Stanley Kubrick was a perfectionist. Everyone knows that. But when you actually sit down and look at the shining movie scenes through a modern lens, you realize it wasn't just about being a difficult boss. It was about visual psychological warfare. The movie doesn't just tell a story about a guy losing his mind in a hotel; it uses the very architecture of the screen to make you feel like you’re losing yours, too. Honestly, it’s kinda terrifying how well it still works.

Think about the first time we see the Grady twins. They aren't jumping out from behind a corner. They’re just... there. Standing at the end of a long, floral-carpeted hallway. It’s the stillness that kills you.

The Impossible Geography of the Overlook

One thing people rarely notice on a first watch—but it’s why the movie feels so "off"—is that the Overlook Hotel literally cannot exist. Kubrick and his production designer, Roy Walker, intentionally built sets that are physically impossible. In one of the most famous of the shining movie scenes, Jack Torrance is sitting in Ullman’s office. There’s a window behind Ullman showing bright daylight. But if you look at the floor plan of the hotel we just walked through to get there, that office should be in the middle of the building. It’s surrounded by other rooms. There shouldn't be a window there.

It’s a "ghost window."

You don't consciously see it, but your brain registers the spatial inconsistency. It creates this low-level hum of anxiety. This isn't just a filming mistake; Kubrick was notorious for hundreds of takes to get things exactly right. He wanted the audience to feel geographically lost. When Danny is riding his Big Wheel through the corridors, the sound transitions from the hardwood to the carpet—vroom-thud-vroom-thud—it’s hypnotic. But if you track his turns, he’s looping through spaces that don't connect. You’ve probably felt that weird vertigo while watching it. That’s the "impossible architecture" at work.

The Blood Elevator and the Art of the Slow Motion Nightmare

Let’s talk about the elevator. You know the one. Thousands of gallons of stage blood (actually mostly water and food coloring, which is why it looks so bright and fluid) bursting through the doors.

It’s one of the most iconic of the shining movie scenes, yet it almost didn't make it into the trailer. The MPAA had strict rules about showing blood in trailers. Kubrick, being the master of technicalities, convinced them it wasn't blood—it was just "rusty water." They bought it.

🔗 Read more: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

Watching that scene in slow motion is a masterclass in tension. It took nearly a year to prep that one shot. They only had one chance to get it right because cleaning the set would have taken weeks. When the doors finally buckle under the weight, the sheer volume of liquid is staggering. It’s not just a jump scare. It’s a visual representation of the hotel’s "shining"—a psychic bleed that can no longer be contained by the walls of the building. It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s beautiful in a grotesque sort of way.

Jack Nicholson, The Axe, and 60 Doors

"Heeeere’s Johnny!"

Jack Nicholson improvised that line. Kubrick, who lived in England at the time, actually didn't even know what the reference was. He almost cut it. Can you imagine the movie without it? It’s probably the most quoted moment in horror history.

But the real story behind this sequence is the physical exhaustion. To film the bathroom door scene, the production went through roughly 60 doors. Nicholson had actually worked as a volunteer fire marshal, so he was way too good at swinging an axe. He was shredding the prop doors too quickly. They had to switch to heavier, solid wood doors just so the wood would splinter realistically and give Shelley Duvall more time to react.

The terror on Duvall’s face? That’s not just acting. Kubrick notoriously pushed her to the brink of a breakdown. He wanted her "in a state of hysteria" for months. While it produced a legendary performance, the ethics of his directing style are still debated today. You can see the genuine exhaustion in her eyes during the "Staircase Scene" where she’s swinging the baseball bat. That scene holds a world record for the most takes of a scene with spoken dialogue—127 times. By the end, her hands were raw. She was dehydrated from crying. It’s a brutal watch because you’re seeing real human suffering on screen.

The Steadicam Revolution

We have to mention Garrett Brown. He invented the Steadicam, and the shining movie scenes were its first real trial by fire. Before this, cameras were either on heavy dollies or handheld and shaky.

💡 You might also like: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Kubrick wanted something different. He wanted the camera to float.

The low-angle shots following Danny’s tricycle were achieved by Brown sitting on a "wheelchair" rig that Kubrick’s crew modified. It allowed the camera to glide just inches above the floor. This perspective is vital. It puts us at the height of a child. It makes the hotel look towering and predatory. When the camera follows Jack into the Gold Room or Danny into the snowy maze, it feels like a predatory spirit following them. It’s smooth, detached, and relentless. It doesn't flinch.

Room 237 vs. Room 217

In Stephen King’s book, it was Room 217. In the movie, it’s 237.

Why the change? The Timberline Lodge, which was used for the exterior shots of the Overlook, actually had a Room 217. The management was terrified that guests would be too scared to stay there after seeing the movie. So, they asked Kubrick to use a non-existent room number. They figured 237 was safe.

Ironically, Room 237 is now the most requested room number in hotel history, even in hotels that have nothing to do with the movie.

The scene inside that room—the transition from the beautiful woman in the bathtub to the decaying hag—is a literalization of the "bait and switch" of the Overlook. The hotel shows you what you want to see (liquor, companionship, importance) before revealing the rot underneath. Jack’s face when he realizes what he’s holding is a masterclass in subtle horror. The way his smile just... curdles.

📖 Related: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

The Ending That Still Divides Fans

The hedge maze. The chase. The frozen Jack.

