Steel. Steam. Thunder. There is something fundamentally primal about a locomotive under full load, but if you're trying to capture that essence on camera or even just visualize the mechanics, the side view of steam train layouts tells the only story that actually matters. Most people look at a train from the front because it’s intimidating. That’s a mistake. The front is just a face; the side is the entire muscular system exposed for the world to see.

I’ve spent years standing in muddy ditches near the Settle-Carlisle line and hunkering down by the tracks in West Virginia just to catch that perfect profile. It’s not just about the "choo-choo" aesthetic. When you look at a steam engine from the side, you aren't just looking at a machine. You are looking at a 200-ton thermodynamic miracle that somehow hasn't exploded.

The geometry of the side view of steam train

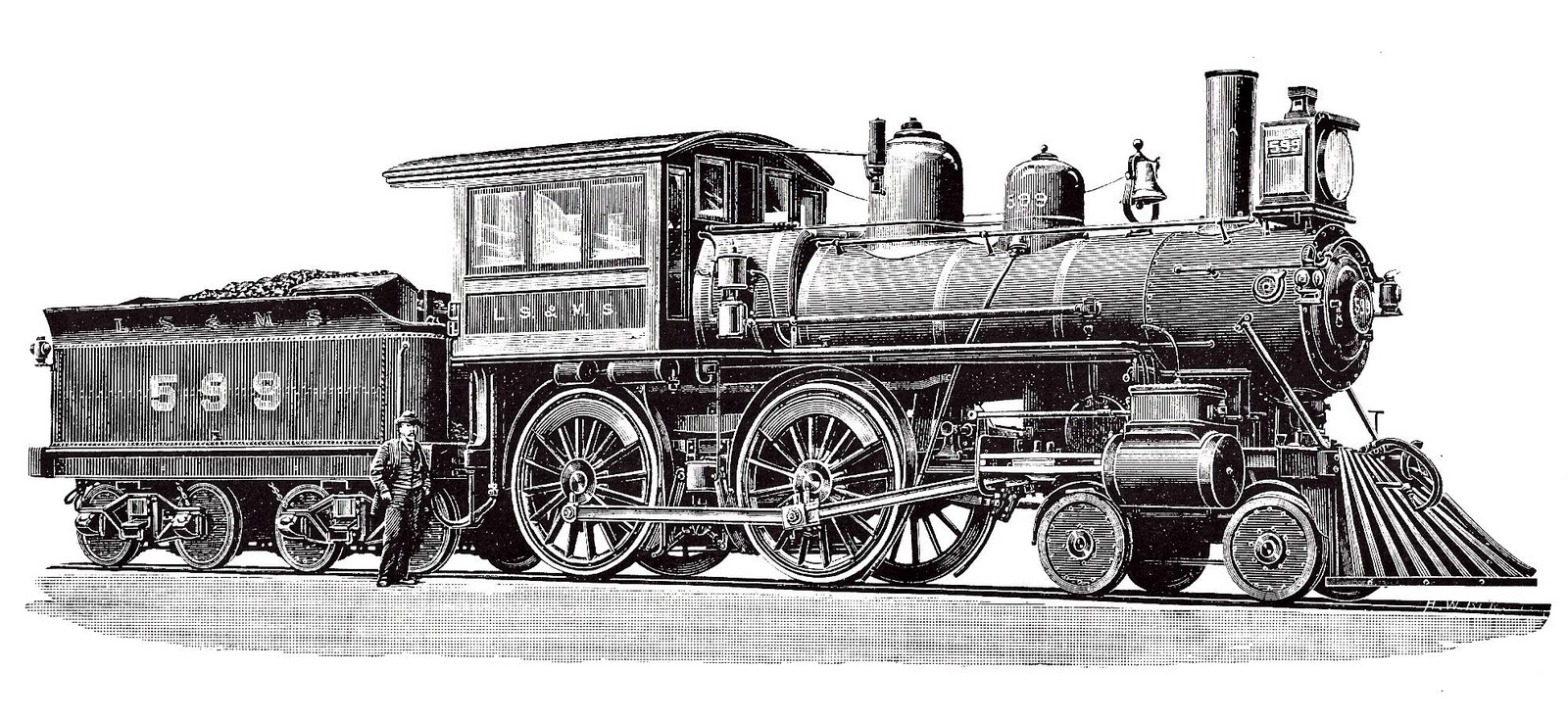

The side profile is where the engineering reveals its secrets. You’ve got the boiler—that massive horizontal cylinder—and underneath it, the driving wheels. These aren't just wheels; they are the heart of the beast. In a classic side view of steam train, you can see the rods moving in a complex, rhythmic dance called the valve gear.

Engineers like Nigel Gresley or André Chapelon didn't just build these things to move; they built them to be efficient. From the side, you can see the "Why." You see the Walschaerts valve gear—that intricate web of steel linkages—shifting back and forth to time the steam injection perfectly. It’s messy. It’s oily. It is also remarkably beautiful in a way a modern electric "toaster" locomotive could never be.

If you’re looking at a 4-6-2 Pacific type engine, that side profile tells you it was built for speed. Those massive driving wheels, sometimes over 6 feet tall, are designed for long strides across open prairies or rolling English countryside. Compare that to a 2-8-8-2 Mallet. From the side, that thing looks like a centipede made of iron. It’s built for raw, mountain-climbing grunt, not a sprint.

Why the rods matter to your eyes

Most casual observers don't realize that the position of the side rods—those heavy bars connecting the wheels—totally changes the "vibe" of a photo or a drawing. Professional railfans wait for the "rods down" position. This is when the main connecting rods are at their lowest point, showing off the full scale of the boiler above them. It creates a sense of grounded power.

✨ Don't miss: Why We Always Blame It on the Moon and What Science Actually Says

