It’s easy to look back at 1960s sci-fi and see nothing but rubber masks and stiff acting. But let's be real—the Planet of the Apes 1968 movie is a different beast entirely. It’s gritty. It’s sweaty. It feels like a fever dream that shouldn't have worked, yet it changed the DNA of Hollywood forever. Most people remember the ending (we’ll get there, obviously), but they forget how weirdly philosophical and biting the social commentary actually was for a big-budget flick.

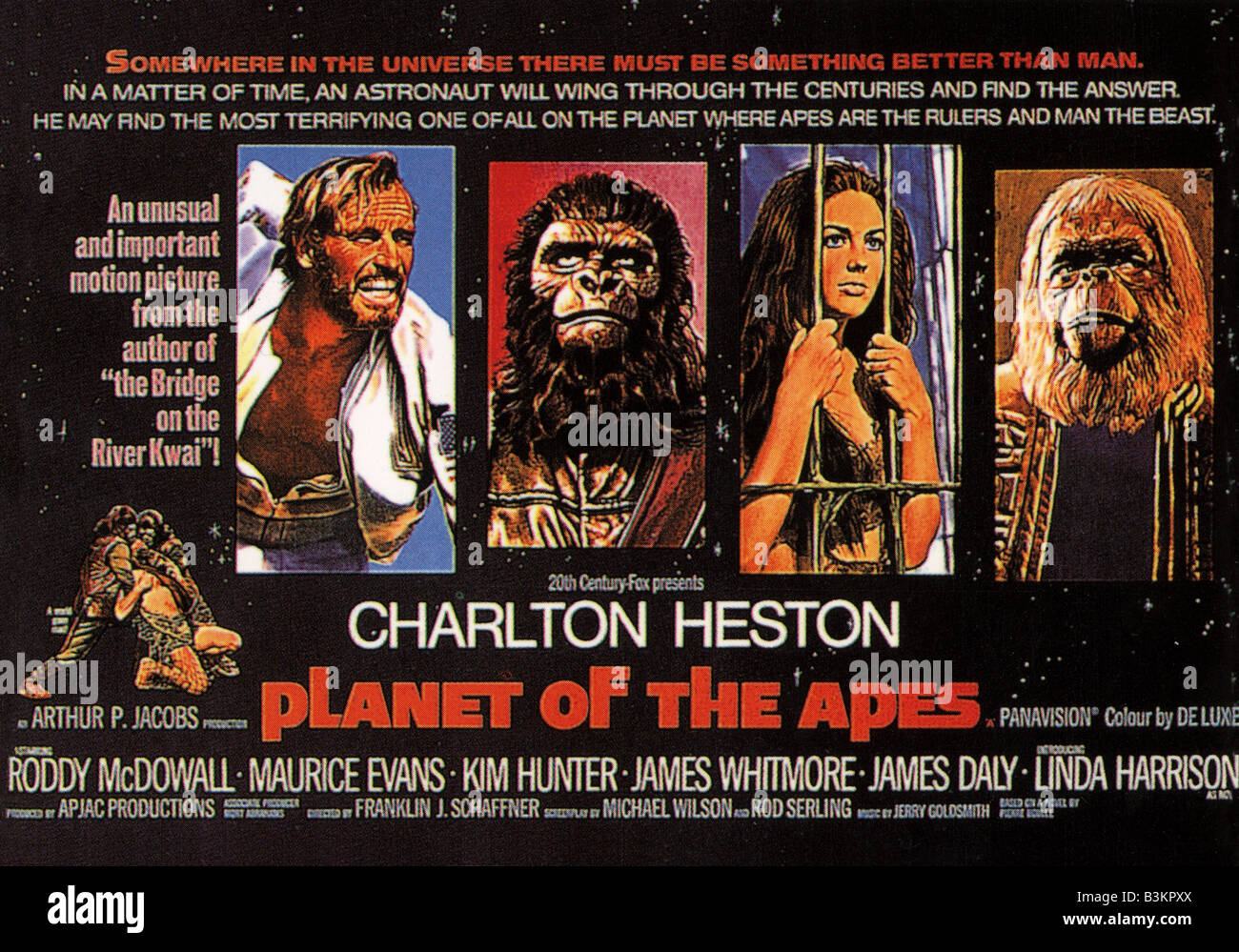

Charlton Heston didn't just play Taylor; he growled him into existence. You’ve got this cynical, misanthropic astronaut who hates humanity enough to blast off into deep space, only to find himself caged by a civilization that treats humans like vermin. The irony isn't just heavy-handed—it's the whole point.

What Most People Forget About the Planet of the Apes 1968 Movie

The production was a nightmare. Pure chaos. Originally, the script was supposed to mirror a high-tech city, much closer to Pierre Boulle’s 1963 novel La Planète des singes. But money talks. The studio, 20th Century Fox, was terrified of the budget. They’d just been burned by the massive cost of Cleopatra, so they told the producers to dial it back. That’s why we got the primitive, mud-brick architecture of Ape City. Honestly? It was a blessing in disguise. It made the world feel ancient, grounded, and way more unsettling than a bunch of futuristic skyscrapers would have.

Rod Serling, the mastermind behind The Twilight Zone, wrote the first few drafts. You can feel his fingerprints all over the final product, even though Michael Wilson came in later to sharpen the dialogue and lean into the political subtext. Wilson was a blacklisted writer during the McCarthy era, which explains why the trial scenes feel so personal and stinging. He knew what it was like to be persecuted by a "sacred" establishment.

The Make-up Revolution

John Chambers. That’s the name you need to know. Before this film, prosthetic makeup was basically just masks that didn't move. You couldn't see the actor's eyes or their expressions. Chambers spent months studying apes at the Los Angeles Zoo, trying to figure out how to translate their anatomy onto human faces without losing the performance.

