Imagine standing in a field in Shaanxi Province, China. It’s quiet. Under your feet, there isn’t just dirt; there is a literal subterranean empire that has remained largely unvisited for over two millennia. Most people know about the Terracotta Army, those stiff, clay soldiers standing in formation, but that’s basically just the lobby of the Qin Shi Huang Di tomb. The actual burial chamber of China's first emperor is a completely different beast, and honestly, we might never see the inside of it.

It’s huge.

Archaeologists estimate the entire necropolis covers about 22 square miles. To put that in perspective, that’s larger than the island of Manhattan. You’ve got an emperor who didn’t just want a grave; he wanted a functional city for the afterlife, complete with stables, offices, and armor for his ghostly troops. But the centerpiece—the actual mound where Qin Shi Huang Di is supposedly resting—remains sealed.

The Mercury Problem and the Rivers of Death

If you ask a random person why we haven't opened the Qin Shi Huang Di tomb, they might guess it’s out of respect. That’s part of it. But the real reason is way more "Indiana Jones" than most people realize. Ancient texts, specifically the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian) written by Sima Qian about a century after the emperor died, claim the tomb is filled with mechanical traps and literal rivers of liquid mercury.

Sima Qian described "rivers of mercury" made to flow mechanically to mimic the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers. For a long time, historians thought this was just a colorful metaphor or a tall tale meant to make the emperor sound more god-like.

They were wrong.

In the early 2000s, researchers like Duan Qingbo of the Shaanxi Institute of Archaeology conducted soil tests on the mound. They found mercury levels that were roughly 100 times higher than naturally occurring levels in the area. It’s a toxic soup in there. Opening it without a massive, hermetically sealed containment system would basically create a localized environmental disaster. Plus, mercury vapor is incredibly deadly. One breath of that 2,000-year-old air could be your last.

🔗 Read more: Pic of Spain Flag: Why You Probably Have the Wrong One and What the Symbols Actually Mean

Why the Terracotta Army is Just a Fraction of the Story

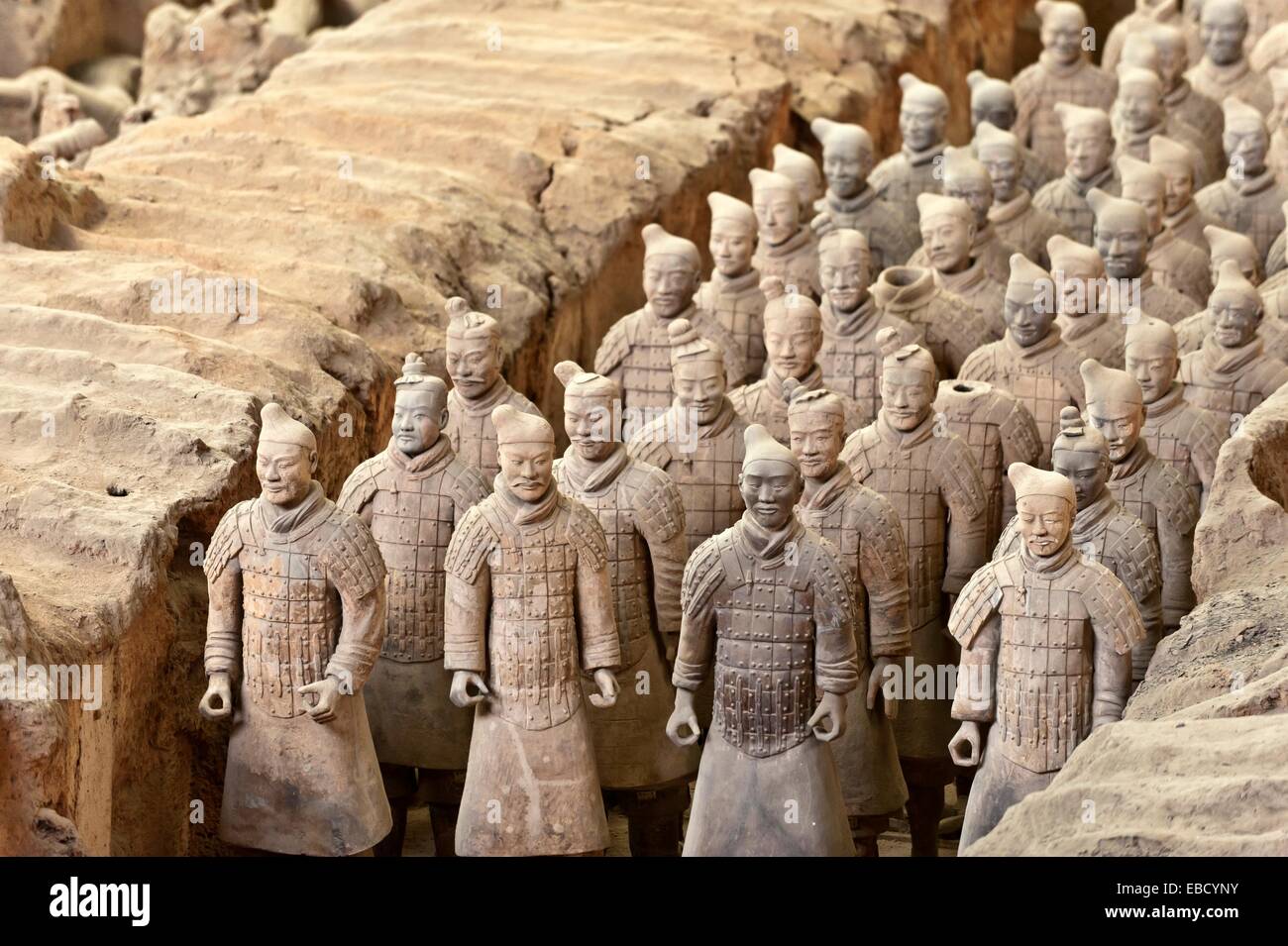

We’ve found over 8,000 soldiers so far. They’re impressive, sure. But they were found nearly a mile away from the actual tomb mound. They were the outer perimeter.

