Robert Frost is basically the face of New England. You’ve seen the photos. He’s the craggy-faced old man with the white hair, looking like he just stepped off a tractor after a long day of fixing stone walls. Because of that image, a lot of people think the poems of Robert Frost are just greeting card fodder—pleasant little observations about birches and snowy evenings.

That’s a mistake.

If you actually sit with his work, you realize Frost wasn't some Hallmark optimist. He was a guy who dealt with immense personal tragedy, including the death of his wife and four of his six children. That pain leaks into the ink. His "nature" poems aren't really about nature; they're about the terrifying realization that the universe is mostly indifferent to whether you live or die.

The "Road Not Taken" Misunderstanding

Let’s get the big one out of the way. "The Road Not Taken" is probably the most misinterpreted piece of literature in American history. You see it on graduation cards and "hustle culture" Instagram posts all the time. People think it’s an anthem for rugged individualism. "I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference."

Except, if you read the actual lines right before that, Frost explicitly says the two roads were "worn... really about the same" and that they "equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black."

He’s trolling us.

Frost wrote this for his friend Edward Thomas, a man who was notoriously indecisive. The poem isn't about being a rebel; it’s about how humans lie to themselves after the fact. We make a random choice, and then years later, we tell a story about how it was a grand, intentional decision. It’s a poem about the "sigh" of regret and the way we narrate our own lives to feel more in control than we actually are.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Why Frost Loved a Good Wall (And Why He Hated Them Too)

"Mending Wall" is another staple when discussing the poems of Robert Frost. It’s where we get the famous line, "Good fences make good neighbors."

Most people quote that like it’s a piece of wisdom. But in the context of the poem, Frost’s narrator is actually mocking his neighbor for saying it. The narrator is the one asking why they need a wall when there are no cows to keep in. He calls the neighbor an "old-stone savage" who "moves in darkness."

There’s this constant tension in his work between the need for human connection and the stubborn, almost primitive desire to keep people out. He lived in a time of massive transition—the shift from agrarian life to the industrial age—and you can feel that friction in every stanza. He wasn't just writing about rocks; he was writing about the invisible barriers we put between ourselves and the people living twenty feet away.

Nature Doesn't Care About You

There is a specific kind of "Frostian" dread that shows up in his later work. Take "Design," for example. It’s a short poem about a white spider on a white flower holding a white moth.

It sounds pretty, right? It’s not.

Frost asks what "design of darkness to appall" brought these three things together. He’s questioning if there’s a creator at all, or if the world is just a series of random, cruel coincidences. It’s dark stuff. He used the natural world as a mirror for human anxiety. When he writes about a "Design," he’s flirting with the idea that if God exists, He might be kind of a sociopath.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

The Technical Mastery Nobody Notices

Frost was a stickler for form. He famously said that writing free verse—poetry without rhyme or meter—was like "playing tennis without a net." He loved the "net."

He used iambic pentameter because it mimics the natural cadence of American speech. If you listen to a recording of Frost reading, he doesn't sound like a "poet." He sounds like a guy from New Hampshire telling you why his roof is leaking.

- He mastered the "sound of sense."

- He used simple words to hide incredibly complex philosophies.

- His rhymes never feel forced; they feel inevitable.

Take "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." It’s a perfect poem. The rhyme scheme ($AABA$, $BBCB$, $CCDC$, $DDDD$) is tight enough to choke a lesser writer. But it flows so naturally that you don't even notice the technical gymnastics happening behind the scenes. And that ending—repeating "And miles to go before I sleep"—isn't just a sleepy thought. Most scholars, like the late William H. Pritchard, suggest it’s a brush with a "death wish." The woods are "lovely, dark and deep," and the speaker is tempted to just... stop. Forever.

How to Actually Read Frost Today

If you want to get into the poems of Robert Frost without feeling like you're back in 10th-grade English class, stop looking for the "moral." Frost hated morals. He called them "the most unpleasant part of a story."

Instead, look for the "shiver."

Look for the moment where the poem turns from a description of a tree or a bird into a realization about loneliness or the passage of time. He’s much closer to a modern existentialist than he is to a 19th-century Romantic.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Key Collections to Explore:

