovsky.

What You Should Look For on a Re-watch

If you’ve already seen it, watch it again and pay attention to the windows. The courtyard is its own character. The way the camera moves across the open space, peering into other lives, creates a sense of voyeurism that makes Rear Window look like a Disney movie.

Also, look at the language. Trelkovsky is a foreigner in France. He’s trying so hard to fit in, to be "a good Frenchman." That immigrant anxiety adds a whole other layer of stress. He’s terrified of being kicked out, so he accepts every insult and every weird demand from his landlord until there’s nothing left of his original personality.

The Ending That Circles Back

The ending is one of the most famous "loops" in cinema. Without spoiling it for the three people who haven't seen a 50-year-old movie: it suggests that this cycle of misery is infinite. The apartment is a stomach, and it’s always hungry for a new tenant.

Actionable Insights for Fans of Psychological Horror

If the themes of The Tenant 1976 resonated with you, there are a few ways to dive deeper into this specific sub-genre of "urban paranoia" without just re-watching the same film.

✨ Don't miss: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Read the source material

Track down a copy of The Tenant (Le Locataire Chimérique) by Roland Topor. It’s even more surreal than the movie. Topor was part of the "Panic Movement" with Alejandro Jodorowsky, and his prose reflects that chaotic, absurdist energy.

Explore the rest of the trilogy

If you haven't seen Repulsion (1965) or Rosemary's Baby (1968), do it. Watch them in order of release. You'll see how Polanski’s view of the "home" shifts from a place of isolation to a place of conspiracy and finally to a place of total identity erasure.

Check out "The Servant" (1963)

While not a horror movie in the traditional sense, Joseph Losey’s The Servant deals with the same kind of power dynamics and psychological takeover within the walls of a single house. It’s a great companion piece for understanding how spaces change people.

Analyze the "Sven Nykvist" look

Watch Bergman’s Persona or Cries and Whispers right after this. You’ll see how Nykvist uses lighting to create psychological depth. In The Tenant, he uses shadows not just to hide things, but to suggest that the rooms themselves are sentient.

Consider the "Urban Horror" context

Watch The Tenant alongside 70s New York "gritty" films like Taxi Driver. Compare how Paris and New York were portrayed as decaying, hostile environments that broke the people living in them. It provides a fascinating look at the mid-70s global anxiety about city life.

The film is a reminder that the most dangerous thing isn't a ghost in the attic. It's the person living in 3B who thinks you're making too much noise.