January 12, 2010. It was a Tuesday. At 4:53 p.m., the ground beneath Haiti didn't just shake; it essentially buckled. For roughly 35 seconds, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake turned the capital city into a literal graveyard of concrete and rebar. Most people think they know what happened next—the news reports, the celebrity telethons, the massive influx of aid—but the reality of the Port-au-Prince 2010 earthquake is a lot messier, and frankly, more tragic than the headlines suggested.

It wasn't just a natural disaster. It was an infrastructure failure.

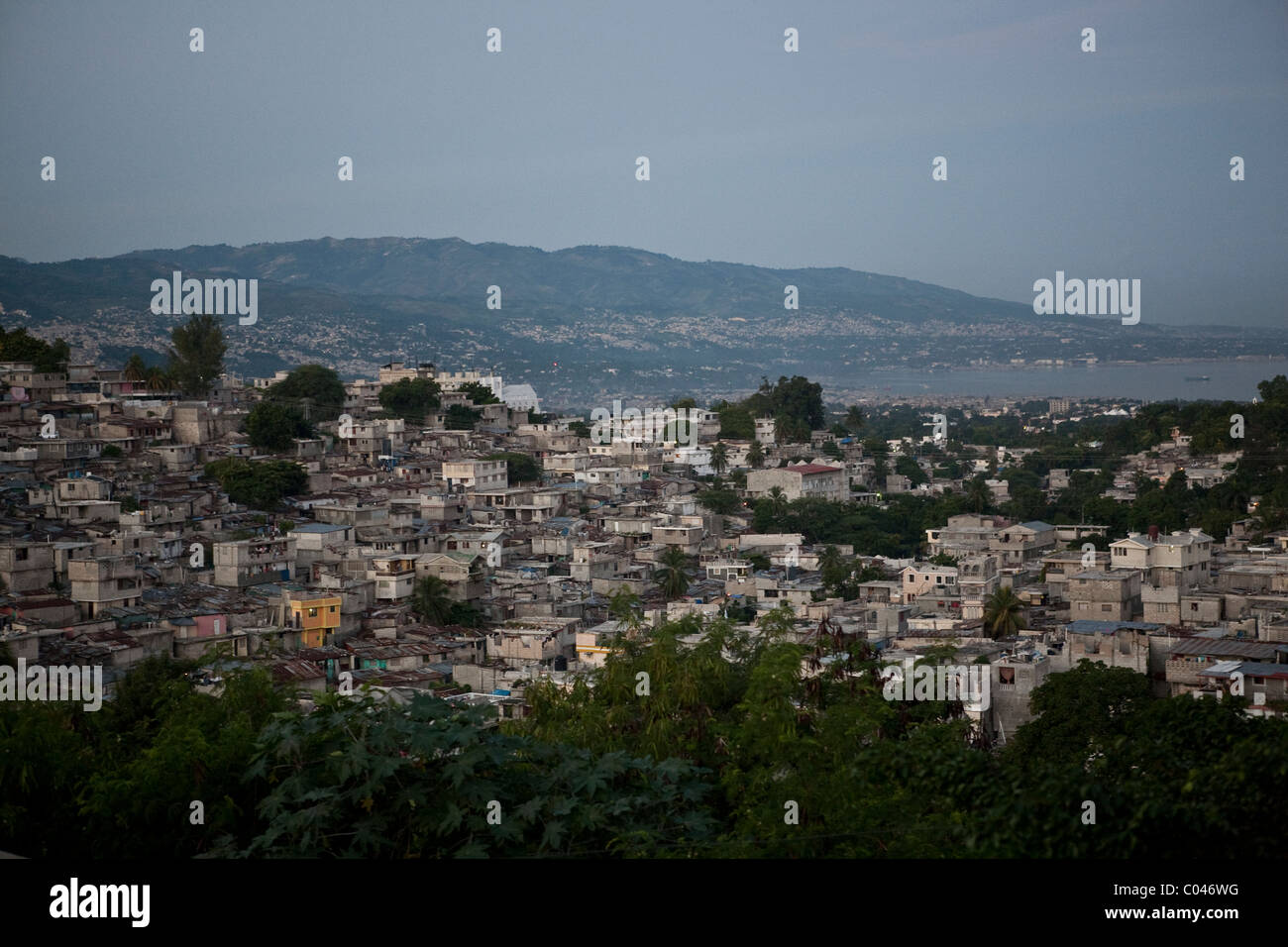

The epicenter was near Léogâne, just 16 miles west of the capital. Because the quake was shallow—only about 8 miles deep—the energy release was focused and brutal. Port-au-Prince wasn't built for this. Not even close. You had thousands of people living in cinderblock homes perched on steep, unstable hillsides. When the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault system finally slipped after 250 years of dormant tension, those houses became deathtraps.

