You just bought a beautiful Japanese Maple. It looks perfect in the nursery, the tag says it’s hardy to your area, and you spend all Saturday digging a hole that’s twice as wide as the root ball. You’re doing everything right. But three years later, a freak cold snap or a weirdly humid summer kills it. Why? It's usually because we treat the planting hardiness zone map like a holy text instead of what it actually is: a rough sketch based on averages that are moving targets.

The USDA released its most recent update to the map in late 2023, and it was a bit of a wake-up call. Roughly half of the United States shifted into a warmer zone. If you were a 6b, you might be a 7a now. That sounds like a small change, right? It’s not. It’s the difference between your figs surviving the winter or turning into mushy sticks.

What the Planting Hardiness Zone Map Actually Measures (And What it Ignores)

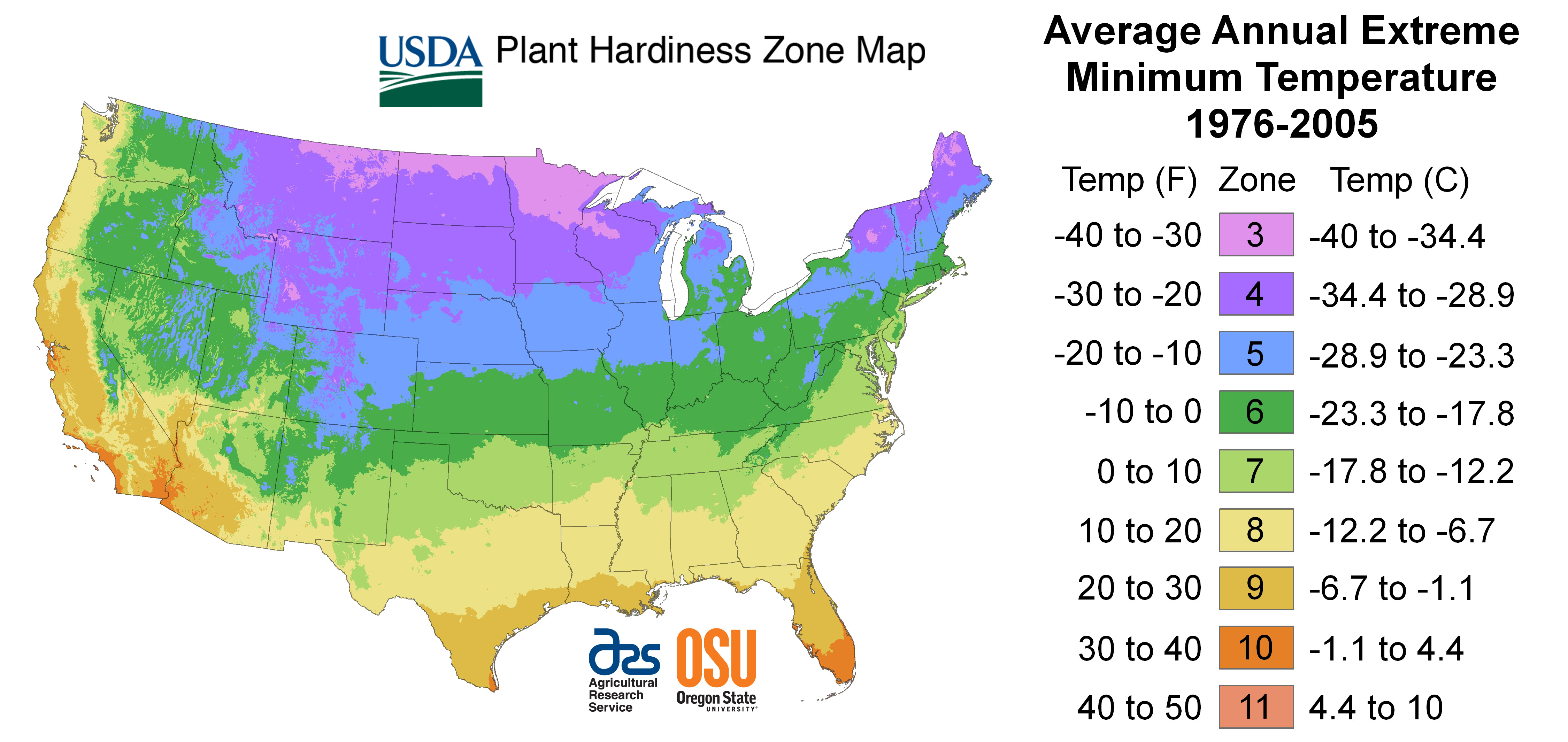

Most people think the map is a weather forecast. It isn’t. The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is strictly based on the average annual extreme minimum winter temperature. Basically, they look at the coldest night of the year over a 30-year period and average those numbers out.

It doesn’t tell you how hot your summers get. It doesn’t tell you about humidity, soil pH, or whether you get 10 inches of rain or 50. This is the biggest trap gardeners fall into. You could live in Zone 8 in Seattle and Zone 8 in Charleston, South Carolina. They have the same average "coldest night," but if you try to grow a Seattle-loving lupine in the swampy heat of a South Carolina July, it’s going to die a fast, crispy death.

Heat matters. Rainfall matters. The map only cares about the frost.

The 2023 Update: Why Your Garden Just "Moved" South

When the 2023 map dropped, scientists used data from 13,625 weather stations. That’s a massive jump from the 2012 version. Because the tech got better, the map got more granular. We now see "microclimates" appearing in cities where the concrete holds onto heat—the urban heat island effect—making downtown areas sometimes a full half-zone warmer than the suburbs just ten miles away.

