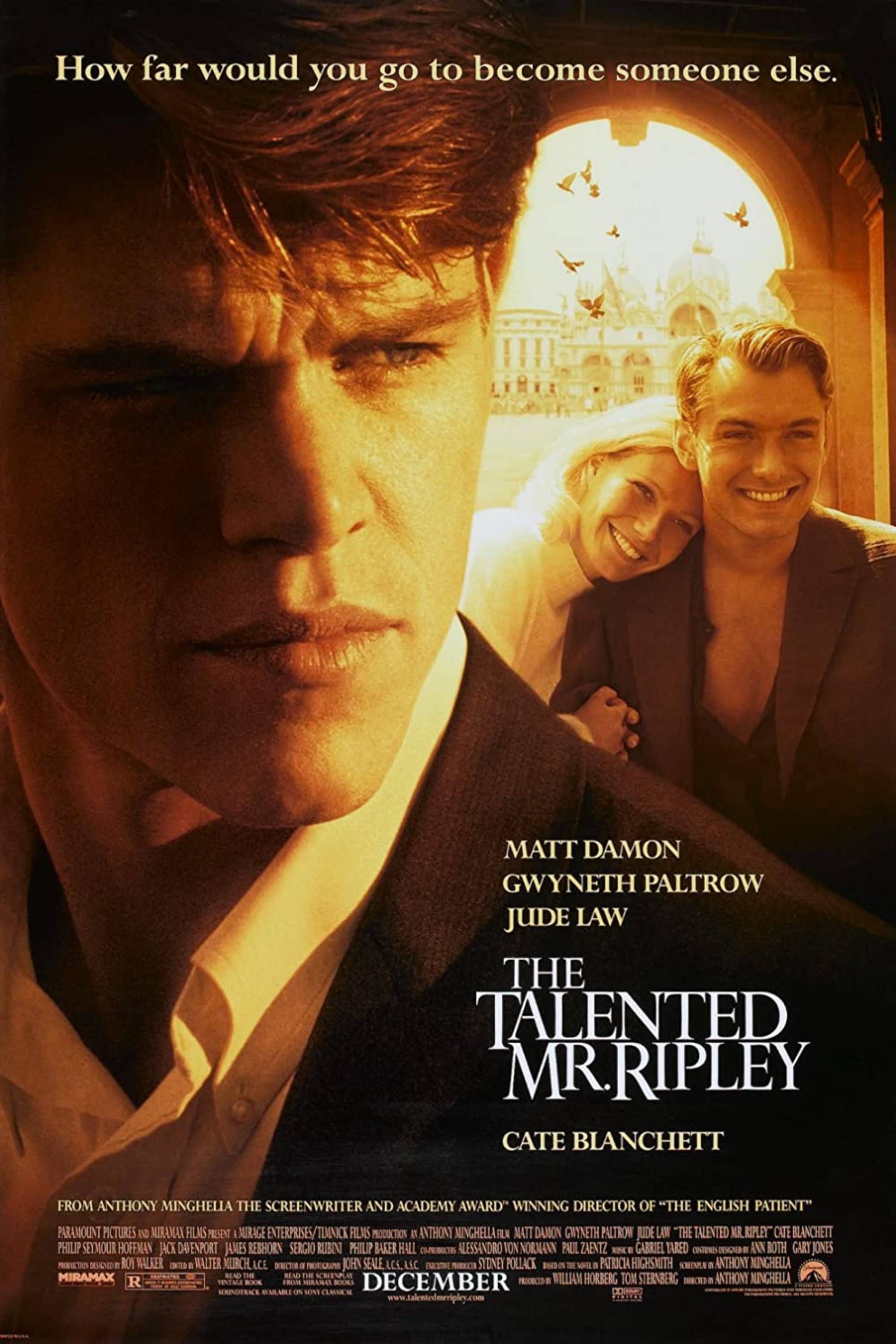

Anthony Minghella’s 1999 masterpiece The Talented Mr. Ripley is a movie that shouldn't feel this modern. It’s a period piece. It’s set in the 1950s. Everyone is wearing high-waisted trousers and listening to jazz records that are now seventy years old. Yet, every time I rewatch it, I’m struck by how it perfectly captures the specific, itchy anxiety of the social media age. It’s a film about curation. It’s about looking at someone else’s life—their sun-drenched Italian villa, their perfect linen shirts, their effortless charisma—and deciding that you would rather be a "fake somebody than a real nobody."

Tom Ripley is the original "stan" gone wrong.

Most people remember the movie for the aesthetics. The cinematography by John Seale is breathtaking, turning the Italian coast into a lush, saturated dreamscape that feels almost too beautiful to be real. And that’s the point. We are seeing Italy through Tom’s eyes. He’s an outsider looking through a window, and once he gets a taste of the interior, he’ll do anything to stay there. Honestly, it's terrifying how relatable that feels. We all curate our lives now. We all pick the best filters. Tom just took the logic of "fake it 'til you make it" to its most violent, logical extreme.

The Talented Mr. Ripley and the Horror of Being Seen

The movie starts with a lie of convenience. Tom, played with a twitchy, desperate brilliance by Matt Damon, is mistaken for a Princeton grad by a wealthy shipbuilder. Instead of correcting him, Tom leans in. He accepts a mission to travel to Italy and retrieve the man's son, Dickie Greenleaf.

