It’s just a color. Except, clearly, it isn't. When Bobby Vinton released the song Blue on Blue in 1963, he wasn't just singing about a palette choice or a fashion faux pas. He was tapping into a very specific, very mid-century brand of melancholy that feels almost alien in our current era of high-definition heartbreak. It’s a song about the layering of sadness—sadness upon sadness—and it basically defined the "Crooner Era" transition into the pop-rock revolution.

Honestly, the track is a bit of a trick. You hear that bouncy, jaunty Burt Bacharach and Hal David arrangement and you think, "Oh, this is a happy little tune." It's not. It’s actually pretty devastating.

The Architecture of a Heartbreak Anthem

We have to talk about Burt Bacharach. The man was a mathematical genius of melody, and with the song Blue on Blue, he and Hal David created a weirdly perfect juxtaposition. The lyrics are about a guy who is so depressed he's literally seeing the world through a cobalt lens because his girl is gone. But the music? It’s swaying. It’s catchy. It’s the kind of thing your grandmother would hum while doing the dishes, completely ignoring the fact that the narrator is essentially undergoing a psychological breakdown.

Vinton had this "Prince of Roses" persona, but his voice on this track has a specific, thin vulnerability. It isn't the booming power of Sinatra. It’s the sound of a regular guy in a suit trying to keep it together. That’s why it worked. In 1963, the song soared to number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100. It wasn't just a hit; it was a mood. People were obsessed with this idea of "blue" being more than a color. It was a physical weight.

Why "Blue" Became the Universal Language of 1963

You've probably noticed that the early 60s were obsessed with the color blue. You had "Blue Velvet" (also Vinton), "Blue Bayou," and "mister blue." But the song Blue on Blue did something different by doubling down. It wasn't just that he felt blue; he was "blue on blue," which implies a saturation point.

Think about it this way:

If you’re blue, you’re sad. If you’re blue on blue, the sadness has become your entire environment. It’s the carpet, the walls, the sky, and the skin. Hal David’s lyrics—"Blue on blue, heartache on heartache"—explicitly tell you that this is a stacking effect. It’s recursive grief.

There's a specific line that always sticks out: "I wait alone in the darkness." It’s simple. It’s blunt. In a three-minute pop song, you don't have time for T.S. Eliot levels of metaphor. You just need to tell the listener that the lights are out and nobody is coming home. Vinton delivers it with a sort of polite desperation that was very "on brand" for the Kennedy era before everything got messy and loud in the late 60s.

The Bacharach Effect and the Shift in Pop

A lot of people forget that this was a Bacharach/David composition. Before they were synonymous with Dionne Warwick, they were crafting these tight, orchestral pop nuggets for guys like Vinton and Gene Pitney. The song Blue on Blue uses a shifting rhythmic structure that makes it feel like it’s constantly moving forward, even though the lyrics are stuck in a room, mourning.

Musicologists often point to this era as the "Professional Era" of songwriting. Everything was polished. Every horn hit was calculated. But within that polish, there was a lot of room for genuine angst. You can hear the influence of this specific production style in later acts like The Carpenters. It’s that "sunny-sounding sadness" that became a staple of American radio.

Some critics back then thought Vinton was a bit too "safe." Compared to the grit of the burgeoning soul scene or the impending British Invasion, a song about being blue might have seemed quaint. But look at the charts. The public wasn't ready to let go of the crooner. They wanted someone who could articulate their loneliness without screaming it.

Common Misconceptions About the Lyrics

I’ve heard people argue that the song Blue on Blue is about a military "friendly fire" incident because that's what the term means in modern tactical jargon. Let's be very clear: It’s not. In 1963, "blue on blue" hadn't really entered the common civilian lexicon as a military term in the way it has now.

It was purely aesthetic.

It was poetic.

