You’d think we’d be done with them by now. Honestly, with smartphones that have triple-mic arrays and cloud-based AI transcription, the idea of carrying a dedicated tape recorder with microphone seems like a nostalgic glitch. It’s almost 2026, yet if you walk into a serious journalism briefing or a high-end music studio, you’re going to see them. People are ditching their iPhones for physical buttons and magnetic hiss. It isn’t just about hipster aesthetics. It’s about the fact that your phone is a distraction machine, whereas a dedicated recorder is a tool.

Analog is back, but it’s different this time. We aren’t just talking about those clunky Shoebox recorders from the 80s, though those are selling for a premium on eBay right now. We’re talking about the tactile reliability of a device that doesn't drop a recording because you got a FaceTime notification or because your storage hit a limit mid-interview.

👉 See also: The 13 inch notebook bag: Why we keep buying the wrong size

The weird physics of why a tape recorder with microphone sounds "better"

Digital audio is technically perfect. That is exactly its problem. When you record a voice on a modern smartphone, the software is doing a thousand things you didn't ask it to do. It’s compressing the dynamic range. It’s "cleaning" the background noise using aggressive algorithms that sometimes make human voices sound like they’re underwater.

Tape is different.

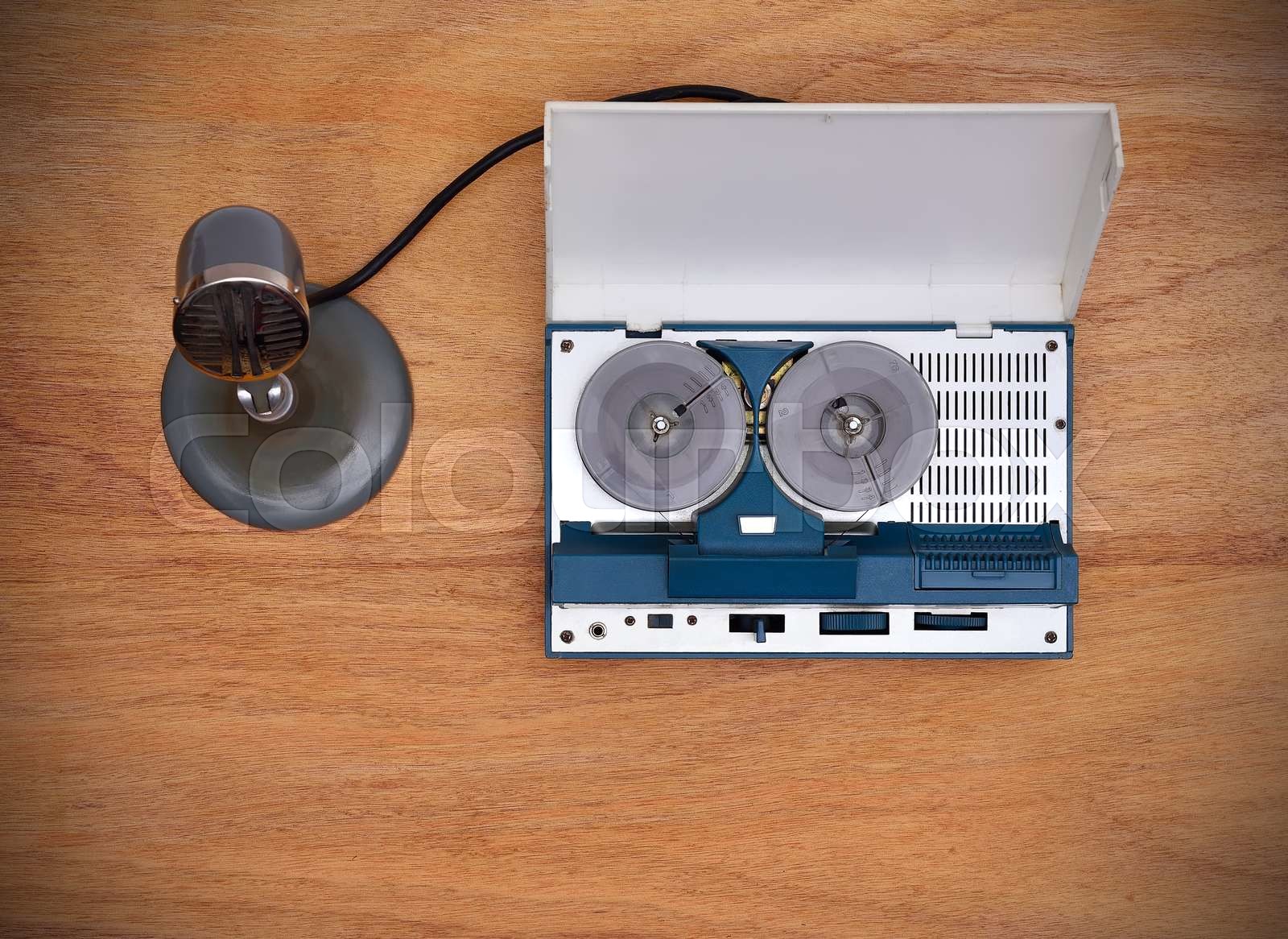

When sound waves hit the diaphragm of a microphone connected to a tape deck, they are converted into electrical signals that physically rearrange magnetic particles on a plastic ribbon. This process introduces something called tape saturation. It’s a subtle distortion that our ears perceive as "warmth." For singer-songwriters or podcasters looking for a specific "lo-fi" grit, there is no plugin that truly mimics the way a Marantz PMD-221 handles a vocal peak.