He won an honorary Oscar for it because, at the time, there wasn't even a category for makeup. Think about that. The industry had to literally invent a way to recognize what he’d done. The actors—Kim Hunter as Zira and Roddy McDowall as Cornelius—had to stay in those appliances for hours, eating through straws and barely being able to rest. It sounds miserable. But the result? Those characters feel alive. When Zira smirks, you see it. When Dr. Zaius looks at Taylor with that mixture of pity and hatred, you feel it.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The Script That Almost Didn't Happen

Hollywood is built on "no." Everyone thought the Planet of the Apes 1968 movie would be a joke. They thought people would laugh at the screen. To prove it could work, producer Arthur P. Jacobs spent his own money to film a screen test. He grabbed Heston and Edward G. Robinson (who was originally supposed to play Zaius) and put them in some early-concept makeup. It worked. Fox saw the footage and finally blinked.

Why the Science-Fiction Matters

Science fiction is often just a mirror. In 1968, America was tearing itself apart. The Vietnam War was raging, the Civil Rights Movement was at a boiling point, and the Cold War was a constant, low-frequency hum of anxiety.

Then comes this movie.

It talks about class. It talks about race. It talks about the "Church vs. Science" debate in a way that’s still uncomfortably relevant. Dr. Zaius isn't just a villain; he’s a Minister of Science who is also the Defender of the Faith. He’s a gatekeeper. He knows the truth about the past, but he buries it to "protect" his society. That’s some heavy stuff for a movie people thought was just about talking monkeys.

The hierarchy of the apes themselves was a blatant swipe at human prejudice:

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

- Gorillas: The military and muscle.

- Orangutans: The politicians and religious leaders.

- Chimpanzees: The intellectuals and scientists.

It’s a rigid, stagnant system. Taylor, with his "stinking paws" and his refusal to shut up, is the ultimate disruptor. He’s the ghost of a dead world coming back to haunt the new one.

