You think you know the Rockies. You’ve seen the postcards of jagged peaks in Colorado or maybe the turquoise waters of Banff. But if you actually sit down and look at a rocky mountains map north america style, the scale is honestly terrifying. We are talking about a literal spine of a continent. It stretches more than 3,000 miles. That’s roughly the distance from New York City to London, but instead of ocean, it’s all rock, ice, and thin air.

It’s huge.

Most people treat the Rockies like a single neighborhood. In reality, it’s a collection of at least 100 separate mountain ranges. If you’re looking at a map, you can’t just point to one spot. You have to trace a line from the Liard River in British Columbia all the way down to the Rio Grande in New Mexico. And even then, you’re probably missing the nuances that make this geographical feature the most complex part of the Western Hemisphere.

Understanding the True Borders on a Rocky Mountains Map of North America

Geography is messy. Geologists like Marli Miller have pointed out for years that the boundaries of the Rockies aren't as clean as the lines on a gas station map. To the east, they basically just stop. They hit the Great Plains and quit. If you’re driving west through Kansas or Nebraska, the horizon is flat until, suddenly, it isn't. The "Front Range" rises up like a wall.

To the west, though? It’s a disaster of definitions.

The Rockies are bordered by the Interior Plateau and the Columbia Plateau. But then you’ve got the Basin and Range province. Is the Wasatch Range in Utah part of the Rockies? Most experts say yes. But what about the Sierra Nevada? Absolutely not. Even though they look similar on a satellite image, the Sierras are a different beast entirely, formed by different tectonic tantrums.

When you look at a rocky mountains map north america provides, you’ll notice four distinct sections:

- The Canadian Rockies: These are the ones that look like shark teeth. They were carved heavily by glaciers, creating those U-shaped valleys that make places like Jasper look so dramatic. They are mostly limestone and shale.

- The Northern Rockies: Think Montana and Idaho. This is where the Bitterroot and the Salmon River Mountains live. It’s rugged, remote, and where you’re most likely to get lost for a week without seeing another human.

- The Middle Rockies: This includes the high-altitude plateaus of Wyoming and the famous Tetons. The Tetons are weird because they don't have "foothills." They just explode out of the ground.

- The Southern Rockies: Colorado and New Mexico. This is where the air gets really thin. Colorado alone has 58 "Fourteeners"—peaks over 14,000 feet.

The Geologic "Mistake" That Created the Range

Usually, when mountains form, it’s because two plates smash together right at the coast. Think of the Andes in South America. But the Rockies are weird. They are hundreds of miles inland. For a long time, scientists were kinda stumped about why they popped up so far from the Pacific plate boundary.

💡 You might also like: Redondo Beach California Directions: How to Actually Get There Without Losing Your Mind

The answer is something called the Laramide Orogeny.

Basically, about 80 million years ago, a tectonic plate (the Farallon Plate) started sliding under the North American Plate. But instead of diving deep into the earth at a steep angle, it slid horizontally. Imagine sliding a rug under a door. Eventually, that "rug" caused the crust way inland to bunch up and break. That’s why the Rockies exist where they do. It was a shallow-angle subduction that pushed the mountains up in the middle of the continent.

It wasn't a fast process. We are talking millions of years of slow-motion crunching. And it wasn't just one event. There were multiple pulses of mountain building. If you look at the rocks in the Grand Canyon (not the Rockies, but nearby) versus the rocks in Rocky Mountain National Park, you’re looking at vastly different timelines. The core of the Rockies is often ancient Precambrian metamorphic rock—some of the oldest stuff on the planet, pushed up through younger layers of sediment.

Why the Continental Divide Changes Everything

If you’re staring at a rocky mountains map north america, you’ll see a dashed line snaking through the peaks. That’s the Continental Divide. It’s the literal roof of the continent.

If you pour a glass of water on the west side of that line, it’s eventually going to hit the Pacific Ocean. Pour it a few inches to the east? It’s headed for the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico. This isn't just a fun trivia fact; it dictates the entire ecology of the United States and Canada.

The mountains act as a giant "rain shadow." Moist air comes off the Pacific, hits the Rockies, and is forced upward. As it rises, it cools and drops its moisture as snow or rain. By the time the air clears the peaks and heads toward the Great Plains, it’s dry. That’s why Denver is a semi-arid high desert while the mountains just 40 miles west get 300 inches of snow a year.

