It is basically a giant metal thermos filled with pipes. That sounds a bit reductive, but if you’ve ever stood next to a shell and tube heat exchanger in a refinery or a power plant, you know they are anything but simple. They are the workhorses of the thermal world. While newer, sleeker plate heat exchangers get a lot of love for being compact, the shell and tube design remains the undisputed king when things get hot, high-pressure, or just plain dirty.

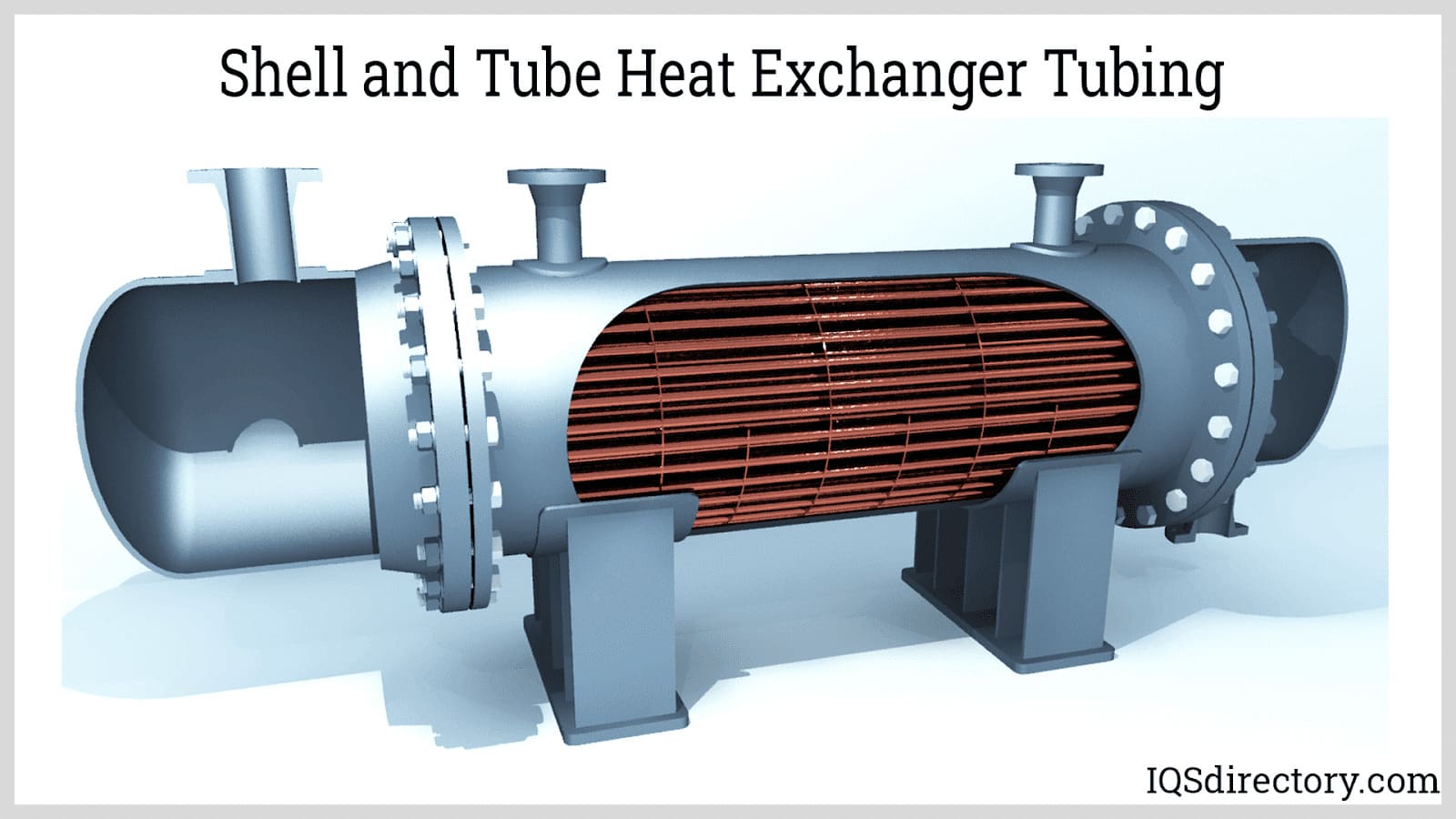

Think about the sheer scale. You have one fluid flowing through a bundle of tubes, and another fluid sloshing around outside them in a massive outer shell. They never touch. Heat moves through the tube walls. It’s a concept that dates back over a century, yet we still haven't found a better way to handle the brutal conditions of a nuclear reactor or a chemical processing line.

✨ Don't miss: Spectrum in Clayton North Carolina: What You’ll Actually Pay and How to Get Better Speeds

The "Skeleton" of the System: Anatomy and Why It Matters

Most people look at the exterior and see a big cylinder. Boring, right? The magic is actually in the internal geometry. You have the tube bundle, which is exactly what it sounds like—a collection of tubes that can number in the thousands. These are held in place by tube sheets, which are thick, precision-drilled plates. If those sheets aren't sealed perfectly, you get cross-contamination. In a food processing plant, that’s a disaster. In a refinery, it’s a potential explosion.

