You've seen them. Maybe it’s a bloated elephant trying to balance on a tightrope or a stubborn donkey kicking over a bucket of "bipartisanship." These drawings are everywhere. They're quick. They're often mean. And honestly, they're probably the most effective way we process the absolute chaos of modern governance. A political parties political cartoon isn't just a doodle in the corner of a newspaper or a quick-scrolling meme on your feed; it is a concentrated dose of visual rhetoric that hits harder than a 2,000-word op-ed ever could.

Think about it. We live in a world of 24-hour news cycles and endless Twitter (or X) threads. Nobody has time to read a policy white paper. But everyone has three seconds to look at a drawing of a Republican and a Democrat fighting over a steering wheel while the car goes off a cliff. That’s the power. It simplifies the complex. It turns abstract legislative battles into a playground scrap.

The Men Who Drew Our Modern Mess

We kinda have to talk about Thomas Nast. If you're looking for the "Godfather" of this stuff, he’s your guy. Back in the 19th century, he was working for Harper’s Weekly, and he basically invented the visual language we still use today. He didn't just draw the Republican elephant; he popularized it in his 1874 cartoon "Third Term Panic." He took a donkey—which had been associated with Andrew Jackson decades earlier—and cemented it as the symbol for the Democrats.

Nast wasn't just "illustrating." He was a hatchet man. He used his pen to take down William "Boss" Tweed and the Tammany Hall political machine in New York. Tweed famously said, "I don't care a straw for your newspaper articles; my constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damned pictures!" That is the core of the political parties political cartoon. It bypasses the literacy of policy and goes straight for the gut.

It’s brutal.

But it’s also remarkably consistent. You look at a cartoon from 1880 and one from 2026, and the tropes are identical. The parties are always depicted as animals, or perhaps as bickering spouses, or as two halves of a monster that can't decide which way to walk.

Symbols are Shortcuts for Our Brains

Why do we keep using the same icons? Why does every cartoonist reach for the donkey and elephant?

👉 See also: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

It’s about cognitive shorthand. When you see those ears or that trunk, your brain instantly loads a massive file of associations: taxes, social issues, foreign policy, and every headline you’ve seen in the last six months. Cartoonists like Herb Block (Herblock) or Pat Oliphant mastered this. They didn't have to explain who the characters were. They just had to show the symbol.

- The Donkey: Usually shown as stubborn, sometimes small, often fractured or fighting itself.

- The Elephant: Often depicted as clumsy, massive, or prone to "forgetting" its own promises despite the "elephants never forget" trope.