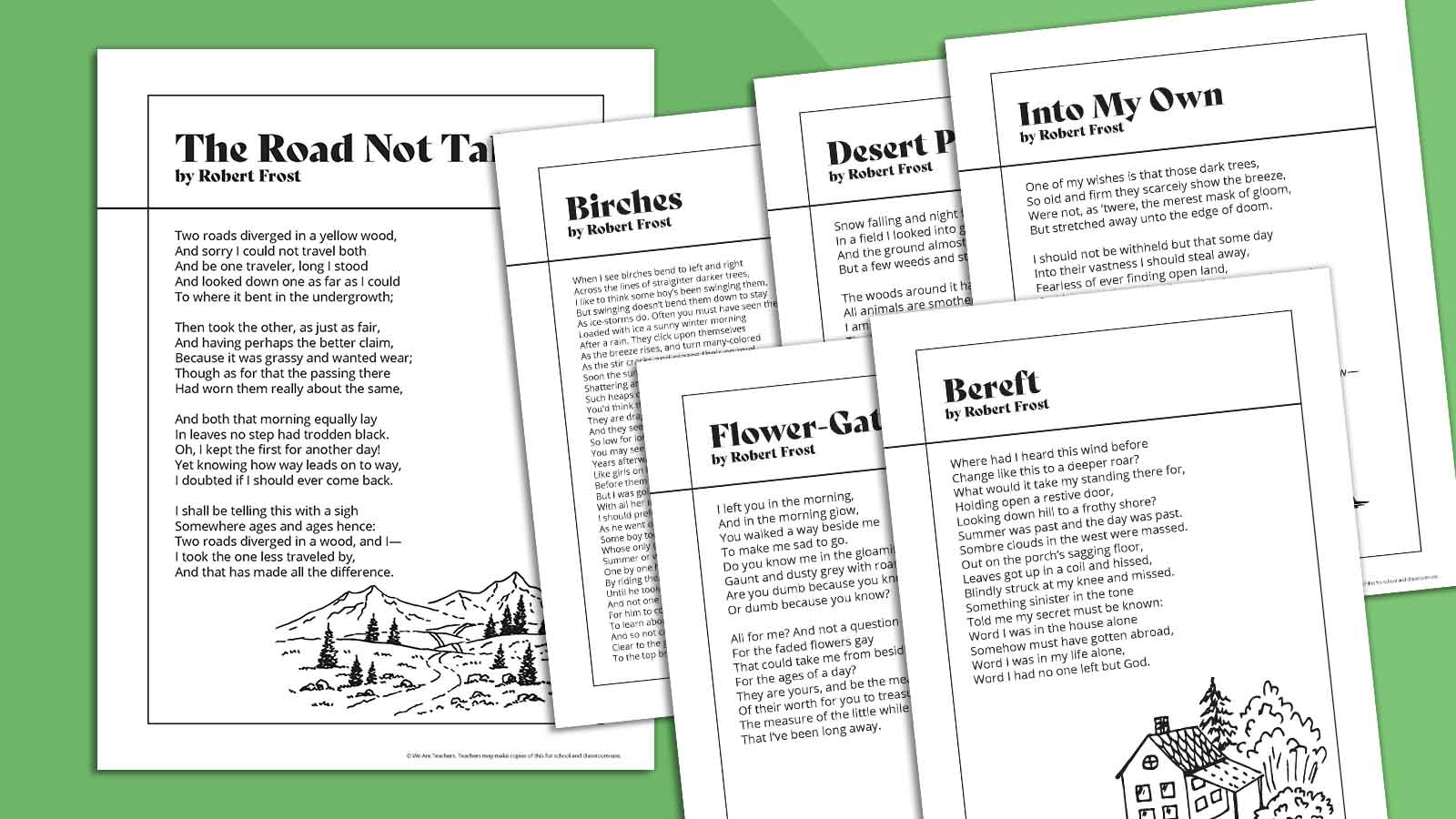

- A Boy’s Will (1913): His first big hit. It’s a bit more traditional but shows the seeds of his later gloom.

- North of Boston (1914): This is where he finds his voice. It’s full of "dialogue poems" like "The Death of the Hired Man" that feel like short plays.

- Mountain Interval (1916): Contains "Birches" and "The Road Not Taken."

Honestly, the best way to experience him is to read him aloud. Frost believed the "ear is the only true writer." If you don't hear the conversational hitch in the lines, you're missing half the point. He’s talking to you. He’s sharing a secret, and usually, that secret is that the world is a lot bigger and a lot scarier than we like to admit.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Frost’s Work

If you're looking to deepen your understanding of these works, don't just stick to the "Best Of" lists.

Start with the "Darker" Poems:

Skip "The Road Not Taken" for a second. Read "Desert Places." It’s a short poem about a snowy field, but it ends with a line about the "spaces between stars" and the "desert places" inside the human soul. It will give you a much better sense of who Frost actually was.

Listen to the Recordings:

The Library of Congress has archival recordings of Frost reading his own work. His voice is dry, a little raspy, and completely devoid of sentimentality. Hearing him read "Provide, Provide" changes the way you see his entire career. He’s cynical, funny, and sharp.

Visit the Robert Frost Stone House:

If you’re ever in Shaftsbury, Vermont, go to the museum. Standing in the room where he wrote "Stopping by Woods" on a hot June morning helps demystify the "winter" poet persona. It reminds you that he was a craftsman at work, not a mystical figure receiving visions from the trees.

Compare the Narratives:

Read "Home Burial." It’s a brutal, heart-wrenching dialogue between a husband and wife who have lost a child. It’s one of the most honest depictions of grief ever written. Compare that to his nature lyrics, and you’ll see that the "woods" were often just a place he went to escape the unbearable reality of his home life.