Mel Brooks was terrified. Honestly, he had every reason to be. Imagine trying to sell a comedy centered around a flamboyant musical tribute to Adolf Hitler just twenty years after World War II ended. It sounds like career suicide. It nearly was.

The Producers 1968 movie is a miracle of survival. Before it became a Broadway juggernaut or a shiny 2005 remake, it was a scrappy, offensive, and dangerously funny indie flick that almost got buried by its own studio. People forget that back in the late sixties, the idea of "Springtime for Hitler" wasn't just edgy—it was considered a legitimate threat to public taste.

The Scams, The Suits, and Zero Mostel

The plot is basically a masterclass in beautiful desperation. Max Bialystock, played by the toweringly chaotic Zero Mostel, is a washed-up Broadway producer who survives by wooing elderly women out of their checks. He’s a "theatrical jungle cat" in a tattered velvet jacket. Then enters Leopold Bloom. Gene Wilder—with his frizzy hair and blue blanket—is the perfect neurotic foil.

The math is simple.

A producer can make more money with a flop than with a hit. You raise two million dollars, spend a fraction of it on a garbage show, and when it closes on opening night, you pocket the rest. No one audits a failure.

It’s a brilliant business plan for people who have nothing left to lose.

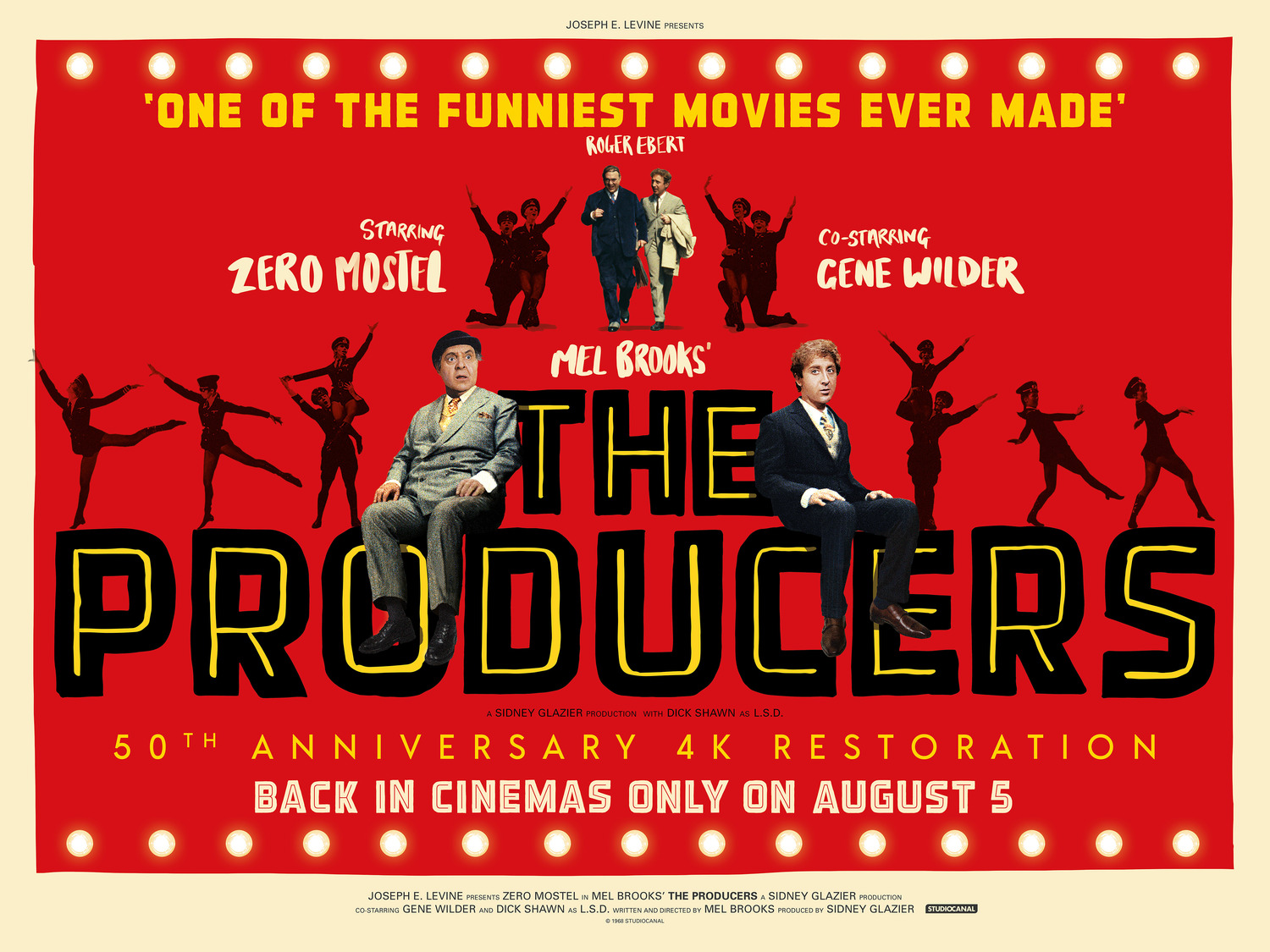

Brooks originally wanted to call it Springtime for Hitler. Joseph E. Levine, the mogul at Embassy Pictures, looked at him like he was insane. Levine refused. He told Brooks that no one would buy a ticket to a movie with Hitler’s name in the title unless it was a documentary. So, we got The Producers. But the core remained: find the worst play ever written, hire the worst director, and cast the worst actor.

Enter Franz Liebkind.

Kenneth Mars played the pigeon-loving, helmet-wearing Nazi playwright with a terrifying level of commitment. His play, Springtime for Hitler: A Gay Romp with Adolf and Eva at Berchtesgaden, was supposed to be the nail in the coffin. It was meant to be so vile that the audience would leave by intermission.

Why the Casting Almost Failed

Did you know Dustin Hoffman was originally supposed to play Liebkind? He was all set. Then, at the very last second, he got a call about a little movie called The Graduate. He begged Mel Brooks to let him out of his contract. Brooks, being a mensch, let him go.