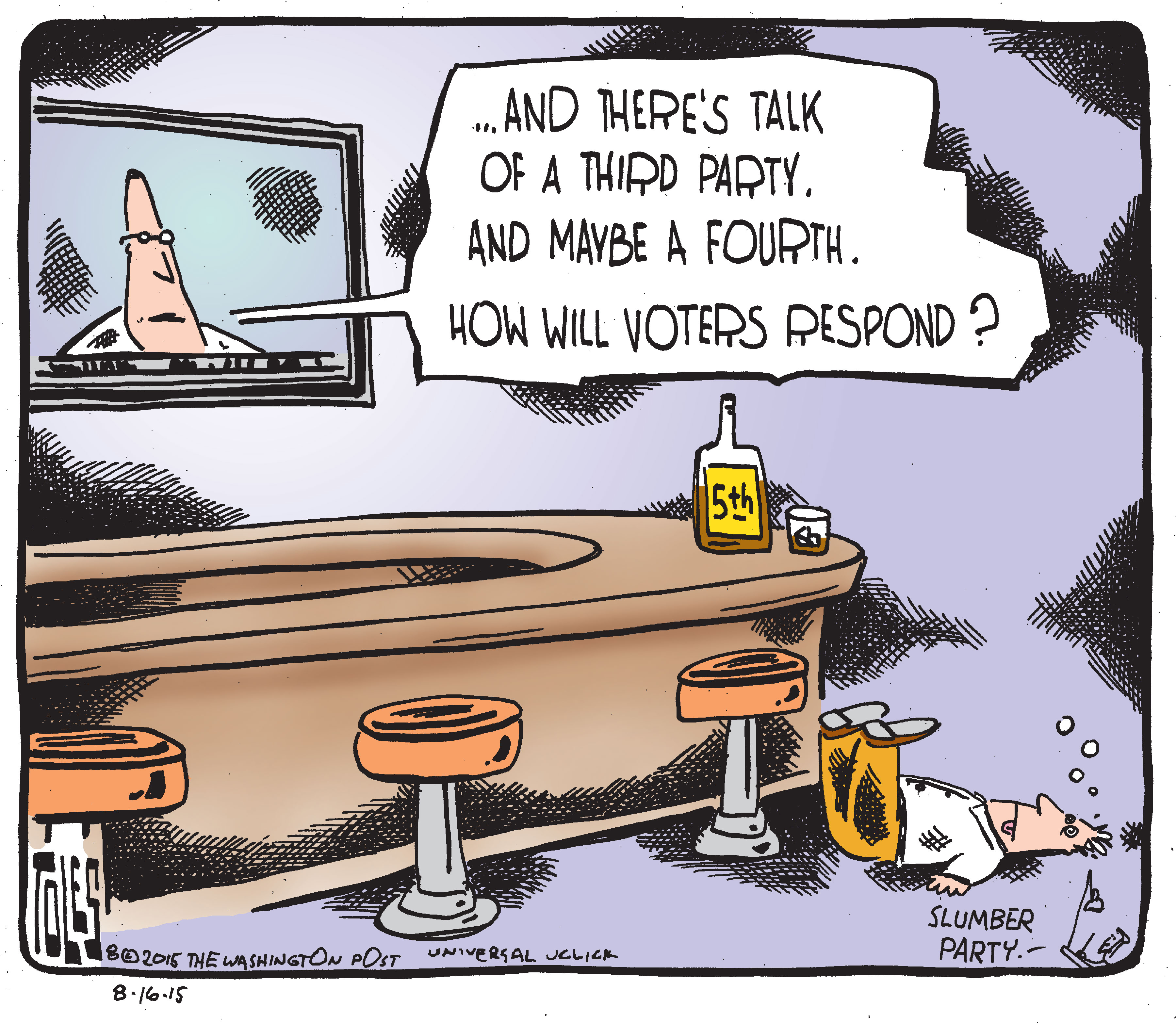

But there’s a darker side to this. By reducing complex human organizations—made of millions of diverse voters—into two distinct, often ugly animals, these cartoons reinforce the "us vs. them" mentality. They create a binary. If the elephant is the villain today, the donkey must be the hero, and vice versa. There is rarely room for a third animal in the pen. This visual polarization reflects (and sometimes drives) the actual polarization in Washington.

The Shift From Paper to Pixels

Let’s be real: the traditional newspaper staff cartoonist is a dying breed. It’s sad, but true. In the mid-20th century, almost every major city paper had a dedicated artist. Now? Not so much. But that doesn’t mean the political parties political cartoon is dead. It just moved.

It’s on Instagram. It’s on TikTok. It’s in the form of "political memes."

The format has changed from meticulously cross-hatched ink drawings to high-contrast digital images. The goal, however, remains exactly the same: mockery. A cartoon by someone like Matt Wuerker at Politico or Michael Ramirez can go viral in minutes. They provide a "vibe check" for the party faithful. If you’re a Democrat and you see a cartoon mocking the Republican leadership's latest gaffe, you share it. It validates your worldview.

This leads to a weird echo chamber effect. In the "old days," you’d see the cartoon in a general-interest newspaper. You might disagree with it, but you saw it. Today, algorithms ensure you mostly see cartoons that mock the party you already hate. It’s like a digital dopamine hit of confirmation bias.

