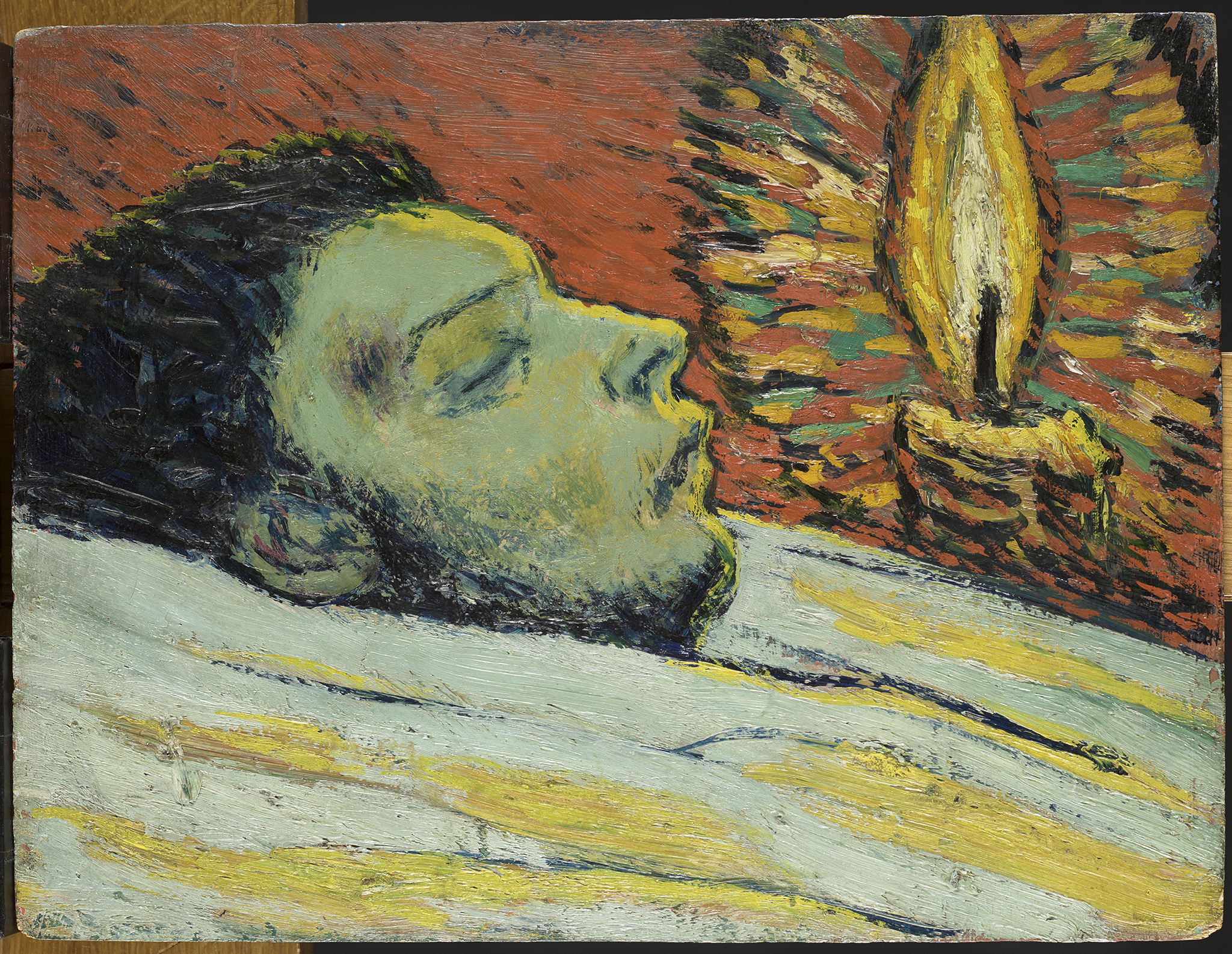

He was broke. Honestly, in 1904, Pablo Picasso was basically a starving artist in the most literal, cliché sense of the word, living in a dilapidated Montmartre building known as the Bateau-Lavoir. If you’ve ever seen his Blue Period works, you know the vibe: cold, miserable, and drenched in a depressing monochromatic indigo that feels like a heavy blanket. But then, things shifted. The rose period of picasso didn't just happen because he bought some new tubes of paint. It was a psychological pivot. He moved away from the imagery of beggars and the blind, trading that deep sorrow for something warmer—though, if you look closely, it wasn't exactly "happy" in the traditional sense.

It’s easy to look at a painting like Family of Saltimbanques and think, "Oh, look, circus people." But there’s a weirdness there. A stillness.

The Transition from Blue to Pink

The shift started around 1904 and lasted until roughly 1906. You’ve probably heard people say it was all because he met Fernande Olivier. While his relationship with Fernande—a French artist and model—definitely cheered him up, the rose period of picasso was also about him finding a niche in the Parisian art market. He was starting to sell. When you aren't worried about where your next piece of bread is coming from, your art tends to lose that "starving in a garret" edge.

The color palette changed to shades of pink, shell-flesh, coral, and ochre.

It was warmer. It felt more alive.

Yet, the subjects remained outsiders. Instead of the destitute, he painted saltimbanques—itinerant circus performers. These people were the 1905 version of gig workers. They traveled, they performed, and they lived on the fringes of society. Picasso identified with them. He saw the artist as a kind of performer, someone who entertains but remains fundamentally separate from the audience. This wasn't a period of joyous celebration; it was a period of "equipoise," as some critics put it. It was a delicate balance between the tragedy of his earlier work and the structural experimentation that would eventually lead him to Cubism.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Why Harlequins Became a Permanent Fixation

If you look at his work from 1905, you'll see a lot of Harlequins. Specifically, the checkered suit. Picasso used the Harlequin as a personal avatar. It’s a bit meta when you think about it. The Harlequin is a trickster, a character from the commedia dell'arte who is clever but often lonely.