✨ Don't miss: Elaine Cassidy Movies and TV Shows: Why This Irish Icon Is Still Everywhere

If Hoffman stays, the movie changes. Mars brought a specific, unhinged energy that anchored the absurdity.

And then there’s Gene Wilder. This was his breakout. That scene in the fountain where he screams "I’m in bloom!" wasn't just scripted joy; it was the birth of a comedy legend. Wilder had this way of making panic look like high art. He and Mostel didn't just act together; they collided. Mostel was a force of nature, a man who actually lived through the Hollywood blacklist and brought all that resentment and fire to the screen.

The Battle to Get it Distributed

The Producers 1968 movie didn't just walk into theaters. It was shoved into a dark corner.

After seeing the final cut, the executives at Embassy Pictures were horrified. They thought it was disgusting. They literally didn't want to release it. It sat on a shelf for months. It might have stayed there forever if it weren't for Peter Sellers.

Sellers happened to see a private screening of the film. He loved it so much that he took out two full-page advertisements in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter praising the film as one of the greatest comedies ever made. That changed everything. Suddenly, the "disgusting" movie was "avant-garde."

When it finally opened at the Fine Arts Theater in New York, the reaction was... mixed. Some people walked out. Others stayed and laughed until they couldn't breathe.

The Satire is the Point

People often ask if the movie is offensive. Of course it is. That’s the entire point.

Mel Brooks, a combat engineer in WWII who cleared landmines, had a very specific philosophy: you can't bring these monsters back to life, but you can destroy them with ridicule. By turning Hitler into a high-kicking, "Bad Boy Adolf" caricature played by a dazed hippie (Dick Shawn), Brooks stripped the dictator of his power.

It’s a sophisticated layer of satire that often gets lost in the slapstick. You’re laughing at the Nazis, but you’re also laughing at the greed of the producers who are trying to exploit them.

🔗 Read more: Ebonie Smith Movies and TV Shows: The Child Star Who Actually Made It Out Okay

Technical Grit and 1960s New York

The movie looks crunchy. It feels like 1968 New York—grimy, loud, and slightly unhinged.