The microphone matters just as much as the tape. Most vintage-style recorders come with built-in condenser or dynamic mics, but the real magic happens when you use the 3.5mm or XLR input. Pro-grade setups often pair a high-output ribbon mic with a portable cassette deck. It sounds counterintuitive. Why put a $500 mic into a $50 recorder? Because the "limitations" of the tape act as a natural compressor. It rounds off the harsh edges of sibilant "s" sounds and adds a weight to the low end that digital often misses.

Choosing between integrated and external mics

You've basically got two paths here.

Most consumer-grade units—think the classic Sony TCM series—have a tiny hole on the front. That’s your internal mic. It’s fine for notes to self. It’s terrible for music. If you’re serious, you need a unit with a dedicated mic jack. This allows you to distance the microphone from the motor. A common complaint with the cheap tape recorder with microphone setups is the "whirring" sound. That’s the motor. If the mic is an inch away from the gears, you’re recording the machine, not the music.

Why journalists are terrified of digital-only recording

Security is a huge, often overlooked factor.

In an era of deepfakes and cloud hacks, a physical cassette is an "air-gapped" storage device. You can’t hack a piece of plastic sitting in a safe. Investigative journalists working in sensitive regions often prefer a tape recorder with microphone because it leaves no digital footprint. There’s no metadata. No GPS coordinates embedded in the file. No "last modified" timestamp that can be altered by a system update.

There’s also the psychological aspect of the "Rec" button. When you push down a physical button and hear that mechanical clunk, the interview changes. It feels official. I’ve talked to reporters who swear that sources are more honest when they see the reels spinning. It creates a sense of "the record" that a glass screen just doesn't command.

The legendary models you should actually look for

If you're hunting on the secondhand market, ignore the cheap "new" recorders sold on big-box retail sites. Those are usually mono-only with terrible plastic gears that will eat your tapes within a week. Instead, look for these:

- Sony WM-D6C (The Walkman Professional): This is the holy grail. It’s roughly the size of a thick paperback book but has better audio specs than many modern digital interfaces. It uses a quartz-locked disc drive system, meaning the speed never wavers.

- Marantz PMD series: These were the workhorses of the 90s. They are rugged. You could probably drop one down a flight of stairs and still finish your recording. They often feature "half-speed" modes, allowing you to cram twice as much audio onto a single 90-minute tape.

- Tascam Portastudio: While technically a multi-track mixer, these are the ultimate tape recorders. They allow you to plug in multiple microphones and layer sounds.

Technical hurdles: The "Hiss" and how to kill it

Let's be real: tape isn't perfect. If you buy a tape recorder with microphone, you are going to deal with noise floor issues.

Basically, every tape has a baseline level of static. In the industry, we call this "hiss." Back in the day, companies like Dolby developed "Noise Reduction" (Dolby B, C, and S). These systems essentially boosted the high frequencies during recording and then turned them back down during playback, burying the hiss in the process.

If you’re recording a podcast on tape, you need to understand signal-to-noise ratio. You want your input signal (the voice) to be as loud as possible without "peaking" or distorting. This keeps the voice far above the level of the hiss. If you record too quietly, when you turn the volume up later, the hiss will be just as loud as the person talking. It’s a balancing act. It requires actual skill, unlike digital where you can just "fix it in post."

Maintenance is a lost art

You can't just buy a 30-year-old recorder and expect it to work perfectly.

Rubber perishes. Over time, the belts inside these machines turn into a sticky, tar-like goo. If you buy a vintage unit, you’ll likely need to replace the belts. It's a fiddly job involving tweezers and a lot of patience.

Then there’s the "head." The recording head is the part that actually touches the tape. It’s a magnet. Over time, it gets dirty with brown oxide dust. If your recordings sound muffled, like there’s a blanket over the speakers, your head is dirty. A Q-tip dipped in 91% isopropyl alcohol is the standard fix. Don't use 70%—the water content is too high and can cause rust.

You also need to "demagnetize" the heads occasionally. If the metal parts of the recorder become accidentally magnetized, they will actually start erasing the high frequencies of any tape you play. It sounds like science fiction, but it’s just physics.

The cost of the "Analog Tax"

Is it expensive? Sorta.

A pack of five high-quality Type II (Chrome) cassettes can set you back $50 or more because they aren't mass-produced like they used to be. Most "new" tape you find today is Type I (Ferric). It’s fine for voice, but it lacks the frequency response for high-fidelity music.

You also have to consider the digitizing process. Unless you plan on only listening to your tapes on a Walkman, you’ll eventually need to plug your recorder into a computer to share the audio. This requires a decent sound card or a USB interface.

Practical Next Steps for Enthusiasts

If you are ready to dive into the world of magnetic media, do not start by buying a $500 professional deck.

🔗 Read more: The 3D Printed Liberator Pistol: What Most People Get Wrong About the Gun That Changed Everything

Start small. Find a functional, mid-range Sony or Panasonic portable recorder at a thrift store or a garage sale. Look for the "Made in Japan" label; those usually have superior internal components compared to later models.

First, test the motor. Put in a tape you don't care about and see if it plays at a consistent speed. If it sounds like the person is talking underwater or in slow motion, the belts are slipping.

Second, check the battery compartment. Leaking alkaline batteries are the #1 killer of vintage electronics. If you see white crusty powder on the springs, you’ll need to clean it with vinegar and a toothbrush before the unit will even power on.

Third, get a decent external microphone. Even a basic $20 lavalier mic plugged into the "Mic In" jack will sound significantly better than the built-in microphone.

Once you have your gear, embrace the constraints. The beauty of a tape recorder with microphone is that you can't hit "undo." You can't edit out every "um" and "ah" with a mouse click. It forces you to be present. It forces you to get the take right the first time. In 2026, that kind of intentionality is the rarest commodity in the world.

Stop worrying about bitrates and start listening to the texture of the sound. Grab a Maxell XL-II, hit those two buttons simultaneously, and wait for the click. There is nothing else like it.