If the rods are up, the engine looks a bit spindly, almost like it’s tripping over itself. It’s a tiny detail, but it’s the difference between a snapshot and a portrait.

Lighting the iron: A photographer's nightmare

Getting a good side view of steam train shot is actually a massive pain in the neck. Why? Because trains are usually black. And they are made of reflective steel. And they are surrounded by white steam.

That is a dynamic range nightmare for any camera.

You want "glint." Glint is that sliver of late afternoon sun that catches the top of the boiler and the edges of the driving wheels. Without it, the side of the train just looks like a giant black blob. I’ve seen guys spend three days waiting for the sun to hit a specific curve on the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad just to get the light to pop off the rivets.

- Side-lighting: This is your best friend. It creates shadows in the mechanical bits, giving the image depth.

- Back-lighting: Forget about it unless you want a silhouette.

- Overcast days: Actually great for seeing the oily details without harsh reflections.

The steam itself is another variable. From the side, the "exhaust plume" tells you how hard the engine is working. If the steam is shooting straight up, the train is drifting. If it’s pinned back against the boiler, the engineer is "hammering" it. That trailing white cloud provides a natural frame for the dark metal. It’s nature’s way of giving you a perfect composition.

The "Big Boy" and the scale of the profile

Let’s talk about the Union Pacific 4014, the "Big Boy." If you stand next to it and look at the side, it’s honestly disorienting. It is 132 feet long. That’s longer than a Boeing 737. From the side, you realize the "engine" isn't just one piece; it’s articulated. It hinges.

Seeing that side view of steam train articulation in person explains how something that massive can actually go around a curve without jumping the tracks. It’s two engines sharing one massive boiler. When you see it from the side, you notice the daylight under the boiler, the way the piping snakes along the running boards, and the sheer number of staybolts holding the firebox together.

Basically, the side view is the "truth" of the machine. The front view is just the PR department.

Common misconceptions about what you're seeing

People think the smoke is the power. It's not. The smoke is just waste. The real power is in the "shudder" you see in the side rods when the wheels slip.

