The ground feels solid. You’re standing on it right now, probably thinking it’s the most stable thing in your life. It isn’t. We are basically riding on giant, jagged rafts of rock that are constantly crashing into, sliding under, or ripping away from one another. This is the messy reality of plate tectonics, and nowhere is this more chaotic than the Ring of Fire.

If you look at a map of the Pacific Ocean, you’ll see a horseshoe-shaped string of volcanoes and deep-sea trenches stretching about 25,000 miles. It isn’t just a catchy name from a Johnny Cash song. It’s the most geologically active zone on Earth. Honestly, about 90% of the world's earthquakes happen here. Think about that. Nearly every major shake, every devastating tsunami, and almost every massive volcanic eruption you’ve ever seen on the news likely traces back to this specific boundary.

What’s Actually Happening Under Your Feet?

Most people think of the Earth’s crust as a single, solid shell. It’s more like a cracked eggshell. These pieces—the tectonic plates—are constantly moving because of the heat churning deep inside the Earth’s mantle. This process, known as mantle convection, is like a giant pot of boiling soup where the hot stuff rises and the cooler stuff sinks.

But it’s the edges where things get weird.

Subduction: The Great Meat Grinder

The Ring of Fire is dominated by subduction zones. This is where one plate—usually a heavy oceanic plate—gets forced down into the hot mantle by a lighter continental plate. It’s not a smooth process. It’s a grinding, sticking, tension-building nightmare.

Imagine pushing two bricks past each other while they’re covered in sandpaper. They stick. You keep pushing. The tension builds until—snap. That "snap" is an earthquake. When this happens under the ocean, it displaces massive amounts of water, which is how we get tsunamis like the 2011 Tōhoku disaster in Japan.

As that lower plate sinks, it carries water and minerals with it. This lowers the melting point of the surrounding rock, creating magma that rises to the surface. Boom. You’ve got a volcano. This explains why places like the Andes in South America, the Cascades in the Pacific Northwest, and the Aleutian Islands in Alaska are basically just long lines of fire-breathing mountains.

The Pacific Plate Isn't Alone

While we call it the Ring of Fire, it’s actually a collaborative effort between several massive players. You have the Pacific Plate, which is the big one in the middle, but it’s constantly wrestling with the Nazca Plate, the North American Plate, the Philippine Sea Plate, and the Indo-Australian Plate.

💡 You might also like: Blue Parrot Inn Key West FL: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s a global game of bumper cars.

