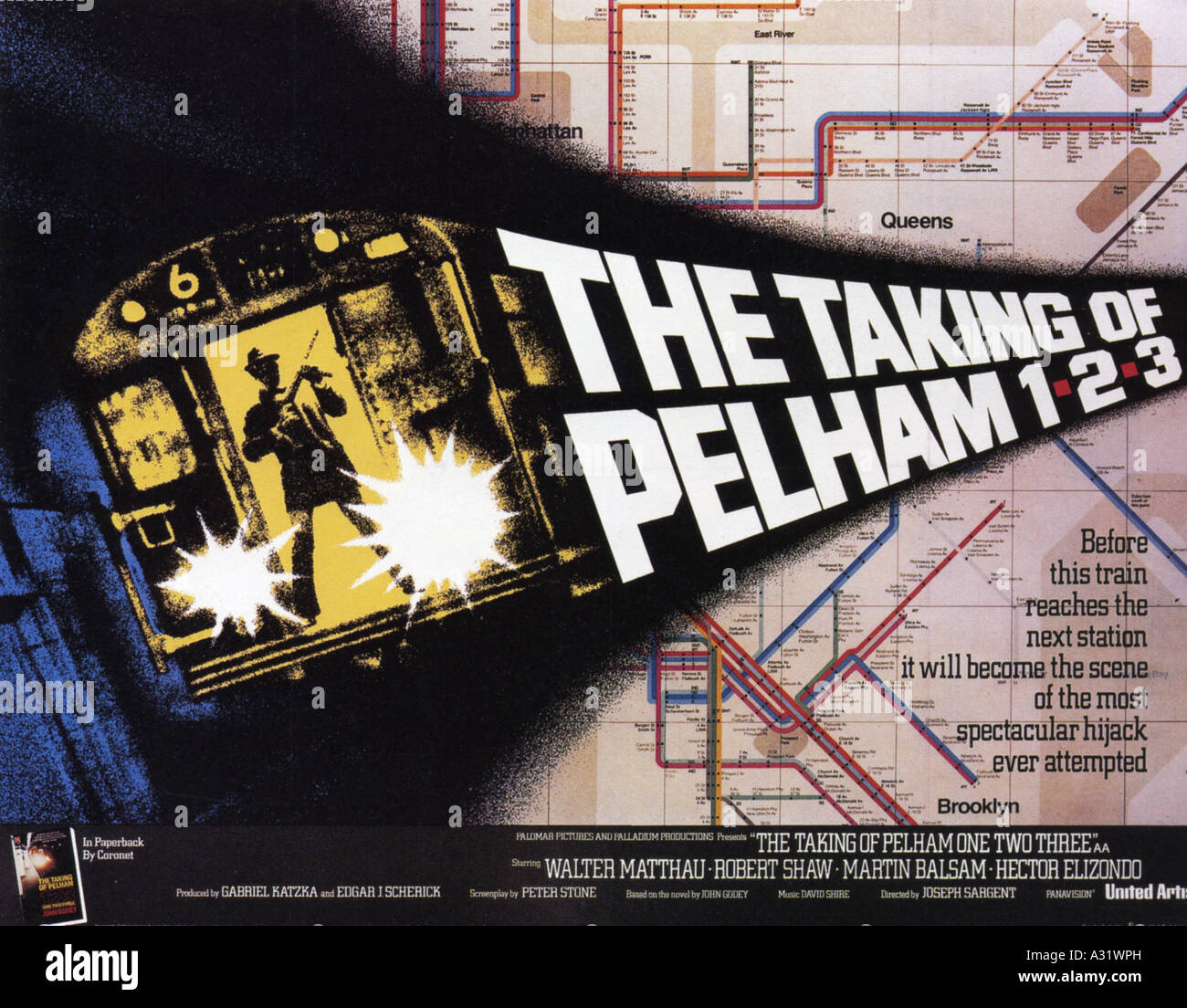

New York City in the seventies was a mess. It was grimy, broke, and loud. If you want to see exactly what that felt like without actually stepping into a time machine, you watch The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974). Honestly, it’s the meanest, leanest thriller ever shot in the Five Boroughs. Forget the 2009 remake with Denzel Washington and John Travolta—it’s fine, but it lacks the sweat. The original movie is a masterclass in tension, and it basically invented the "color-coded" criminal trope long before Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs hit the scene.

The premise is deceptively simple. Four men board a southbound subway train at 59th Street. They’re armed. They’re professional. They take the passengers hostage and demand $1 million from the city of New York. If they don't get the cash in an hour, they start killing one person for every minute the money is late. It’s a ticking clock that feels like a sledgehammer.

The Gritty Reality of Pelham 123

You’ve got to understand the context of the era. 1974 was a weird time for movies. Cinema was moving away from the polished studio look and into something way more cynical. Director Joseph Sargent didn't want a "movie" version of the subway. He wanted the real thing. He actually filmed in the New York City transit system, specifically on the abandoned Court Street station in Brooklyn (now the Transit Museum) and on the tracks of the IND line.

The grit is real.

The air in those tunnels looks thick enough to choke on. Walter Matthau, playing Lt. Zachary Garber, looks like he just woke up in a rumpled suit and hasn't had a good cup of coffee in three years. That’s the magic of Matthau. He isn’t an action hero. He’s a guy who works for the Transit Authority. He’s got a job to do, and that job happens to involve negotiating with a cold-blooded mercenary played by Robert Shaw.