Another weird thing people get wrong is thinking this was a cover of an older standard. Nope. This was written specifically for the era. While Vinton did a lot of covers (like "Blue Velvet," which was a 1950s track), this one was fresh. It was built for his specific vocal range—that high, slightly pinched tenor that sounds like it’s about to crack but never quite does.

The Cultural Legacy of the Cobalt Mood

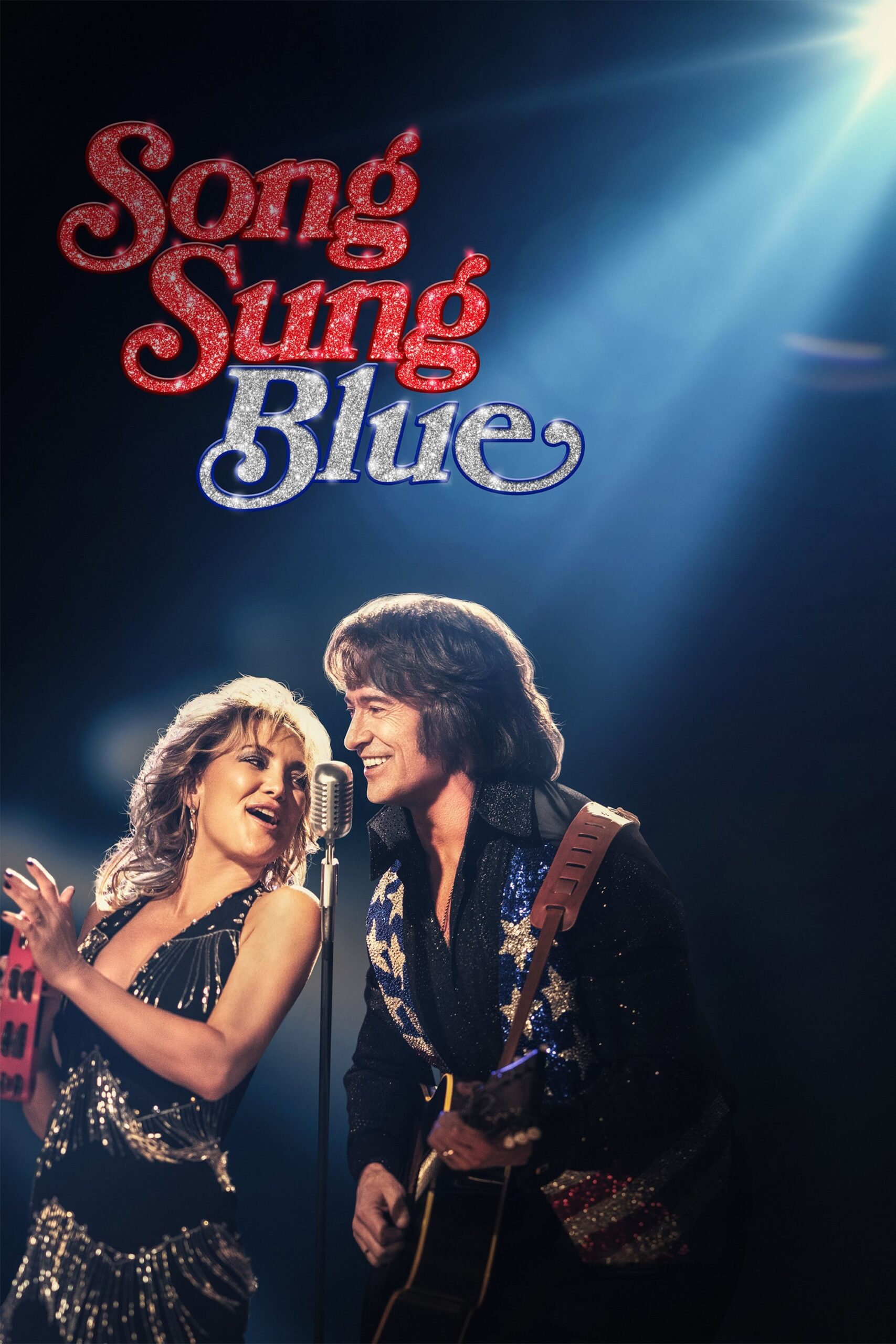

It’s fascinating how we still use this song as a shorthand for a specific type of nostalgia. If a movie director wants to signal "the early 60s but something is slightly wrong," they play the song Blue on Blue. It has that David Lynch-ian quality before Lynch even made it a thing. It’s too perfect. It’s too clean. And because it’s so clean, the sadness feels even more clinical and haunting.

