Calculus classes often feel like a fever dream of arbitrary rules. You spend weeks memorizing derivatives, only to be hit with power series. It feels like busywork. But honestly? The Taylor series of sin is basically the reason your smartphone can render 3D graphics and why GPS satellites don't lose track of your car.

It’s not just a math trick. It’s an approximation powerhouse.

Think about the sine function for a second. It’s wavy. It goes up and down forever between -1 and 1. If you ask a computer "Hey, what is $sin(0.523)$?", the computer doesn't have a giant lookup table with every possible decimal. That would be a storage nightmare. Instead, it uses a polynomial. Polynomials are easy. Computers love adding and multiplying. They hate wavy, transcendental curves.

The Weird Logic of Approximating Waves

The Taylor series of sin looks like a string of odd-powered terms. It's an alternating series. That means you add a bit, then subtract a bit, then add a bit more.

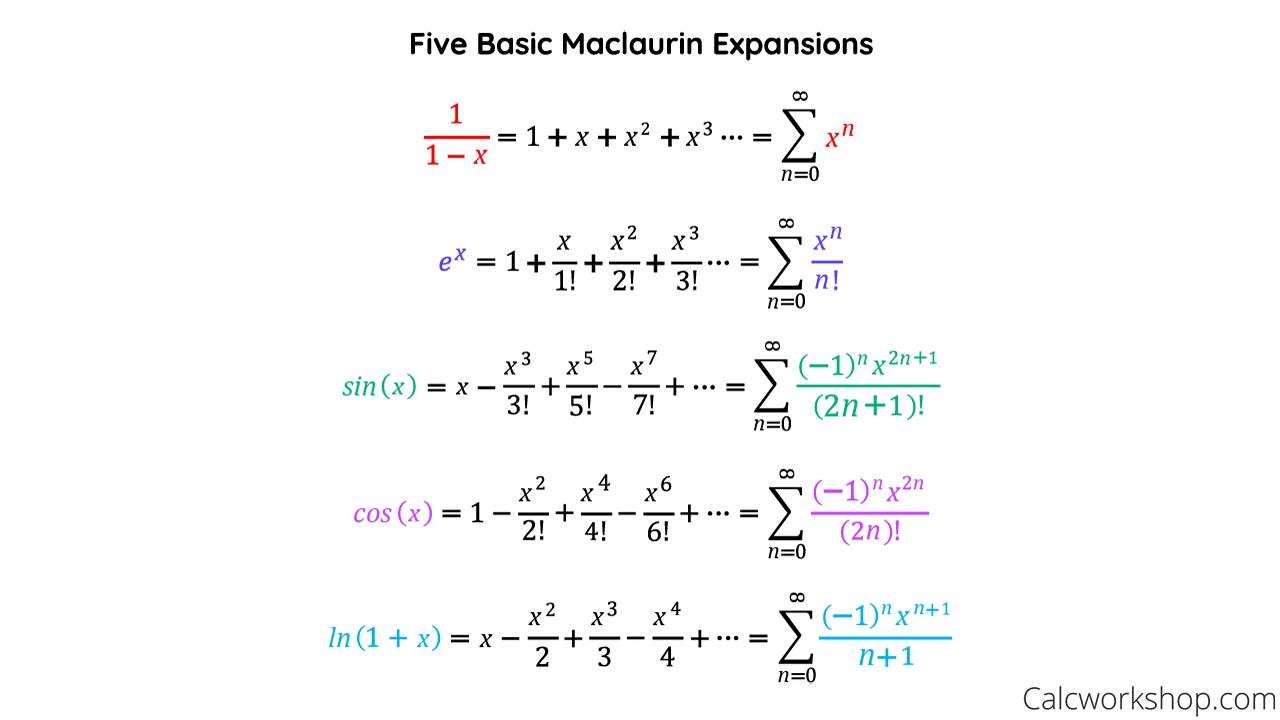

$$sin(x) = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!} + \dots$$

Look at that first term: $x$. For very small angles, $sin(x)$ is basically just $x$. Engineers call this the "Small Angle Approximation." If you’re building a pendulum clock, you don't need the complex stuff. You just use $x$. But as the angle gets wider, the error grows. The curve of the sine wave starts to pull away from that straight diagonal line. That’s where the $-\frac{x^3}{6}$ comes in. It "bends" the line back toward the curve.