The Ecosystems You’ll Find

The Rockies aren't just "mountainous." They are a vertical staircase of different worlds.

📖 Related: Red Hook Hudson Valley: Why People Are Actually Moving Here (And What They Miss)

- Montane Zone: At the bottom, you’ve got ponderosa pines and Douglas firs. It’s dry and smells like vanilla if you sniff the bark.

- Subalpine Zone: Higher up, the trees get skinnier. Subalpine fir and Engelmann spruce dominate here. This is where the snow stays until July.

- Alpine Tundra: Above the "treeline," usually around 11,000 feet in the south and lower as you go north. Nothing grows here except moss, lichens, and tiny wildflowers that have to survive hurricane-force winds. It looks like the surface of Mars or maybe the Arctic.

Living on the Map: Human History and Modern Issues

People have been navigating this map for at least 10,000 years. The Paleo-Indians used the mountain passes to hunt mammoth and bison. Later, tribes like the Ute, Shoshone, and Blackfeet knew the geography better than any modern GPS could ever hope to. They knew where the "low" passes were—the places where you wouldn't die of exhaustion trying to cross.

Then the Europeans showed up. Lewis and Clark famously realized their "water route" to the Pacific was a myth when they saw the Bitterroot Range. They expected a small hill; they found a wall of granite.

Today, the map is changing.

Climate change is hitting the Rockies harder than many other places. The "snowpack"—the massive amount of frozen water that sits on the peaks—is melting earlier every year. This is a huge deal because the Rockies are the "water towers" for the West. The Colorado River, which supports 40 million people and massive amounts of agriculture in California and Arizona, starts as a tiny trickle of snowmelt in the Colorado Rockies. If that snow goes away, the map of the American West as we know it basically collapses.

Also, we have to talk about the pine beetles. Because winters aren't getting cold enough to kill them off, these beetles have devastated millions of acres of forest. When you look at the mountains now, you see massive patches of "red" or "grey" trees. Those are dead forests. They are essentially giant matchsticks waiting for a lightning strike.

The Most Iconic Spots on the Rocky Mountains Map

If you’re planning a trip or just studying the range, you can't miss these specific anchors. They define the character of the different sections.

Glacier National Park (Montana)

The "Crown of the Continent." This is where the ecosystem is most intact. You still have grizzlies, wolves, and wolverines. The mountains here are made of sedimentary rock that has been pushed over younger rock, a weird geological flip-flop called the Lewis Overthrust.

👉 See also: Physical Features of the Middle East Map: Why They Define Everything

The Wind River Range (Wyoming)

This is the backpacker’s holy grail. It’s not as famous as the Tetons, but it’s more rugged. It has the largest glaciers in the American Rockies. If you want to see what the world looked like 10,000 years ago, go here.

The San Juans (Colorado)

These are the "Switzerland of America." They are volcanic in origin, which makes them look different from the rest of the Rockies. They are steep, crumbly, and incredibly green in the summer.

Banff and Jasper (Alberta)

This is the northern extreme. The mountains here feel "taller" because the valley floors are lower. The icefields—like the Columbia Icefield—are remnants of the last ice age and are some of the few places you can actually walk on a glacier.

Practical Insights for Navigating the Rockies

If you’re actually going to use a rocky mountains map north america to travel, forget everything you know about distance.

In the plains, 60 miles takes an hour. In the Rockies, 60 miles can take three hours. You have to account for switchbacks, 10% grades that make your brakes smoke, and the occasional mountain goat jam.

Altitude is a real thing. If you’re coming from sea level to somewhere like Leadville, Colorado (10,152 feet), you are going to feel like garbage for two days. Your blood literally can't carry enough oxygen. Drink twice as much water as you think you need. Seriously. Alcohol also hits about twice as hard at 9,000 feet. You've been warned.

Weather is unpredictable. I’ve seen it snow in July in the Bighorns. If you are hiking, you need to be off the high ridges by noon. Lightning storms in the Rockies are terrifying and move faster than you can run.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Check the SNOTEL data: If you're interested in the current state of the mountains, look up SNOTEL (Snow Telemetry) sites. It gives you real-time data on how much water is actually sitting on the mountains.