If you listen to the track today on a good pair of headphones, you can hear the room. You can hear the isolation of the vocal booth. It doesn't sound like a band in a garage; it sounds like a man in a vacuum.

- The song peaked at #3 on the Billboard Hot 100.

- It spent 13 weeks on the chart.

- It was the lead-off track for an album of the same name, which was essentially a concept album about the color blue.

That album, Blue on Blue, included songs like "Blueberry Hill," "Am I Blue," and "Blue, Blue Day." Vinton basically cornered the market on sadness-based marketing. He was the king of the "Blue" brand long before the Blue Man Group or Eiffel 65 showed up.

How to Listen to Blue on Blue Like an Expert

If you want to actually appreciate what’s happening in the song Blue on Blue, you have to stop treating it like elevator music. You have to listen to the percussion. There’s a steady, almost clock-like ticking in the background of the arrangement. It’s the sound of time passing while you’re waiting for someone who isn't coming back.

👉 See also: How to Watch Independent Lens I Am Not Your Negro and Why It Still Hits So Hard

Compare it to Vinton’s other hits. "Roses are Red" is sweet and a bit juvenile. "Lonely" is operatic and big. But "Blue on Blue" is sophisticated. It’s the "adult" version of a breakup song. It acknowledges that sometimes, there isn't a big dramatic fight. Sometimes, you just sit in a room and everything looks blue.

The song actually influenced a lot of the "Baroque Pop" that would follow. When you hear the strings swell in the middle eight, that's the bridge between the Big Band era and the psychedelic era. It’s a historical pivot point disguised as a catchy radio hit.

Practical Takeaways for Your Playlist

The song Blue on Blue isn't just a relic. It’s a masterclass in how to use a limited metaphor to achieve maximum emotional impact. If you're a songwriter or just a fan of music history, there are a few things to take away from Bobby Vinton's 1963 run:

- Contradiction is Key: Pairing sad lyrics with an upbeat tempo creates "emotional friction." It makes the listener feel uneasy in a way that keeps them coming back.

- The Power of Simplicity: You don't need complex words to describe complex feelings. "Blue on blue" says more than a three-page diary entry ever could.

- Vocal Sincerity over Power: You don't have to be the loudest singer in the room to be the most heard. Vinton's restraint is his greatest strength on this recording.

To really get the full experience, go back and listen to the mono mix if you can find it. The stereo spreads everything out too much, but the mono mix hits you like a wall of sound—or a wall of blue. It’s tighter, punchier, and much more claustrophobic, which is exactly how the song is supposed to feel.

Check out the rest of the Blue on Blue album too. It’s a bizarrely dedicated piece of thematic art for 1963. While most artists were just throwing singles together, Vinton and his producers were trying to build a world. It’s a blue world, sure, but it’s one worth visiting for three minutes at a time.

Next Steps for the Vintage Music Fan

Go find a copy of the original 45rpm record if you're a collector. The B-side was "Those Little Things," which is a decent track, but it pales in comparison to the A-side's perfection. If you're a digital listener, add it to a transition playlist between early 60s pop and the 1964 British Invasion stuff to see just how much the "sound" of the radio changed in just twelve months. Study the bridge of the song—the way the chords shift slightly out of the expected key—and you'll see why Burt Bacharach became a legend. It’s those small, "blue" notes that make the song immortal.