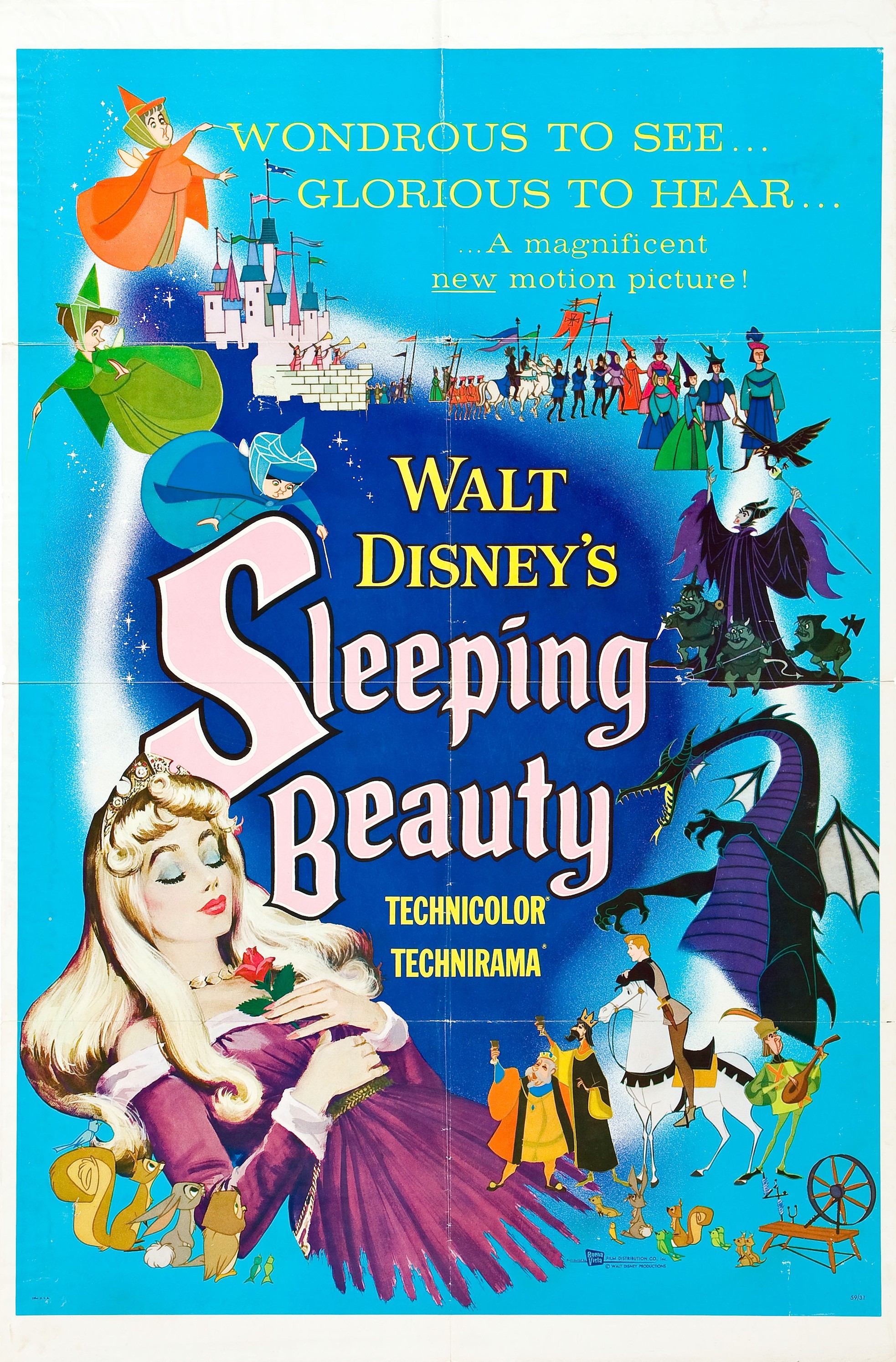

Honestly, it’s hard to wrap your head around the fact that the Sleeping Beauty 1959 film was once considered a massive, studio-threatening failure. Today, we see that distinctive, angular art style and the haunting swell of Tchaikovsky’s score and think "masterpiece." But back in January 1959? Critics weren't exactly lining up to throw roses at Walt’s feet. They thought it was too slow. Too cold. Some even complained it looked more like a moving tapestry than a cartoon.