✨ Don't miss: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

[Image showing a comparison between a 19th-century hand-drawn political cartoon and a 21st-century digital political meme]

When Satire Crosses the Line

Is there a limit? Sometimes.

Political cartooning is, by nature, an art of exaggeration. You take someone’s nose and make it huge. You take a party’s platform and make it look like a suicide pact. But throughout history, this has veered into territory that people find genuinely offensive. We’ve seen cartoons that lean on lazy stereotypes or dehumanizing imagery.

There’s a tension there. On one hand, you have the "First Amendment" defense. Satire is protected. On the other, you have a public that is increasingly sensitive to how marginalized groups are portrayed within the context of party politics. When a political parties political cartoon targets a specific politician, it’s one thing. When it targets an entire demographic that associates with a party, things get messy.

Critics like Dr. Catherine Knight Steele have pointed out how visual rhetoric in politics often carries baggage from past eras of discrimination. Even the "simple" donkey and elephant can be manipulated to carry racist or classist undertones if the artist isn't careful—or even if they are being intentionally provocative.

How to Read a Cartoon Without Getting Fooled

Since these images are designed to manipulate your emotions, you have to approach them with a bit of a "detective" mindset. Don't just laugh or get angry. Look at the mechanics.

🔗 Read more: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

- Check the Caricature: Who is the "main character"? Are they drawn to look human or like a monster? This tells you who the cartoonist wants you to hate.

- Look for the Labels: Cartoonists love labeling things. If a suitcase is labeled "Social Security," it's not just a suitcase. Why did they choose that specific object?

- The Background Noise: Sometimes the real message is in the shadows. Is there a tiny figure in the corner representing "the taxpayer" or "the future"?

- The Source: Who pays the cartoonist? Are they an independent freelancer or are they on the payroll of a specifically partisan outlet?

The Future of the Visual Fight

As we head deeper into the 2020s, AI is starting to creep in. We’re seeing "cartoons" generated by prompts. This is a weird shift. A human cartoonist has a "voice." They have a specific style and a specific set of gripes. An AI-generated political parties political cartoon feels... hollow. It lacks the bite of a human who actually feels the frustration of the current political climate.

But people still crave that human touch. They want the biting wit of a Ben Garrison (if they’re on the right) or a Barry Blitt (if they’re on the left). We want to know a real person is as annoyed as we are.

We also see more "interactive" cartoons. Some digital outlets are experimenting with animations where you can click on different parts of the drawing to see facts or counter-arguments. It’s a way to add depth to a medium that is, by definition, shallow. It bridges the gap between the "three-second look" and actual information.

Actionable Insights for Navigating Political Imagery

Don't let a clever drawing do your thinking for you. Use these steps to stay sharp:

- Diversify your feed. If your social media is only showing you cartoons that mock the party you dislike, manually search for the "other side." You don't have to agree with them, but you should see how they are framing the same issue. It helps you understand the "visual language" of the opposition.

- Trace the history. When you see a symbol you don't recognize, look it up. Many modern cartoons use "visual puns" that refer to events from the 1970s or 80s. Understanding the reference makes the satire clearer.

- Support the artists. If you value the role of satire in democracy, consider subscribing to publications that still employ editorial cartoonists. It’s a specialized skill that requires a deep understanding of both art and policy.

- Check the context. Before you hit "share" on a viral cartoon, check the date. Frequently, cartoons from five or ten years ago are recirculated as if they are about current events. A cartoon about a 2012 budget crisis might look relevant today, but the specifics matter.

- Think about the "Middle Ground." Ask yourself: "What would a cartoon about this issue look like if it didn't take a side?" Often, you'll realize that the most honest cartoon would be one where both symbols are equally at fault, which is a perspective we rarely get in a polarized media environment.

The political parties political cartoon is a survivor. It outlived the printing press, survived the television era, and is currently thriving in the digital age. It’s the ultimate mirror. It shows us the ugliest version of our politics, and in doing so, it occasionally forces us to admit how ridiculous the whole spectacle has become. Keep looking, but keep your eyes open.