Florida is mostly flat. You know that. It's basically a giant limestone pancake with some palm trees stuck in it. Because it’s so flat, water usually doesn't know where to go, but the St Johns River Florida is different. It’s weird. It’s one of the few lazily drifting rivers in the world that flows north. People will tell you it's because the "north sucks," which is a classic Jacksonville joke, but the reality is much more interesting and a little bit fragile.

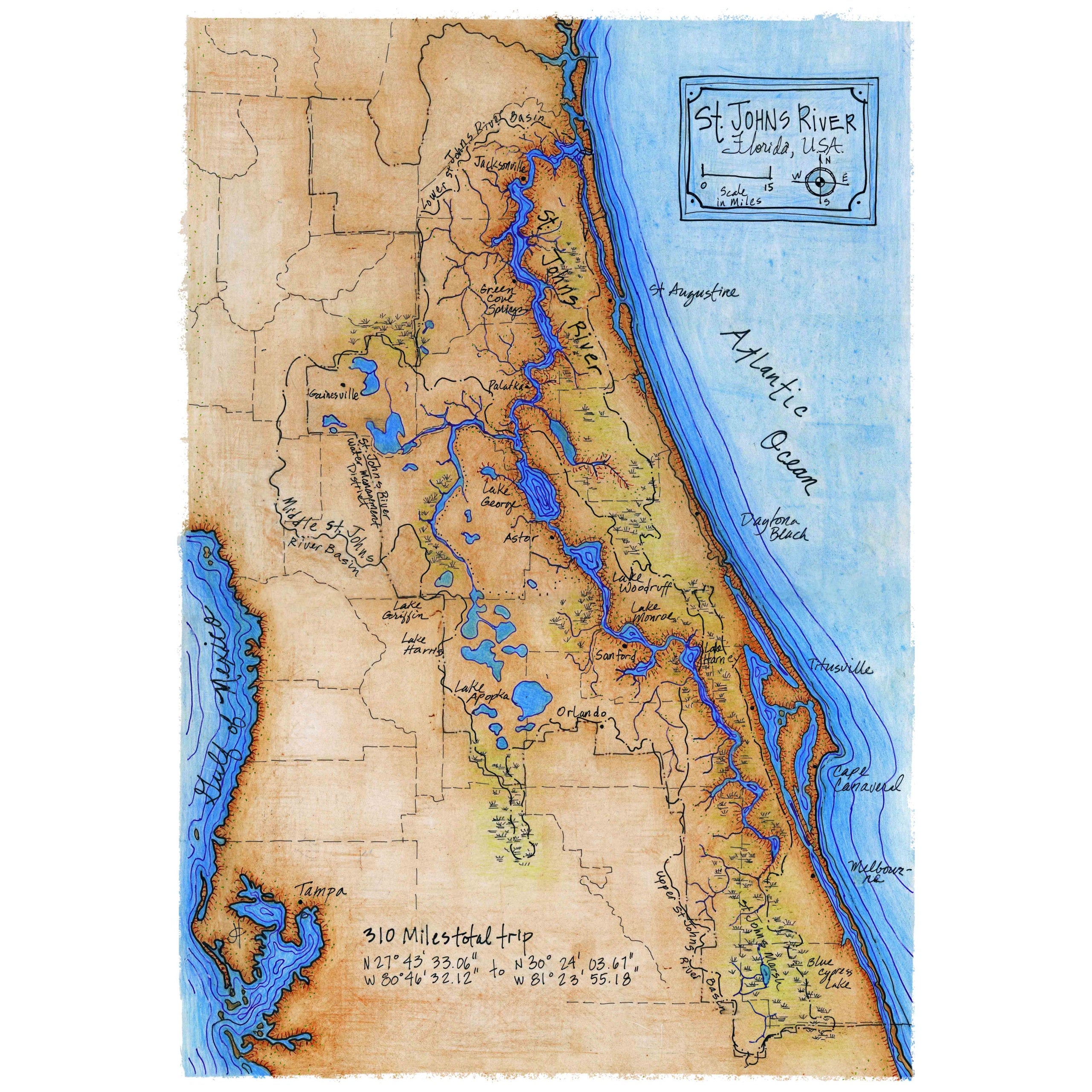

It starts in the marshes of Indian River County. Just a slow, seeping collection of wetlands. From there, it crawls 310 miles up the coast to Mayport. It only drops about 30 feet in elevation over that entire distance. That is an average slope of about one inch per mile. Think about that. If you drop a leaf in the water in Melbourne, it takes a lifetime to reach the Atlantic.

The St Johns River Florida is actually an elongated lagoon

Most people call it a river. Geologically? It’s basically a series of connected lakes. Because the gradient is so insanely low, the tide from the Atlantic Ocean can actually push salt water dozens of miles inland. This creates a "brackish" nightmare for some species and a paradise for others. You’ve got manatees swimming right alongside sharks sometimes. It’s a mess of biodiversity that shouldn't work, but it does.

If you’re out on the water near Blue Spring State Park, the water is crystal clear and 72 degrees year-round. But by the time that same water reaches Palatka, it looks like strong tea or root beer. That’s not "dirt." It’s tannins. The decaying vegetation in the swamps leaches organic acids into the water. It’s perfectly natural, though it makes the river look intimidatingly deep and dark.

I’ve seen people terrified to jump in because they can't see their feet. Honestly, they probably shouldn't jump in anyway—not because of the water quality, but because of the residents. Alligators are a given, but it’s the sheer scale of the ecosystem that catches people off guard.