That Ending (The Reveal Heard 'Round the World)

We have to talk about the Statue of Liberty. It’s arguably the most famous twist in cinema history. If you somehow haven't seen it, first of all, how? Second of all, it changes everything.

Throughout the movie, Taylor thinks he’s on another planet. He thinks he’s light-years away from the "idiots" he left behind. When he finds that charred, half-buried torch in the sand, the realization isn't just that he’s on Earth—it’s that humanity finally did it. We pushed the button. We nuked ourselves into oblivion.

Heston’s delivery of "You maniacs! You blew it up! Ah, damn you! God damn you all to hell!" wasn't even in the book. In the novel, the twist is different—Taylor gets back to Earth only to find that apes have taken over there, too. But the movie’s version? It’s far more nihilistic. It’s a gut-punch that leaves the audience complicit.

Technical Mastery Under Pressure

Director Franklin J. Schaffner used a lot of handheld camera work and wide-angle lenses to make the Forbidden Zone feel desolate and massive. They filmed in Glen Canyon, Utah, and around Lake Powell. The landscape is alien because it’s so stark. There’s no CGI to hide behind. It’s just sun, rock, and sweat.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The score by Jerry Goldsmith is another reason this movie stays with you. It’s avant-garde. He used echoplexes, Brazilian instruments, and even had the horn players remove their mouthpieces to create these jarring, percussive sounds. It doesn't sound like a "movie score." It sounds like a world that has forgotten what music is supposed to be.

How the Planet of the Apes 1968 Movie Changed the Business

Before this, movie franchises weren't really a thing, at least not in the way we see them now. Sure, you had James Bond, but Apes created a template for merchandising and sequels. It spawned four sequels, two TV shows, and eventually the massive reboot trilogy in the 2010s.

It proved that "high-concept" sci-fi could be a summer blockbuster. It showed that audiences were willing to engage with dark, unhappy endings if the journey was worth it.

Common Misconceptions

- "The apes are the bad guys." Not really. They’re just us. They’ve inherited our flaws, our bureaucracy, and our fear of the unknown.

- "It’s a kids' movie." No. It’s incredibly violent in its implications and bleak in its philosophy.

- "The makeup looks dated." Compared to $200 million CGI? Maybe. But there is a tactile, physical presence to those 1968 prosthetics that digital effects often struggle to replicate.

Taking a Closer Look Today

If you’re planning to revisit the Planet of the Apes 1968 movie, pay attention to the silence. Modern movies are terrified of a quiet moment. Schaffner lets the desert breathe. He lets the confusion on Taylor’s face linger.

Also, watch Dr. Zaius. He’s the most complex character in the film. He isn't evil for the sake of being evil. He’s a man (or an ape) who believes that human nature is fundamentally destructive. Looking at the state of the world Taylor left behind, can you really tell Zaius he’s wrong?

Practical Insights for Fans and Cinephiles

- Watch the documentaries: If you can find the Behind the Planet of the Apes documentary narrated by Roddy McDowall, watch it. The footage of the actors eating lunch in full makeup is surreal.

- Compare to the novel: It’s worth reading Pierre Boulle’s book just to see how much the film deviated. The movie is much more of a "Western" in its pacing and tone.

- Look for the subtext: Notice how the trial of Taylor mirrors the Scopes Monkey Trial. It’s a deliberate nod to the history of anti-evolution sentiment in America.

The Planet of the Apes 1968 movie isn't just a relic of the past. It’s a warning. It’s a masterclass in production design. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most alien thing we can encounter is our own reflection in the mirror.

To get the full experience of the franchise's evolution, start by watching the 1968 original alongside the 2011 Rise of the Planet of the Apes. The thematic bridge between the two—the hubris of man and the inevitable rise of a new power—is one of the most consistent and fascinating arcs in all of cinema. Pay close attention to the use of "No!" in both films; it’s the spark of revolution in 1968 and 2011 alike, marking the exact moment the power dynamic shifts forever.