Another thing: that big cylinder at the front? That’s not where the fire is. That’s the smokebox. The fire is at the back, right under the cab where the crew sits. When you look at the side view of steam train anatomy, you see the firebox glowing red-hot between the frames. It’s a literal furnace on wheels.

- The Sand Dome: That little hump on top of the boiler. It holds sand to drop on the tracks for grip.

- The Steam Dome: The other hump. That’s where the dry steam is collected before being sent to the cylinders.

- The Baker Valve Gear: A specific type of linkage that doesn't use links. (Confusing, I know, but it’s a favorite for American heavy freight).

Honestly, the more you look, the more you realize these machines are almost biological. They breathe. They leak. They groan.

Technical nuances of the side profile

The "side view" isn't just a 90-degree angle. The best views are often at a "three-quarters" perspective, but the pure profile is what you find in engineering blueprints. These blueprints are a lost art form. In the 1920s, a side-elevation drawing of a Pennsylvania Railroad K4 was a masterpiece of draftsmanship.

Every bolt was accounted for. Every lubrication line was traced.

If you are trying to model these or draw them, you have to get the "stance" right. A steam locomotive sits on its springs in a very specific way. If you draw the boiler too high, it looks top-heavy. Too low, and it looks like the suspension is blown. The gap between the top of the wheels and the bottom of the running board is the "soul" of the engine's silhouette.

How to actually appreciate the side view of steam train in the wild

If you want to see this for yourself, don't just go to a museum where the engines are cold and dead. Go to a heritage line. Go to the Strasburg Rail Road in Pennsylvania or the Bluebell Railway in the UK.

Position yourself about 50 feet back from the track, perpendicular to a slight uphill grade. This is crucial. You want the engine to be working.

As it passes, watch the "crosshead"—the part that slides back and forth to turn the piston's linear motion into the wheels' circular motion. It’s the most violent, high-speed friction you’ll ever see. Then, look at the "counterweights." Those are the crescent-shaped chunks of metal on the wheels. They are there to balance the weight of the rods so the engine doesn't literally bounce off the tracks at high speed.

It's a delicate balance of thousands of pounds of flailing steel.

Actionable steps for your next sighting:

- Check the "Quartering": Look at the wheels on the left side versus the right. They are always 90 degrees out of phase. This ensures the engine never gets "stuck" on a dead center point. If you see it from the side and the rod is at the very front, the other side is either at the top or bottom.

- Listen to the "Blast": The sound comes from the exhaust steam being shot up the chimney to create a vacuum for the fire. From the side, you can perfectly time the "chuff" with the movement of the rods. Four chuffs per revolution for a standard two-cylinder engine.

- Watch the Piston Packing: Look for little wisps of steam escaping near the front cylinders. That’s where the power lives. Too much steam escaping means the engine needs a trip to the workshop.

- Note the Livery: Some railroads used "lining"—thin painted stripes—to emphasize the horizontal lines of the side view of steam train. It makes the engine look longer and faster. The LNER "Apple Green" or the Norfolk & Western "Tuscan Red" are classic examples where the side view was a canvas for branding.

Steam is fleeting. We’re lucky we still have these things running at all. The next time you see one, step back from the crowd at the front of the platform. Walk down toward the middle of the train. Look at the linkages, the scale of the boiler, and the way the light hits the grime on the wheels. That's where the real story is.

Go find a local excursion or a "photo charter." These are events specifically designed for people who want to see the engine in its best light. They’ll often do "run-pasts" where the train backs up and then comes forward at speed just so you can catch that perfect profile. It’s worth the ticket price just to see the valve gear in motion at 40 miles per hour. No textbook or YouTube video can replace the feeling of that much vibrating metal passing three feet from your chest.

Study the wheel arrangements—the Whyte notation. When you can look at a side profile and instantly say "That’s a 2-8-4 Berkshire," you’ve unlocked a whole new level of appreciation for the industrial age. The machine stops being a "train" and starts being a specific, historical individual with its own quirks and mechanical "personality."