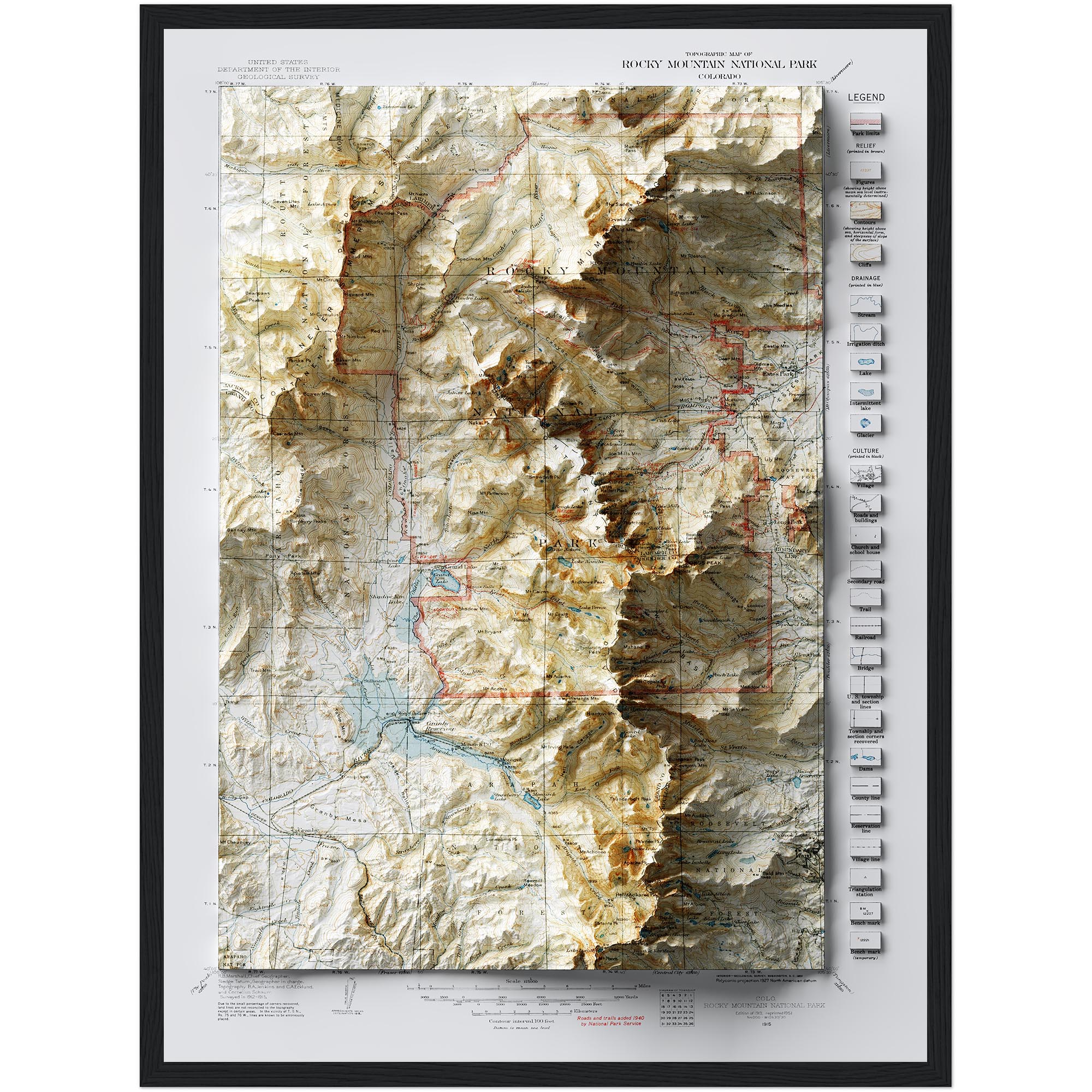

- Use Topographic Maps: Standard road maps are useless for the Rockies. Use tools like Gaia GPS or OnX to see the actual "relief" of the land.

- Study the "Passes": If you're driving, look at the elevation of the passes (like Loveland Pass or Rogers Pass). These are the choke points of North American transit and the first places to close when a storm hits.

- Look into the "Yellowstone Hotspot": It’s technically part of the Rocky Mountain system, but it’s a volcanic anomaly that has its own unique geological rules.

The Rockies aren't just a background for your photos. They are a living, breathing, and occasionally crumbling piece of the earth’s crust that dictates how we live, where our water comes from, and how we move across the continent. Respect the map, but respect the mountains more. They were here long before us, and they’ll be here long after we’re gone.