Shaw is Mr. Blue. He’s terrifying because he’s so calm. While the city is screaming and the police are fumbling with logistics, Mr. Blue is checking his watch. It’s a collision of two very different types of New York energy: the bureaucratic chaos of the city government and the surgical precision of the hijackers.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the 1974 version hits differently

Most modern thrillers rely on CGI or hyper-kinetic editing. Pelham 123 (1974) relies on faces. Seriously. The casting of the hostages is incredible. You have a cross-section of New York—the cranky old man, the hippie, the terrified mother—all stuck in a metal tube. It feels claustrophobic because it is.

And then there's the score.

David Shire’s soundtrack is a jagged, brass-heavy jazz nightmare. It doesn't underline the emotion; it drives the anxiety. It sounds like the city itself is screaming. It’s arguably one of the most effective scores in the history of crime cinema. If you haven't heard it, go find the main theme on Spotify right now. It'll make you feel like you're being chased through a dark alley.

Breaking Down the Heist Mechanics

The hijackers are Mr. Blue (Shaw), Mr. Green (Martin Balsam), Mr. Grey (Hector Elizondo), and Mr. Brown (Earl Hindman). They aren't friends. They don't even like each other. That creates a layer of internal friction that most heist movies skip. Mr. Grey is a loose cannon who was kicked out of the mafia for being too violent. Think about that for a second.

The plan relies on the "dead man's feature" on the train. Basically, the train won't move unless someone is physically holding the throttle. This is a crucial plot point that keeps the police from just storming the car. The movie treats the mechanics of the subway with total respect. It’s a procedural. You learn how the power grids work, how the dispatchers communicate, and how the "123" in the title actually refers to the time the train left the Pelham Bay Park station.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

The Matthau Factor

Walter Matthau was known for comedies like The Odd Couple, so seeing him here is a bit of a shock if you aren't familiar with his 70s crime run (see also: The Laughing Policeman). He brings this weary, sardonic wit to the role. When he’s told the hijackers want a million dollars, his reaction isn't "Oh no, lives are at stake," it's more like, "In this economy? For a subway train?"

He represents the resilience of New Yorkers. The city is falling apart, the Mayor is sick in bed with the flu and more worried about his approval ratings than the hostages, and the police are stuck in traffic. Garber is the only one keeping it together.

The dialogue, written by Peter Stone (who adapted John Godey’s novel), is sharp. It’s fast. People talk over each other. They insult each other. It’s incredibly human. There’s a scene where Garber is showing some visiting Japanese transit officials around the command center just as the hijacking starts. It adds this layer of dark comedy that makes the violence feel even more jarring when it actually happens.

The Legacy and the "Tarantino Connection"

People often talk about how Quentin Tarantino borrowed the color-coded names for Reservoir Dogs. He’s been pretty open about it. But the influence of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three goes deeper than just names. It’s about the "professionalism" of the criminals. These aren't mustache-twirling villains. They are men with a spreadsheet.

The ending—and don't worry, I won't spoil the very last frame—is one of the most perfect "gotcha" moments in cinema history. It’s subtle, hilarious, and completely earned. It’s the kind of ending that makes you want to immediately rewind the movie to see if you missed the setup. (You didn't, it’s just that well-placed).

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Realism Over Spectacle

In the 2009 remake, there are car chases and massive explosions. The 1974 original doesn't need that. The most intense scene in the movie involves a man walking a bag of money across a street. That’s it. But because the stakes are so clearly defined, it feels like the most important thing in the world.

The movie also doesn't shy away from the politics of the time. The Mayor is portrayed as a total weakling. He’s terrified of the voters. He only agrees to pay the ransom when his advisor tells him it’ll make him look like a hero. It’s a cynical view of leadership that felt very relevant in the post-Watergate era.

If you're a fan of Heat, Inside Man, or Dog Day Afternoon, you owe it to yourself to watch this. It is the blueprint.

How to watch and what to look for

If you're going to dive into this classic, keep an eye out for these specific details that make the movie a masterpiece:

- The Wardrobe: Notice how Robert Shaw’s Mr. Blue is dressed in a crisp trench coat and hat. He looks like a businessman. Contrast that with Matthau’s yellow shirt and mismatched tie. It tells you everything about their characters.

- The Sound Design: Listen to the background noise in the transit command center. The clicking of the tiles, the phones ringing, the distant rumble of trains. It’s immersive.

- The Pace: The movie is only 104 minutes long. It doesn't waste a single second. Every scene moves the plot forward or builds the world.

For those interested in the technical side, the film was shot by Owen Roizman, the same cinematographer who did The French Connection and The Exorcist. He knew how to make New York look dangerous and beautiful at the same time.

Actionable Next Steps

To truly appreciate the 1974 version of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, don't just stream it on a laptop. This is a movie built for a big screen or at least a high-quality home setup where you can hear the score properly.

- Find the Original: Ensure you are watching the 1974 version directed by Joseph Sargent. Many streaming platforms will suggest the 2009 remake first.

- Listen to the Score First: Search for David Shire's "Main Title" on YouTube. It sets the mood perfectly before the first frame even appears.

- Read the Book: John Godey’s 1973 novel is a fantastic read and provides even more internal monologue for the hijackers.

- Double Feature: Pair it with Dog Day Afternoon (1975) for the ultimate "74-75 New York in Crisis" cinematic experience.

This film remains a pinnacle of the heist genre because it understands that the most interesting part of a crime isn't the gunfight—it's the people involved and the city they’re trying to rob. It’s a snapshot of a New York that doesn't exist anymore, captured perfectly on 35mm film.