Walt Disney was betting the farm on this one. Literally.

Production dragged on for nearly a decade. While most animated features of that era took maybe three or four years to wrap, Princess Aurora took six. The budget ballooned to $6 million, which, in 1950s money, was enough to make the board of directors sweat through their suits. If you adjust for inflation, you’re looking at a project that cost more than many modern live-action blockbusters.

The movie is a weird, beautiful paradox. It’s the last of its kind—the final Disney fairy tale produced while Walt was still deeply involved in the day-to-day creative grind, and the last to use hand-inked cels before the studio switched to the cheaper, scratchier Xerox process for 101 Dalmatians.

The Eyvind Earle factor: Why it looks so "different"

If you've ever looked at the Sleeping Beauty 1959 film and felt like you were staring at a medieval cathedral, you can thank Eyvind Earle. Most Disney movies have backgrounds that stay out of the way. They’re soft, watercolor-inspired, meant to let the characters pop.

Earle said no to that.

He was the production designer, and he insisted on a vertical, hyper-detailed style inspired by Renaissance art and Persian miniatures. He wanted every single leaf on every single tree to be visible. This drove the animators absolutely nuts. Legendary guys like Chuck Jones and the "Nine Old Men" found themselves having to simplify their character designs just to fit into Earle’s complex world.

Think about the sheer scale of that labor. A single background painting could take a week to finish. In Cinderella or Snow White, a background might take a day. This wasn't just "making a movie." It was an obsession with a specific visual language that almost nobody in Hollywood understood at the time.

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

A villain who actually stole the show

Let’s be real for a second: Maleficent is the only reason some people even watch this movie.

Voiced by Eleanor Audley—who also gave us the wicked stepmother in Cinderella—Maleficent isn't just a "mean lady." She’s an elemental force. The animators based her movements on a giant bat and gave her those iconic devil horns that have since become a permanent fixture in pop culture.

Unlike the Queen in Snow White, who was driven by vanity, Maleficent is driven by... what, exactly? A missed party invite? That’s what makes her so terrifying. She is petty, powerful, and deeply elegant. When she transforms into the dragon at the end, it isn't just a cool special effect. It was one of the most complex sequences ever animated up to that point. The fire she breathes? It wasn't just "red paint." The effects team used specialized dyes and multi-plane camera work to give it that eerie, neon-green glow that still looks better than half the CGI dragons we see today.

Why the 1959 release was a total disaster

When the Sleeping Beauty 1959 film finally hit theaters, the reception was chilly. It made about $5 million on its initial run. Remember that $6 million budget? Yeah. Disney actually posted its first annual loss in a decade because of this film.

Critics at the New York Times and other major outlets were brutal. They called it "stilted." They felt the romance between Aurora and Phillip was cardboard-thin. And honestly, they sort of had a point about Aurora. She only has about 18 minutes of screen time and 14 lines of dialogue in her own movie.

But what the critics missed was the atmosphere.

Walt wasn't trying to make a fast-paced rom-com. He was trying to create a "living illustration." He wanted people to feel the weight of the forest and the chill of the forbidden mountain. The film was shot in Technirama 70, a wide-screen format that was usually reserved for massive historical epics like Spartacus. To see a "cartoon" in that format was jarring for 1959 audiences. They didn't know how to process it.

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

The music that saved the vibe

You can’t talk about this movie without talking about Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Instead of writing a completely original score, Disney’s music team, led by George Bruns, adapted the music from Tchaikovsky’s 1890 ballet. This was a massive gamble. It meant the animation had to be timed perfectly to the swell of a pre-existing classical masterpiece.

"Once Upon a Dream" is the obvious standout, but listen to the music during the "Battle with the Forces of Evil" at the end. It’s heavy. It’s operatic. It gives the film a sense of "prestige" that Disney hadn't really touched since Fantasia.