By painting himself or his friends as these performers, he was making a statement about the role of the creator. He wasn't just "painting a guy in a suit." He was exploring the idea of the mask. In At the Lapin Agile, he depicts himself as a Harlequin sitting at a bar, looking completely detached from the woman next to him. It's moody. It's stylish. It also shows that the rose period of picasso wasn't just a "happy phase"—it was a sophisticated exploration of social alienation.

The Influence of the Steins and the Money Trail

Money matters in art history. It just does. In 1905, Picasso caught the eye of Leo and Gertrude Stein. This was huge. They were the ultimate tastemakers in Paris at the time. Gertrude Stein eventually bought Young Girl with a Flower Basket, a painting that really encapsulates the era: a combination of youthful innocence and a certain hard, street-smart reality.

The Steins didn't just give him money; they gave him a social circle. This exposure helped push the rose period of picasso into the collections of serious people. Suddenly, he wasn't just the "sad blue guy." He was a rising star.

- He started experimenting with more classical forms.

- The influence of Greek and Roman statuary began to creep in.

- The figures became more solid, less ghostly than the Blue Period figures.

- He spent time in Gosol, Spain, in 1906, which completely changed his approach to the human face.

That trip to Gosol is often cited by experts like Pierre Daix as the "true" turning point. The air was different. The light was different. He started simplifying features. If you look at the portraits from late 1906, you can see the eyes becoming more almond-shaped, the faces becoming more like masks. This was the bridge. The rose period of picasso was effectively the runway for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Misconceptions: It Wasn't Just About Being "In Love"

A lot of people want to simplify this to: "He got a girlfriend, so he used pink paint." That’s a bit insulting to his intelligence. Picasso was an obsessive sponge. He was looking at Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. He was looking at Puvis de Chavannes. He was trying to figure out how to represent the human body without just "copying" it.

The "Rose" label itself is a bit of a later invention by art historians to make his career easier to categorize. At the time, he was just working. He was moving through a fascination with the circus and moving toward a fascination with "primitivism" and African art.

Also, the colors aren't always rose. There’s a lot of terracotta. There’s a lot of grey. The Boy Leading a Horse (1906) is a great example. It’s massive. It’s monumental. But the colors are muted. It has more in common with a dusty Roman fresco than a greeting card. This period showed he could handle scale. He was moving away from small, intimate canvases to works that demanded space on a wall.

The Technical Evolution

One thing people overlook is his line work. In the Blue Period, the lines were often sharp, jagged, and harsh. In the rose period of picasso, the lines softened. They became more fluid. He was drawing with a certain grace that he’d previously suppressed.

He was also obsessed with the "weight" of things. You can see it in the way his circus performers stand. They aren't floating; they are grounded. Even the thin, wiry acrobats have a sense of gravity. This focus on volume was a precursor to his later obsession with three-dimensional form in two-dimensional space. Basically, he was learning how to make things look heavy before he decided to break them into cubes.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

How to Spot a Rose Period Masterpiece

If you’re in a museum—say, the Met in New York or the Musée Picasso in Paris—and you want to identify a work from this era without reading the plaque, look for these specific "tells":

- The Subject Matter: If there’s a circus tent, a drum, a horse, or a guy in a checkered suit, you’re likely in the Rose territory.

- The Eyes: They are often large but somewhat blank. There’s a "staring into the distance" quality that feels very specific to 1905.

- The Palette: Look for "dirty" pinks. It’s rarely a bubblegum pink. It’s usually mixed with white or brown, giving it a dusty, antique feel.

- The Composition: The figures are often grouped together but don't seem to be interacting. It’s like a photo of people who are together but all on their phones—except, you know, it’s 1905 and they’re just lost in thought.

What This Means for You Today

Understanding the rose period of picasso isn't just for art history majors. It’s a lesson in "the pivot." Picasso was stuck in a rut. He was depressed. He was known for one specific, gloomy style. He could have stayed there forever. But he allowed his environment, his relationships, and his new interests to pull him into a different headspace.

He didn't jump straight into Cubism. He needed this middle ground. He needed a space to experiment with warmth and volume before he went full-on avant-garde.

If you want to dive deeper into this, don't just look at digital scans. Digital screens ruin the texture. If you can, find a high-quality art book—specifically something that focuses on his early years in Paris. Look at the sketches. Picasso was a relentless draughtsman. His sketches for Family of Saltimbanques show how many times he repositioned the figures just to get that feeling of "together yet alone" exactly right.

Actionable Insights for Art Enthusiasts:

- Visit the National Gallery of Art in D.C.: They house Family of Saltimbanques. Stand in front of it for at least ten minutes. Notice how the ground looks like a desert. Why? There’s no right answer, but thinking about it changes how you see the work.

- Compare side-by-side: Find a print of The Old Guitarist (Blue) and Boy with a Pipe (Rose). Look at the shoulders. In the Blue Period, the shoulders are hunched and defeated. In the Rose Period, they start to square up.

- Read Fernande Olivier’s memoirs: If you want the real "boots on the ground" story of what his life was like during the rose period of picasso, her book Picasso and His Friends is a must-read. She doesn't hold back on the grit of their daily lives.

- Trace the Harlequin: Follow the Harlequin motif through his later work. You'll see how this character he developed in 1905 stayed with him for decades, constantly evolving as his style changed.

Picasso's Rose Period was the "calm before the storm." It was a moment of beauty and classicism before he decided to tear the visual world apart and put it back together in a way no one had ever seen before. It reminds us that growth is iterative. You don't go from zero to genius overnight; you go from blue to rose, and then to everything else.