The numbers that don't tell the whole story

Estimating the death toll of the Port-au-Prince 2010 earthquake is actually a point of massive contention. The Haitian government eventually claimed over 300,000 people died. Other reports, like those from the US Agency for International Development (USAID), suggested the number might have been closer to 100,000 or 150,000.

Does the specific number matter when you're looking at mass graves? Probably not to the survivors.

But it matters for data. For history.

🔗 Read more: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

Beyond the deaths, 1.5 million people were left homeless. Imagine the entire population of a major American city suddenly living under plastic tarps in the middle of a tropical heatwave. That’s what happened. The National Palace collapsed. The Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption fell. Even the headquarters of the United Nations Stabilization Mission (MINUSTAH) crumbled, killing the mission chief, Hédi Annabi.

If the government can’t protect its own palace, how is it supposed to protect its people? It couldn't. The state basically vanished for weeks.

What actually went wrong with the international response

People donated billions. Literally billions of dollars. You likely remember the "Hope for Haiti Now" telethon. But if you walk through parts of Port-au-Prince today, you’d be forgiven for wondering where that money went.

The recovery from the Port-au-Prince 2010 earthquake became a textbook example of "disaster capitalism" and logistical failure. Money didn't always go to Haitian organizations. Instead, it went to large international NGOs. These groups had high overhead costs. They brought in outside experts who didn't speak Kreyòl. They built houses that nobody wanted to live in because they were too far from jobs.

Then came the cholera.

💡 You might also like: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

This is the part that still makes people angry. UN peacekeepers from Nepal, brought in to help after the quake, inadvertently introduced cholera to the Artibonite River. It wasn't a "natural" part of the disaster. It was brought in by the rescuers. Over 10,000 more people died from the outbreak. It took years for the UN to even admit a shred of responsibility.

The architectural "missing middle"

Haiti has a history of gorgeous, flexible architecture called "Gingerbread houses." These wooden structures, with their high ceilings and latticework, actually survived the quake pretty well. They flexed. They breathed.

The problem was the 20th-century shift to "modern" materials. Concrete is heavy. If you don't use enough rebar, or if you use "salty" sand from the beach to mix your cement (which corrodes the metal), that concrete becomes a heavy lid that collapses in a pancake fashion. That’s why the Port-au-Prince 2010 earthquake was so lethal. It wasn't the shaking that killed people; it was the buildings.

Why we still talk about 2010 today

You can't understand modern Haiti without looking back at 2010. The earthquake broke the back of the country's fragile economy and its political system. It created a power vacuum that gang leaders eventually filled.

When people ask why Haiti hasn't "recovered," they're looking for a simple answer. There isn't one. It’s a mix of bad luck, historical debt (that massive independence debt to France), and a botched international recovery effort that focused on short-term "band-aids" rather than long-term resilience.

📖 Related: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

Also, we have to talk about the "NGO Republic" phenomenon. At one point, there were so many non-profits in Port-au-Prince that the government had no control over its own urban planning. If a charity wants to build a school in a specific spot, they do it. But who pays the teachers? Who maintains the roof in ten years? Often, nobody.

What you should actually take away from this

The Port-au-Prince 2010 earthquake taught us—or should have taught us—that aid without agency is just a temporary fix.

If you're looking to understand how to help in future disasters, or if you're researching the impacts of this specific event, here are the cold, hard realities:

- Local leadership is king. Aid works best when it’s funneled through local community leaders who know who is actually hungry and where the rubble needs to be cleared first.

- Building codes are life and death. Seismic retrofitting isn't just a luxury for rich countries. It’s a basic human right in earthquake zones.

- The "Relief to Development" gap is real. It’s easy to get people to donate water bottles in the first week. It’s nearly impossible to get them to fund a sewage system five years later.

If you’re a student of history or a policy nerd, look into the work of Dr. Paul Farmer and Partners In Health. They were some of the few who actually stayed and built permanent infrastructure, like the University Hospital in Mirebalais. They didn't just drop off boxes; they hired Haitian doctors. That’s the nuance.

Next Steps for Research and Action:

- Audit the Aid: If you're looking into disaster relief, read the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) reports on how the USAID money was actually spent in Haiti. It's eye-opening.

- Support Local Journalism: Follow outlets like The Haitian Times or AyiboPost. They provide the ground-level context that international media usually misses once the "story" gets old.

- Study Seismic Resilience: Look into the "Build Change" initiative. They focus on teaching local masons how to reinforce existing block houses rather than trying to import expensive, foreign housing kits.

The 2010 quake wasn't a one-off event. It was a turning point. We owe it to the victims to actually learn why the recovery failed as much as the earth shook.