The cinematography isn't trying to be pretty. It’s claustrophobic. Most of the scenes take place in Max’s office, which feels like a tomb for a career that died in 1945. When we finally get to the theater for the "Springtime for Hitler" number, the transition from the brown, dusty office to the bright, garish stage is jarring.

That opening number is a masterpiece of production design. The rotating swastika formation? The showgirls wearing pretzels and beer steins on their heads? It’s a perfect parody of the Ziegfeld Follies. It’s too much. It’s exactly the kind of over-the-top spectacle that a hack like Max Bialystock would think is "classy."

The script is tight. Brooks won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for a reason. Every line serves a purpose.

"I'm wearing a cardboard belt!"

"Don't be schtupid, be a schmarty, come and join the Nazi Party!"

It’s vulgar, but it’s rhythmic. It’s Yiddish vaudeville meets 1960s cynicism.

The Legacy of a Flop About a Flop

Eventually, the movie found its audience. It became a cult classic. Then it became a Broadway phenomenon that won a record-breaking 12 Tony Awards. But the original film remains the purest version of the story.

It doesn't have the polish of the 2005 version. It’s better because of it.

💡 You might also like: Eazy-E: The Business Genius and Street Legend Most People Get Wrong

The Producers 1968 movie captures a specific moment in time when comedy was shifting. We were moving away from the safe, family-friendly humor of the fifties into something darker and more confrontational. It paved the way for Blazing Saddles, Monty Python, and eventually South Park.

It taught us that nothing is sacred. If you can make people laugh at the worst thing imaginable, you've won.

Real-World Takeaways for Film Buffs

If you’re going back to watch it today, keep an eye on the background. The movie is packed with small details that show just how desperate Max really is. Look at the play posters on his wall—they’re all real-sounding failures.

Also, pay attention to the sound design. The way the silence hangs after the first few lines of "Springtime for Hitler" is performed for the audience in the film. That silence is the loudest thing in the movie. It’s the sound of a thousand people simultaneously realizing they might be going to hell for being there.

Then, one guy laughs. Then another.

That’s the secret of the movie. It’s about the infectious nature of absurdity.

How to Appreciate it Today

- Watch it for the performance of Zero Mostel. Modern acting is often subtle. Mostel is the opposite of subtle. He is a gargoyle come to life. His physical comedy is unmatched—watch how he uses his entire body to sweat, plead, and scheme.

- Ignore the 2005 remake for a second. While Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick are great, they are playing characters. Mostel and Wilder were those people. The 1968 version feels dangerous in a way the musical doesn't.

- Contextualize the "Edginess." Don't just look at it as a "Nazi joke." Look at it as a film made by Jewish artists barely two decades after the Holocaust. It is an act of reclamation.

- Look for the "LSD" Character. Dick Shawn’s portrayal of Lorenzo St. DuBois (L.S.D.) is a fascinating time capsule of the late sixties hippie movement. He’s a "beatnik" Hitler. It shouldn't work, but his utter confusion about where he is makes it hilarious.

The Producers 1968 movie reminds us that the best art often comes from the brink of disaster. Mel Brooks had no money, a controversial script, and a studio that hated him. He turned that friction into a diamond.

If you want to understand modern comedy, you have to start here. You have to see the man in the cardboard belt. You have to hear the "Springtime" melody. Most importantly, you have to realize that sometimes, the only way to deal with a tragedy is to turn it into a farce.

Next time you're scrolling through a streaming service, don't look for something "safe." Look for the movie that almost got burned because it was too funny for its own good. That's where the real magic is.

Actionable Insights for Movie Historians:

- Primary Source Check: Read Mel Brooks' autobiography, All About Me!, specifically the chapters on the 1967-1968 production cycle. He details the specific legal threats he faced during filming.

- Viewing Order: Watch the 1968 film first, then the 2001 Broadway cast recording (available on various platforms), and finally the 2005 film. Notice how the jokes evolved from "shocker" humor to "theatrical" humor.

- Analyze the Satire: Compare the depiction of Hitler in The Producers to Charlie Chaplin’s in The Great Dictator (1940). Notice how the approach to parody changed once the full extent of the war was known.