It's a tug-of-war.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way to the Apple Store Freehold Mall Freehold NJ: Tips From a Local

Each new term in the series acts like a correction. The third power bends it once. The fifth power gives it another wiggle. By the time you get to the seventh or ninth power, the polynomial is hugging that sine wave so tightly you can’t even see the gap. It’s spooky.

Why the Factorials Matter So Much

You’ll notice those denominators grow fast. $3!$ is only 6, but $7!$ is 5,040. By the time you hit $11!$, you’re at nearly 40 million. This is why the series is so efficient. Because the denominator gets huge so quickly, the later terms become tiny. Fast.

If you are calculating a bridge's structural load, you might only need three terms. The fourth term is so small it wouldn't even move a needle. That’s the beauty of it. You get "good enough" results with almost zero effort.

Where the Taylor series of sin Actually Lives

Most people assume this is just for textbooks. Wrong.

Digital Signal Processing (DSP) is the backbone of the 21st century. When you record a voice memo, your phone is chopping sound waves into bits. To reconstruct or manipulate those waves, the software frequently uses approximations derived from the Taylor series of sin. It’s the same story with "Floating Point" math in CPUs. Hardware manufacturers like Intel or ARM bake these approximations directly into the silicon logic.

They use a variation called CORDIC sometimes, but the Taylor expansion remains the conceptual gold standard for understanding how we turn "curvy" reality into "flat" digital logic.

👉 See also: Why the Amazon Kindle HDX Fire Still Has a Cult Following Today

Even in video games.

When a character in Cyberpunk 2077 or Call of Duty moves their arm, the engine calculates the rotation. Rotation is all sines and cosines. If the engine had to calculate a "perfect" sine every time, your frame rate would tank. Instead, it uses fast approximations.

The Radius of Convergence Myth

Some people think Taylor series are perfect. They aren't.

In theory, the Taylor series for sine converges for every real number. You could plug in $x = 1,000,000$ and it would eventually work. But in practice? It’s a disaster. If you try to calculate $sin(100)$ using the series centered at zero, you’d need dozens and dozens of terms because the $x^n$ part grows way faster than the factorial for a long time.

This is why we use "range reduction."

Since sine repeats every $2\pi$, we just subtract $2\pi$ until the number is small. Then we let the Taylor series do the heavy lifting. It’s a tag-team effort between trigonometry and power series.

✨ Don't miss: Live Weather Map of the World: Why Your Local App Is Often Lying to You

A Real-World Example: The Great 19th Century "Computer"

Before microchips, "computers" were people. Literally.

People like Katherine Johnson (of Hidden Figures fame) or the human computers at the Harvard Observatory spent their lives filling ledgers with these calculations. They used the Taylor series of sin to create the very tables that sailors used to navigate the oceans.

If you got a term wrong, a ship might hit a reef.

The precision of these series allowed for the creation of the first reliable nautical almanacs. We essentially mapped the world using the odd-powered exponents of a polynomial. It’s wild to think that the same math used to guide a wooden ship in 1850 is now guiding a SpaceX Falcon 9.

How to Actually Use This (Actionable Insights)

If you're a student or a coder, don't just stare at the formula. Try this:

- Code it yourself: Write a simple Python loop that calculates the sine of 0.5 using 1, 2, and 3 terms. Compare it to the math library. You’ll see the error drop to almost zero by the third term.

- Visualize the "Wiggle": Use a graphing tool like Desmos. Plot $y = sin(x)$, then start plotting $y = x$, then $y = x - \frac{x^3}{6}$. Watch how the polynomial "grows" onto the sine wave. It’s the best way to understand convergence.

- Check your hardware: If you’re into embedded systems (like Arduino), look at how they handle

sin(). They often use lookup tables combined with linear interpolation—a "poor man's" Taylor series—to save memory.

Stop thinking of the Taylor series of sin as a math problem to be solved. See it as a tool for simplification. It’s the bridge between the analog world of waves and the digital world of numbers. Mastering it isn't about passing a test; it's about understanding the language of simulation.

Next time your GPS tells you exactly where you are, remember that it's just adding up a bunch of fractions with big denominators. It’s simple. It’s elegant. It works.