The Manatee Factor and Winter Survival

The St Johns River Florida acts as a massive thermal blanket for Florida’s most famous residents. When the Atlantic drops below 68 degrees, manatees start dying. They get "cold stress," which is basically hypothermia for sea cows. They flock to the springs that feed the St Johns.

- Blue Spring: On a cold January morning, you can see 700+ manatees huddling together.

- Silver Springs: Further off but connected through the Ocklawaha, the entire system is a life-support machine.

It’s a sight that honestly changes how you view the state. Florida isn't just theme parks; it's this ancient, slow-moving pulse.

✨ Don't miss: Weather Las Vegas NV Monthly: What Most People Get Wrong About the Desert Heat

Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and the Fight for the Basin

We have to talk about the green stuff. Not the trees—the algae. The St Johns River Florida is struggling. Because it moves so slowly, any pollution we dump into it just sits there. It doesn't "wash away." It festers.

Runoff from fertilized lawns in Orlando and industrial farms further south pumps nitrogen and phosphorus into the basin. When the sun hits that stagnant, nutrient-rich water in the summer, you get cyanobacteria blooms. It looks like bright green pea soup. It’s toxic to dogs, it kills fish, and it smells like a dumpster behind a seafood restaurant.

The St Johns Riverkeeper, an advocacy group currently led by Lisa Rinaman, has been screaming about this for years. They've fought against "surface water withdrawals." That’s a fancy term for cities trying to suck water out of the river to water lawns in the suburbs. If you take the water out, the river flows even slower. If it flows slower, the salt water from the ocean creeps further south.

Why the "Flow" matters for your backyard

If the salt wedge moves too far south, it kills the cypress trees. Cypress trees can handle wet feet, but they can't handle salt. Once the trees die, the shoreline erodes. Once the shoreline erodes, the houses built on the river start sliding into the muck. Everything is connected.

- The aquifer provides our drinking water.

- The river recharges the aquifer.

- The trees stabilize the river.

- The salt kills the trees.

It’s a domino effect that most people living in Jacksonville or Sanford don't think about until their dock is underwater or their favorite fishing hole is a dead zone.

Exploring the River: From Airboats to Houseboats

If you want to actually see the St Johns River Florida, don’t go to Jacksonville first. Jacksonville is where the river is widest—nearly three miles across in some spots—and it feels more like a bay. It’s industrial. It’s big bridges and shipping containers.

🔗 Read more: Weather in Lexington Park: What Most People Get Wrong

Instead, go to Hontoon Island. You can only get there by boat. It’s a park that feels like you’ve stepped back 1,000 years. The Timucua Indians lived here, and you can still see the shell middens—basically ancient trash heaps of snail shells that have become hills.

The river here is narrow. The trees canopy over the water. You’ll see ospreys diving for shad and maybe a bald eagle if you're lucky. If you're into fishing, this is the "Bass Capital of the World." Or at least, that's what the signs in Palatka say. The largemouth bass here are legendary because they have so many places to hide in the hydrilla and eelgrass.

The shad run is a local obsession

Every winter, American Shad migrate from the ocean up the St Johns to spawn. It’s a huge deal. Anglers come from all over the country to catch these "poor man’s salmon." It’s one of the few times the river feels truly "busy" in the rural stretches.

Realities of Living on the River

Living on the St Johns isn't all sunsets and sweet tea. It’s humidity that feels like a wet wool blanket. It’s mosquitoes the size of small birds. And it’s the constant threat of flooding.

During Hurricane Ian and later Nicole, the St Johns River Florida didn't just rise; it stayed risen. For weeks. Because the river is so flat and flows north, if a storm pushes water in from the ocean, the river water has nowhere to go. It backs up. People in places like Geneva and Astor had feet of water in their living rooms for a month.

The river has a long memory. It reclaims its floodplain whenever it wants.

💡 You might also like: Weather in Kirkwood Missouri Explained (Simply)

Actionable Steps for Visiting or Protecting the River

If you're planning to engage with this massive waterway, don't just look at it from a bridge. You need to get on the water to understand it.

How to experience it the right way:

- Rent a houseboat in Sanford: This is probably the coolest way to see the middle basin. You can live on the water for a weekend and just drift.

- Airboat tours in Christmas, FL: If you want to see the "headwaters," this is it. It’s loud, fast, and you’ll see more gators than you can count.

- Visit the Micro-Groves: Along the banks, you’ll find wild orange trees. They’re sour as lemons, but they are remnants of the old groves that used the river for transport before the railroads took over.

How to help (if you live here):

- Check your fertilizer: Use slow-release, nitrogen-free fertilizer. Better yet, don't fertilize during the rainy season (June-September).

- Support the Riverkeeper: Look up the St Johns Riverkeeper and see what legislation they are currently fighting. Usually, it involves stopping massive developments that want to pave over the wetlands that filter the river's water.

- Mind the No-Wake Zones: Manatees are slow. Boats are fast. Propeller scars are on almost every manatee in the river. Pay attention to the signs.

The St Johns River Florida is a weird, ancient, north-flowing anomaly. It’s the spine of the state. It isn't as flashy as the beaches or as famous as the Everglades, but it’s the reason people settled here in the first place. Respect the current, even if you can barely see it moving.

To get started, download the "Fish|Hunt FL" app to check local regulations and grab a map of the Bartram Canoe Trail. This trail follows the path of William Bartram, the naturalist who explored the river in the 1770s. Seeing the river through his eyes—comparing what he wrote then to what we see now—is the best way to realize how much we have to lose.

Check the water levels on the NOAA St. Johns River hydrograph before you head out, especially in the autumn months. High water can make some boat ramps inaccessible and turn a simple trip into a rescue mission. Plan your trip around the tides, even if you are 50 miles inland, because that ocean push is stronger than you think.