Comparing the 1959 version to modern remakes

We’ve seen the live-action Maleficent movies starring Angelina Jolie. They’re fine. They’re successful. But they fundamentally change the DNA of the story.

In the modern versions, Maleficent is a misunderstood hero with a tragic backstory. In the Sleeping Beauty 1959 film, she is just evil. Pure, unadulterated, "Mistress of All Evil" evil. There’s something refreshing about that. There’s no sympathetic flashback to explain why she’s cursing a baby. She’s just a nightmare given form.

Also, the three fairies—Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather—actually drive the plot of the 1959 film. They aren't just comic relief; they are the protagonists. They’re the ones who hide the princess, they’re the ones who arm Prince Phillip with the Shield of Virtue, and they’re the ones who ultimately take down the dragon.

The "woke" debate and historical context

In recent years, people have picked apart the "True Love's Kiss" ending. Some argue it lacks consent because Aurora is asleep. While it's a valid modern lens to look through, in the context of 1950s filmmaking and the original Perrault and Grimm fairy tales, the kiss was a symbolic "breaking of the spell."

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Interestingly, the Sleeping Beauty 1959 film was one of the first times Disney gave the Prince a name and a personality. Before this, the princes were basically nameless dudes who showed up at the end. Phillip has a horse he argues with, a father he bickers with, and he actually goes through a literal hellscape to save the woman he loves.

Technical milestones you probably missed

If you watch the movie on a high-definition 4K screen today, you’ll see things that weren't even visible to audiences in 1959.

- The Multi-plane Camera: This beast of a machine allowed Disney to create a sense of 3D depth. By placing different layers of artwork at varying distances from the lens, the camera could "move through" the forest.

- Live-Action Reference: Almost every frame of the film was shot first with real actors on a soundstage. This is why the dancing in the forest looks so fluid. Helene Stanley, the live-action model for Aurora, also modeled for Cinderella.

- The Color Palette: Notice how the colors change based on the mood. When Aurora is in the forest, the colors are lush greens and berries. When she moves toward the castle and the spinning wheel, the colors shift to oppressive greys and sickly greens.

How to appreciate the film today

If you’re going to rewatch the Sleeping Beauty 1959 film, don't watch it on your phone. This is a movie that demands a big screen. It was designed for the largest theaters of the 1950s, and the details are lost on a small display.

Look at the edges of the screen. Look at the way the rocks are painted in Maleficent’s domain. They look like jagged teeth. Look at the way the fairies’ magic sparkles—it’s not just a generic glitter effect; it was hand-drawn frame by frame to look like falling stars.

The film didn't actually become profitable for Disney until its various re-releases in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. It took decades for the public’s taste to catch up to Walt’s vision. Now, it’s cited by modern directors like Guillermo del Toro as a masterclass in production design.

Actionable steps for fans and collectors

If you want to dive deeper into the history of this specific era of animation, here is how you can actually engage with the legacy of the Sleeping Beauty 1959 film beyond just hitting play on Disney+:

- Visit the Walt Disney Family Museum: Located in San Francisco, they often have rotating exhibits featuring Eyvind Earle’s original concept art. Seeing the scale of the original paintings is a totally different experience than seeing them on a screen.

- Track down the "The Art of Sleeping Beauty" books: There are several out-of-print and specialty coffee table books that break down the background paintings. They are expensive, but for a design nerd, they’re basically the Bible.

- Compare the Aspect Ratios: If you have the Blu-ray, check the settings. Ensure you are watching it in the original 2.55:1 widescreen aspect ratio. If your TV is "zooming" to fit the screen, you are literally cutting off about 30% of the art that took thousands of hours to paint.

- Listen to the Tchaikovsky Ballet: Spend an afternoon listening to the full Sleeping Beauty Op. 66. You’ll start to hear exactly where George Bruns pulled the themes for specific character moments, like the fairies’ theme or the brooding Maleficent motifs.

The Sleeping Beauty 1959 film remains a testament to what happens when an artist (Walt) refuses to compromise, even when it makes zero business sense. It’s a gorgeous, slow, sprawling piece of cinematic history that will never be replicated because, frankly, no studio would ever be "crazy" enough to spend that much time and money on hand-painted leaves again.