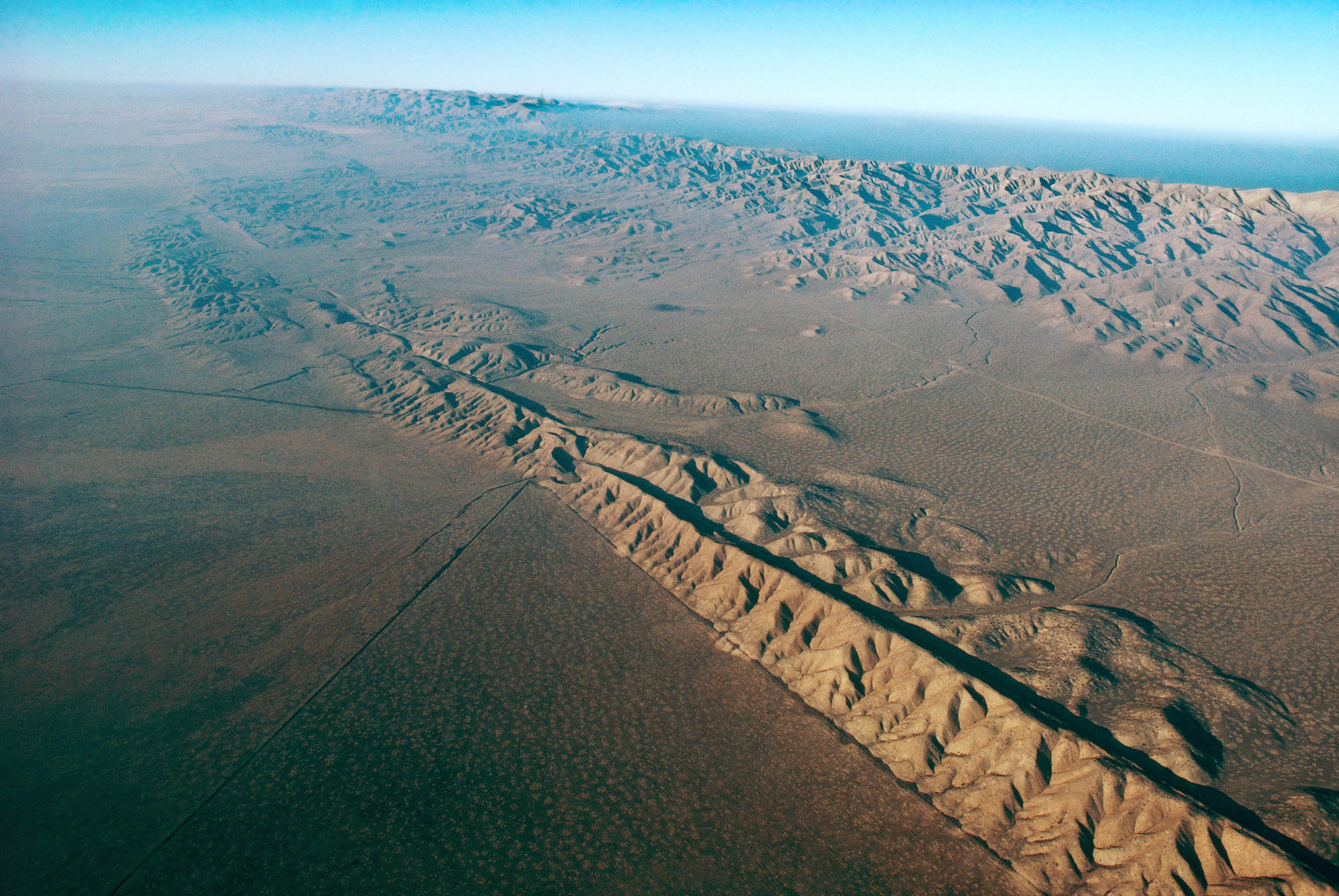

Take the San Andreas Fault in California. People always talk about it "falling into the ocean," which is total nonsense. The San Andreas is a transform boundary. The plates are sliding horizontally past each other. The Pacific Plate is moving north, and the North American Plate is moving south (relatively). They’ve been stuck for a while. Geologists like Lucy Jones have spent decades trying to help the public understand that "The Big One" isn't a myth—it's a mathematical certainty based on how much stress has accumulated along those jagged rock faces.

Why Some Volcanoes Explode and Others Just Leak

There is a huge difference between the volcanoes in Hawaii and the ones in the Ring of Fire. Hawaii sits over a "hotspot," which is basically a blowtorch of magma punching through the middle of a plate. The lava there is runny. It flows like maple syrup.

But the volcanoes created by plate tectonics in the Ring of Fire? They’re different. Because they involve melting crustal rock and water, the magma is thick and "sticky" (high viscosity). It traps gas. When the pressure gets too high, it doesn't flow; it explodes. Think Mount St. Helens in 1980 or Mount Pinatubo in 1991. These are stratovolcanoes, and they are the reason why living near the Pacific rim requires constant monitoring from organizations like the USGS and the Global Volcanism Program.

The Mariana Trench: The Deepest Scar

You can't talk about these movements without mentioning the Mariana Trench. It’s the deepest part of the ocean, nearly 7 miles down. It exists solely because the Pacific Plate is being shoved underneath the smaller Philippine Plate. It is a literal scar on the planet’s surface.

Pressure at the bottom is over 1,000 times the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level. Only a handful of people, including James Cameron and Victor Vescovo, have actually been down there. It’s a reminder that plate tectonics doesn't just build mountains; it creates voids so deep we can barely fathom them.

Is the Earth Growing or Shrinking?

Neither, really. It’s a recycling program.

✨ Don't miss: Ohio Weather: What Most People Get Wrong

While the Ring of Fire is busy destroying old crust through subduction, the Atlantic Ocean is doing the opposite. At the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, plates are pulling apart. Magma rises to fill the gap, cooling into brand-new seafloor. This is called seafloor spreading.

The Earth is basically a conveyor belt.

- New crust is born in the middle of the Atlantic.

- Old crust dies in the trenches of the Pacific.

- The continents just hitch a ride on top.

This cycle, known as the Wilson Cycle, suggests that every few hundred million years, the continents all smash back together into a supercontinent, like Pangea, before ripping apart again. We are currently in the "ripping apart" phase.

What Most People Get Wrong About Earthquakes

There’s a common myth that "earthquake weather" exists—that hot, still days lead to tremors. Science says no. Earthquakes happen miles underground; they don't care about the humidity in Los Angeles.

Another misconception is that we can predict exactly when a plate will slip. We can't. We can calculate probabilities. We can say there’s a 70% chance of a major event in a certain area over the next 30 years, but we can't give you a date and time. The friction between plates is too inconsistent to model perfectly.

Living With the Ring of Fire

If you live in Vancouver, Seattle, Tokyo, or Santiago, you are living on the edge of a geological war zone. It’s beautiful, sure. The mountains are stunning. But the price of that beauty is vigilance.

Infrastructure in these areas is now built with "seismic isolation"—basically putting buildings on giant shock absorbers. Japan is the world leader in this. Their skyscrapers are designed to sway like trees in the wind rather than snapping. Without our understanding of plate tectonics, these cities would be death traps.

How to Prepare for the Unavoidable

You can't stop a tectonic plate. You can only get out of its way or build better. If you find yourself traveling to or living in the Ring of Fire, there are actual, non-boring steps you should take:

- Map your local hazards. Use the USGS Earthquake Hazards map or your local equivalent. Know if you are on "liquefaction" soil—that’s ground that turns to soup during a shake.

- Learn the Tsunami Signs. If you’re at the beach and the water suddenly recedes far out, exposing the seafloor, don't go look at the fish. Run for high ground immediately. That is the ocean "drawing back" before it surges.

- Secure your space. Most injuries in earthquakes aren't from collapsing buildings; they're from heavy furniture and TVs falling on people. Bolt your stuff to the wall.

- Download Early Warning Apps. Apps like ShakeAlert (in the US) can give you a few seconds of warning. It doesn’t sound like much, but it’s enough time to drop, cover, and hold on before the heavy waves hit.

The Earth is an engine. It’s alive, it’s hot, and it’s moving. We’re just the passengers. Understanding the mechanics of plate tectonics and the sheer power of the Ring of Fire won't stop the next big event, but it definitely beats being caught off guard when the ground decides to move.