🔗 Read more: The O.C. Cast Season 2: Why the New Faces Almost Ruined Newport (and Saved It)

Here is where the movie gets complicated. Jude Law’s performance as Dickie is perhaps the most important thing in the film. He’s magnetic. He’s the sun, and everyone else is just a planet orbiting his ego. But as soon as you stop being interesting to him, he turns cold. He shuts you out. For someone like Tom, who has nothing and is effectively "nobody" back in New York, that coldness is a death sentence.

The turning point in the boat—that scene in San Remo—is one of the most uncomfortable sequences in cinema history. It’s not just the violence. It’s the rejection. Dickie tells Tom he’s a "bore." In the world of The Talented Mr. Ripley, being boring is a far greater sin than being a criminal. When Tom strikes Dickie with that oar, he isn't just killing a man; he’s trying to kill the part of himself that Dickie despised. He wants to step into Dickie’s skin. He wants the rings, the clothes, and the privilege that comes with never having to say "thank you" or "sorry."

The sheer genius of the casting

Look at the lineup. It’s insane. You have Gwyneth Paltrow as Marge, the only person who actually sees Tom for what he is. You have Cate Blanchett as Meredith Logue, a character Minghella added to the story who serves as a mirror for Tom’s lies. And then there’s Philip Seymour Hoffman as Freddie Miles.

Freddie is the absolute worst. He’s loud, he’s arrogant, and he’s incredibly perceptive. He smells the "cheapness" on Tom instantly. The scene where Freddie walks into the apartment and realizes something is wrong is a masterclass in tension. He’s the only one who can’t be fooled by Tom’s soft-spoken act because Freddie understands the specific language of wealth that Tom is trying to mimic. He knows Tom doesn't belong. He says it with his eyes before he ever says it with his mouth.

Why this isn't just a standard thriller

In most thrillers, we want the killer to get caught. In The Talented Mr. Ripley, Minghella does something much more cruel to the audience: he makes us complicit. Because Tom is our protagonist, and because we see how much he's been looked down upon by people like Dickie and Freddie, a tiny, dark part of us wants him to get away with it.

We hold our breath when the police are at the door. We cringe when Tom almost slips up his accent. It’s a deeply manipulative piece of filmmaking. It forces you to confront your own class resentments.

The ending of the film departs significantly from Patricia Highsmith’s original 1955 novel. In the book, Tom is much more of a cold-blooded sociopath. In the movie, he feels like a wounded animal. The final scene on the ship, involving Peter Smith-Kingsley (played with heartbreaking warmth by Jack Davenport), changes everything. In the book, Tom wins. In the movie, Tom "wins" but he has to murder the only person who actually loved him for who he really was. He ends up in a dark cabin, literally and figuratively alone. He has the money and the status, but he has had to "shut the door" on his own soul to keep it.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Paul McCartney Michael Jackson Songs

Nuance in the Adaptation

Critics often argue about whether the movie "softened" Ripley too much. Some Highsmith purists think Damon’s version is too sympathetic. I disagree. Making him human makes him scarier. If he’s just a monster, he’s a caricature. If he’s a guy who just wanted to be loved and let his envy turn into a cancer, that’s something that could happen to anyone. Sorta.

The film also explores queer subtext in a way that was quite bold for 1999. Tom’s obsession with Dickie isn't just about his lifestyle; it's about a repressed desire that Tom doesn't have the tools to express. When Dickie mocks that desire, the explosion of violence feels inevitable. It’s a tragedy of identity. Tom doesn't know who he is, so he becomes everyone else.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Cinephiles

If you’re looking to dive deeper into the world of Tom Ripley or just want to appreciate the movie on a more technical level, here are a few things to do.

First, watch the 1960 French adaptation, Purple Noon (Plein Soleil). It stars Alain Delon as Tom. Delon’s Ripley is entirely different—he’s cool, calculated, and dangerously handsome. Comparing Damon’s desperate Ripley to Delon’s icy Ripley is a fascinating exercise in how much a lead actor can change the DNA of a story.

📖 Related: Who Killed the President in Paradise and Why the Ending Still Divides Fans

Second, pay attention to the sound design next time you watch the 1999 film. The transition from the chaotic, loud jazz clubs to the quiet, ticking silence of the apartments Tom inhabits is intentional. The music moves from the "hot" jazz of Dickie’s world to the more somber, classical compositions that represent Tom’s isolation. Gabriel Yared’s score is doing a lot of the heavy lifting emotionally.

Third, read the actual book. Patricia Highsmith was a master of "amoral" fiction. She doesn't judge Tom. She just observes him like a scientist watching a microbe. It’s a chilling read because it lacks the lush romanticism of the movie. It’s dry, sharp, and mean.

Finally, look at the clothes. Costumes by Ann Roth and Gary Jones weren't just about looking "vintage." The transition of Tom's wardrobe from ill-fitting corduroy to bespoke Italian tailoring tracks his moral decay. The better he looks, the worse he becomes.

The Talented Mr. Ripley remains a staple of cinema because it refuses to give us an easy out. It doesn't offer a moral lesson or a neat resolution. Instead, it leaves us in that dark basement of the mind, wondering just how much of ourselves we’d be willing to trade for a life that looks better in a frame.

To truly appreciate the layers of this story, start by watching Purple Noon to see the contrast in characterization. Then, track the use of "mirrors" throughout Minghella's film; Tom is almost always seen in a reflection or through glass, symbolizing his fractured identity. If you want to understand the psychological roots of the character, read Highsmith's Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction—it reveals how she crafted a protagonist that audiences would root for despite his heinous actions.