✨ Don't miss: Deep Wave Short Hair Styles: Why Your Texture Might Be Failing You

If you look at the data from the PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University, who worked with the USDA on this, the trend is clear. The warming isn't just a fluke. The map is literally creeping north. For some of us, this is exciting because it means maybe, just maybe, we can grow those gardenias we’ve always wanted. For others, it’s a warning that our traditional cool-weather crops like peonies might start struggling because they aren't getting enough "chill hours" in the winter to bloom properly.

Understanding the "A" and "B" Subzones

You’ve probably seen labels like 7a or 7b. Each numbered zone represents a 10-degree Fahrenheit range. The "a" and "b" break that down into 5-degree increments.

Zone 7: 0°F to 10°F.

- 7a: 0°F to 5°F

- 7b: 5°F to 10°F

Does five degrees really matter? Ask a rosemary bush. Some varieties of rosemary are rock-solid down to 5 degrees but will give up the ghost the second the thermometer hits zero. If you’re right on the edge, you have to be careful. Honestly, if you’re in a 7a, I’d still buy plants rated for Zone 6 just to have a safety net. Nature doesn't care about averages; it only takes one record-breaking night to reset your garden to zero.

The Problem with "Zone Creep"

We are seeing a phenomenon called zone creep. It's weird. You’ll see birds and insects moving into areas they never used to inhabit because the winters aren't killing them off anymore. This sounds okay until you realize that also applies to pests. Destructive bugs that used to be kept in check by deep freezes are now surviving in northern states.

🔗 Read more: December 12 Birthdays: What the Sagittarius-Capricorn Cusp Really Means for Success

Gardeners in places like Ohio or Pennsylvania are starting to deal with southern pests that were unheard of twenty years ago. The planting hardiness zone map is a tool for survival, but it’s also a map of migration.

Real-World Examples: The Myth of the "Safe" Plant

Let’s talk about the Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla). It’s the one with the big blue or pink "mophead" flowers. These are usually rated for Zone 5 or 6. But here’s the kicker: while the plant might survive a Zone 5 winter, the flower buds often don’t. They grow their buds on "old wood" (last year's stems). If you have a late spring frost—something the hardiness map doesn't account for—those buds freeze and die. You end up with a beautiful green bush that never blooms.

This is why experienced growers look at more than just the number. They look at:

- Last Frost Dates: Usually in April or May.

- First Frost Dates: September or October.

- AHS Heat Zones: This is a separate map that tracks how many days per year the temp goes above 86°F.

If you only use the USDA map, you're only seeing half the picture. It’s like buying a car based only on its top speed without checking if it has brakes.

How to Hack Your Local Microclimate

Your backyard isn't a flat, uniform space. It has "folds" in the climate.

💡 You might also like: Dave's Hot Chicken Waco: Why Everyone is Obsessing Over This Specific Spot

- The South-Facing Wall: This is the warmest spot on your property. Brick or stone walls soak up sunlight all day and radiate it back at night. You can often grow plants here that are one full zone higher than your official rating.

- The Low Spot: Cold air acts like water. It flows downhill and settles in the lowest point of your yard. These "frost pockets" can be 5 to 10 degrees colder than the rest of your garden. Never plant your most delicate fruit trees at the bottom of a hill.

- Windbreaks: A thick evergreen hedge or a fence can shield plants from the "desiccating" (drying out) winter winds. It's often the wind, not the temperature, that kills evergreens in the winter by sucking the moisture out of their needles while the ground is frozen.

Don't Trust the Big Box Store Tags

This is a bit cynical, but it’s true: retailers want to sell plants. Often, you’ll see plants in a nursery that are barely hardy for your zone. They look great in May, but they are "marginal." If you see something labeled "hardy to Zone 7" and you live in Zone 7a, you are gambling.

I’ve seen stores in Zone 6 selling Eucalyptus trees. Sure, they might survive a mild winter, but the first "Polar Vortex" that comes through will turn them into expensive firewood. If you want a garden that lasts decades, always aim to plant things that are hardy to at least one zone colder than where you live. It’s the "sleep better at night" strategy.

Native Plants: The Ultimate Map Bypass

If you’re tired of obsessing over the planting hardiness zone map, look at what’s growing in the local woods. Native plants have spent thousands of years adapting to your specific area's weirdness. They don't just handle the cold; they handle the specific bugs, the specific soil, and the erratic rain cycles of your region.

Doug Tallamy, an entomologist and author of Nature's Best Hope, argues that native plants are the backbone of the ecosystem. They are "hardy" in a way that an imported ornamental never will be. When a freak ice storm hits, the native oaks and viburnums usually shrug it off, while the exotic cherries split in half.

Actionable Steps for Your New Zone

Since the map just changed, you should probably re-evaluate your strategy. Don't just keep doing what you've been doing because "that's how we've always done it."

- Check your new coordinates: Go to the USDA website and plug in your zip code. Don't assume you're the same zone you were five years ago.

- Audit your "Borderline" plants: If you moved from a 6b to a 7a, you might be able to stop heavy mulching for some of your perennials, but don't get cocky. The 30-year average has warmed up, but individual years can still be brutal.

- Watch the soil temperature: Hardiness is often about the roots. A thick layer of wood chips (3-4 inches) can keep the ground from freezing as deep, which can help a "marginal" plant survive a zone it shouldn't.

- Invest in "Season Extenders": If you’re trying to push the limits of your zone, buy some frost blankets or "Wall-o-Water" insulators. They can give you about a 5-10 degree buffer.

- Document everything: Keep a garden journal. Note when your first frost actually happens versus when the map says it should. Your own data is always better than a national average.

The planting hardiness zone map is a fantastic baseline, but it's just the beginning of the conversation between you and your dirt. Use it to narrow down your choices, but use your eyes and your own backyard's history to make the final call. Gardening is a game of probability, and the map just helps you tilt the odds in your favor.