The final shot of the film is a slow zoom into a photograph from 1921. There’s Jack, smiling in the middle of a crowd. "Say, it's been a long time, hasn't it?"

What does it mean? Is Jack a reincarnation? Did the hotel "absorb" his soul? Kubrick never gave a straight answer. He preferred the ambiguity. In the original script, there was a hospital scene after the maze where Ullman visits Wendy and Danny, telling them they found nothing unusual at the hotel. He then hands Danny the same yellow ball that rolled into the hallway earlier. It was a final "gotcha." Kubrick cut it at the last second because he felt the photo was a stronger, more haunting note to end on. He was right.

How to Analyze These Scenes Like a Pro

If you're looking to really "get" the depth of these sequences, stop watching the characters. Start watching the background.

- Look for the "Cross" shadows: Kubrick uses lighting to create subtle religious and sacrificial imagery.

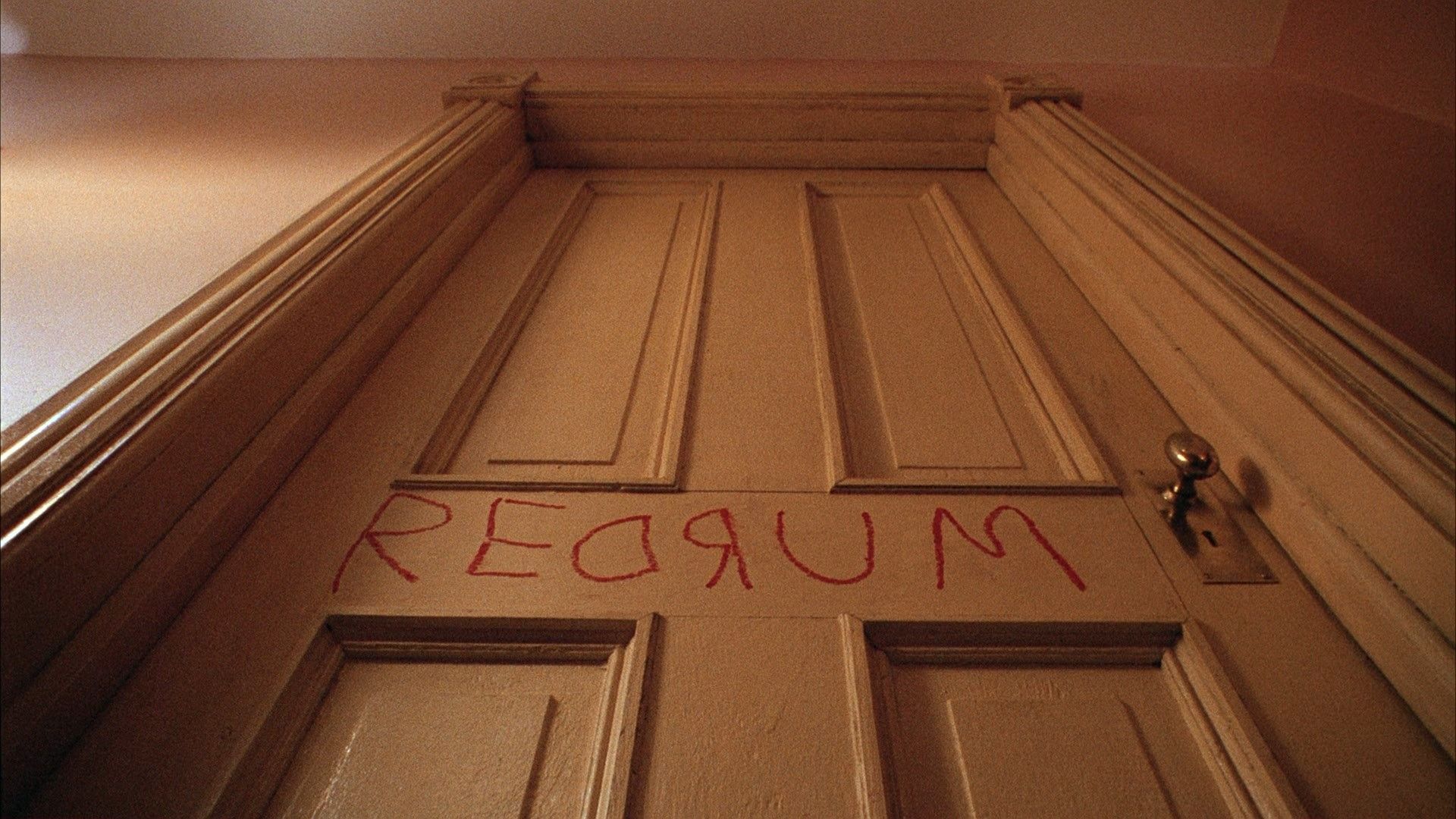

- Track the colors: Notice how the "Redrum" red starts appearing in the decor long before the reveal.

- The Mirror Rule: Almost every time Jack talks to a ghost (Grady, Lloyd the bartender), there is a mirror involved. It suggests he’s really just talking to himself—or a reflection of his own inner darkness.

The next time you sit down to watch, pay attention to the silence. Most modern horror movies rely on loud bangs and "stingers" to scare you. The Overlook just sits there. It waits. It lets the carpet patterns and the impossible hallways do the heavy lifting. That's why it's still the gold standard for psychological cinema.