Then there are the baffles. These are internal "fences" that force the shell-side fluid to zigzag back and forth. Without them, the fluid would just take the path of least resistance and flow straight through, which ruins the heat transfer efficiency. By forcing the fluid to cross the tubes perpendicularly, you create turbulence. Turbulence is your best friend in thermodynamics. It keeps the "boundary layer" thin, letting heat escape or enter the tubes much faster.

Fixed vs. Floating: The Great Thermal Expansion Debate

Metal grows when it gets hot. You know this from bridge joints clicking in the summer. In a shell and tube heat exchanger, if the tubes get 400 degrees hotter than the shell, they will expand. If both ends are welded shut (a "fixed tube sheet" design), something is going to snap.

That is why engineers use a floating head. One end of the tube bundle is literally not attached to the outer shell. It "floats," moving back and forth as temperatures fluctuate. It’s more expensive. It’s a pain to maintain because of the extra gaskets. But it saves the entire unit from tearing itself apart under thermal stress. Honestly, if you're dealing with a temperature delta of more than 100°F between the two fluids, you should probably be looking at a floating head or a U-tube design.

Why We Can't Just Use Plate Exchangers for Everything

Plate heat exchangers are efficient. Everyone says so. They have a higher "U-value" (heat transfer coefficient). But they are fragile. Try running high-pressure steam through a plate exchanger and watch the gaskets fail instantly.

The shell and tube heat exchanger is the tank of the industry. It can handle pressures exceeding 1,000 psi without breaking a sweat. It also handles "fouling"—the buildup of gunk, minerals, or biological growth—much better. If your tubes get clogged with river water sediment, you can just pop the heads off and run a mechanical brush through them. You can't really do that with the tight channels of a plate-frame unit.

📖 Related: Apple Store 1 Infinite Loop: Why It Is Still Worth the Trip

Real-World Nuance: The TEMA Standards

If you're buying or designing one of these, you aren't just winging it. You’re following TEMA (Tubular Exchanger Manufacturers Association) standards. These are the "bible" for this technology. They categorize exchangers into three main classes:

- Class R: For the soul-crushing conditions of petroleum refining. These are built to be indestructible.

- Class C: For general commercial applications. Think HVAC or light manufacturing.

- Class B: For chemical processes where corrosion is a bigger worry than sheer pressure.

You’ll often see codes like "BEM" or "AES." The first letter describes the front head, the second is the shell type, and the third is the rear head. An "AEL" unit, for example, has a removable cover and a fixed tube sheet. It’s a shorthand language that lets engineers communicate without drawing 500 pages of blueprints every time they talk shop.

The Problem with Vibration

Here is something most textbooks gloss over: Flow-Induced Vibration (FIV). When you pump fluid at high speeds across thousands of thin tubes, they start to hum. If that hum hits the natural frequency of the metal, the tubes will vibrate until they hit each other or the baffles. This leads to "tube thinning" and eventually a leak. It sounds like a scream coming from inside the pipes.

To fix this, we use things like deriving the baffle spacing or adding "no-tubes-in-window" designs. It’s a delicate balance. You want high velocity for heat transfer, but not so much that the machine shakes itself to death.

Practical Insights for Maintenance and Performance

You can't just install a shell and tube heat exchanger and forget it exists for twenty years. Maintenance is where the real money is lost or saved.

- Monitor the Pressure Drop: If the "delta P" starts climbing on your gauges, you have a fouling problem. Don't wait for the heat transfer to drop. By the time your outlet temperature is off, the scale inside is already rock-hard.

- Sacrificial Anodes: If you’re using seawater or corrosive fluids, you need zinc anodes. They corrode so your expensive alloy tubes don't. Replace them every year. It’s cheap insurance.

- Eddy Current Testing: Once a year, or during a turnaround, run an eddy current probe through the tubes. It can "see" through the metal to find pits or cracks before they turn into a catastrophic failure.

The industry is moving toward "smart" monitoring. We’re seeing more ultrasonic sensors clamped to the shell to detect early signs of scale buildup. It’s pretty cool stuff, though most old-school plant managers still prefer the "tap it with a wrench and listen" method.

Final Strategic Takeaways

Choosing the right configuration depends entirely on your specific "pain point." If space is your biggest constraint but your pressure is low, go plate. But if you are dealing with extreme temperatures, high pressure, or dirty fluids, the shell and tube is your only real choice.

👉 See also: CERN: What Does It Stand For and Why Does the Name Sound So Different?

When specifying a unit, always ask for the "fouling factor" used in the calculations. Some manufacturers lowball this to make their unit look smaller and cheaper. If your fluid is messy, you want a generous fouling factor so the exchanger still works in six months when it's half-covered in slime.

- Verify your metallurgy: Don't use carbon steel if there's even a hint of H2S or high chlorides. Go duplex or titanium.

- Check the bypass: Ensure you have a bypass valve installed. If you need to clean the unit, you don't want to shut down the entire plant.

- Analyze the fluid velocity: Keep it high enough to prevent settling but low enough to avoid erosion. Usually, 3-8 feet per second for liquids is the sweet spot.

Stop thinking of these as static pieces of hardware. They are dynamic systems. Treat them with a bit of respect, keep the tubes clean, and a well-built shell and tube unit will probably outlive most of the people working in the plant.