- Every face is different.

- They were originally painted in neon-bright pinks, reds, and blues.

- The moment they were unearthed, the oxygen hit the pigment and it flaked off in seconds.

This "color loss" is a huge deterrent for further excavation. The Chinese government is understandably hesitant to open the main chamber until technology catches up. They don't want to ruin the greatest archaeological find of the century just because they were impatient.

The craftsmanship is honestly terrifying when you think about the logistics. Qin Shi Huang Di unified China in 221 BCE. He started building this tomb long before that. Thousands of laborers—many of whom were essentially enslaved—worked on this for decades. Some didn't make it out. There are mass graves nearby filled with the remains of the workers who knew too much about the tomb's internal layout.

Booby Traps: Myth or Reality?

Sima Qian mentioned "automatically triggered crossbows" designed to shoot anyone who entered. In 2026, we tend to think of ancient tech as primitive, but the Qin Dynasty was surprisingly advanced in metallurgy. We’ve found chrome-plated swords in the pits that are still sharp today. If they could figure out rust-proofing, could they figure out a tripwire?

Maybe.

The wood would likely have rotted by now, but the bronze mechanisms? Those could still be functional. Even if the bows don't fire, the psychological weight of knowing you're walking into a space designed to kill you is enough to give any modern researcher pause.

💡 You might also like: Seeing Universal Studios Orlando from Above: What the Maps Don't Tell You

The Political and Cultural Sensitivity

You can't just dig up the founder of China like it's a backyard garden project. There is an immense amount of cultural weight tied to the Qin Shi Huang Di tomb. He is the man who gave China its name, its script, and its weights and measures. To the Chinese government, this isn't just a site; it’s a sacred piece of national identity.

UNESCO named it a World Heritage site in 1987, which adds another layer of red tape. Every move has to be scrutinized. It's not just about what's inside; it's about how we protect it for the next thousand years.

What Is Actually Inside the Mound?

If we believe the historical accounts, the ceiling is a map of the heavens, encrusted with pearls to represent stars. The floor is a map of the Earth. It’s a microcosm of the entire world as it was understood in 210 BCE.

There are also reports of "ever-burning lamps" fueled by whale oil. While the "ever-burning" part is scientifically impossible (oxygen runs out), the sheer opulence described is staggering. We're talking about gold and silver everywhere.

Modern Tech Is Peeking Through the Walls

We aren't totally blind. Archaeologists have used remote sensing, ground-penetrating radar, and 3D magnetic scans to map the interior without digging.

- They’ve confirmed a massive wall surrounding the central chamber.

- They’ve identified a sophisticated drainage system that has kept the tomb from collapsing due to groundwater for over 2,000 years.

- They found a "high-tech" (for the time) heating system that might have been used to dry the plaster during construction.

It’s a masterclass in ancient engineering.

📖 Related: How Long Ago Did the Titanic Sink? The Real Timeline of History's Most Famous Shipwreck

The Next Steps for Archaeology

So, what happens next? We wait.

The focus right now isn't on digging deeper into the Qin Shi Huang Di tomb, but on preserving what has already been pulled out. Scientists are working on "re-colorizing" the soldiers and using Muon tomography—a technique that uses cosmic ray particles to "see" through solid rock—to get a better picture of the central chamber.

If you’re planning to visit, don't expect to see the Emperor's face. You'll see the pits, the museum, and the massive, grass-covered mound in the distance. It’s a haunting reminder that some things are better left buried until we're actually ready to handle the truth of what's inside.

Practical Insights for the History Obsessed:

- Travel Tip: If you visit Xi'an, go to the museum early. The crowds are no joke, and the scale of the pits is much easier to appreciate when you aren't being elbowed by a tour group.

- Stay Updated: Follow the Shaanxi Academy of Archaeology’s digital archives. They occasionally release 3D scans of newly restored artifacts that never make it to the general public displays.

- Context is Key: Read a translation of Sima Qian's Shiji before you go. Knowing the "official" story makes seeing the physical evidence much more impactful.

- Manage Expectations: You will see the mound, but you won't see the tomb. Understand that the mystery is part of the experience.

The Qin Shi Huang Di tomb remains the world's greatest unopened gift. Whether it's the mercury, the traps, or the sheer political weight of the site, it stays sealed. For now, we just have the terracotta ghosts to tell us the story.

Actionable Steps for Further Exploration

- Review the Science: Look into the 2023 Muon tomography studies conducted on the tomb mound, which provide the most recent "internal" look without physical excavation.

- Explore the Museum Virtually: Many of the high-resolution 3D models of the bronze chariots found near the tomb are available via the Emperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum official website.

- Compare the Dynasties: To understand why this tomb is unique, research the Han Dynasty tombs that followed; they moved away from this level of megalomania toward more modest (but still massive) burials.