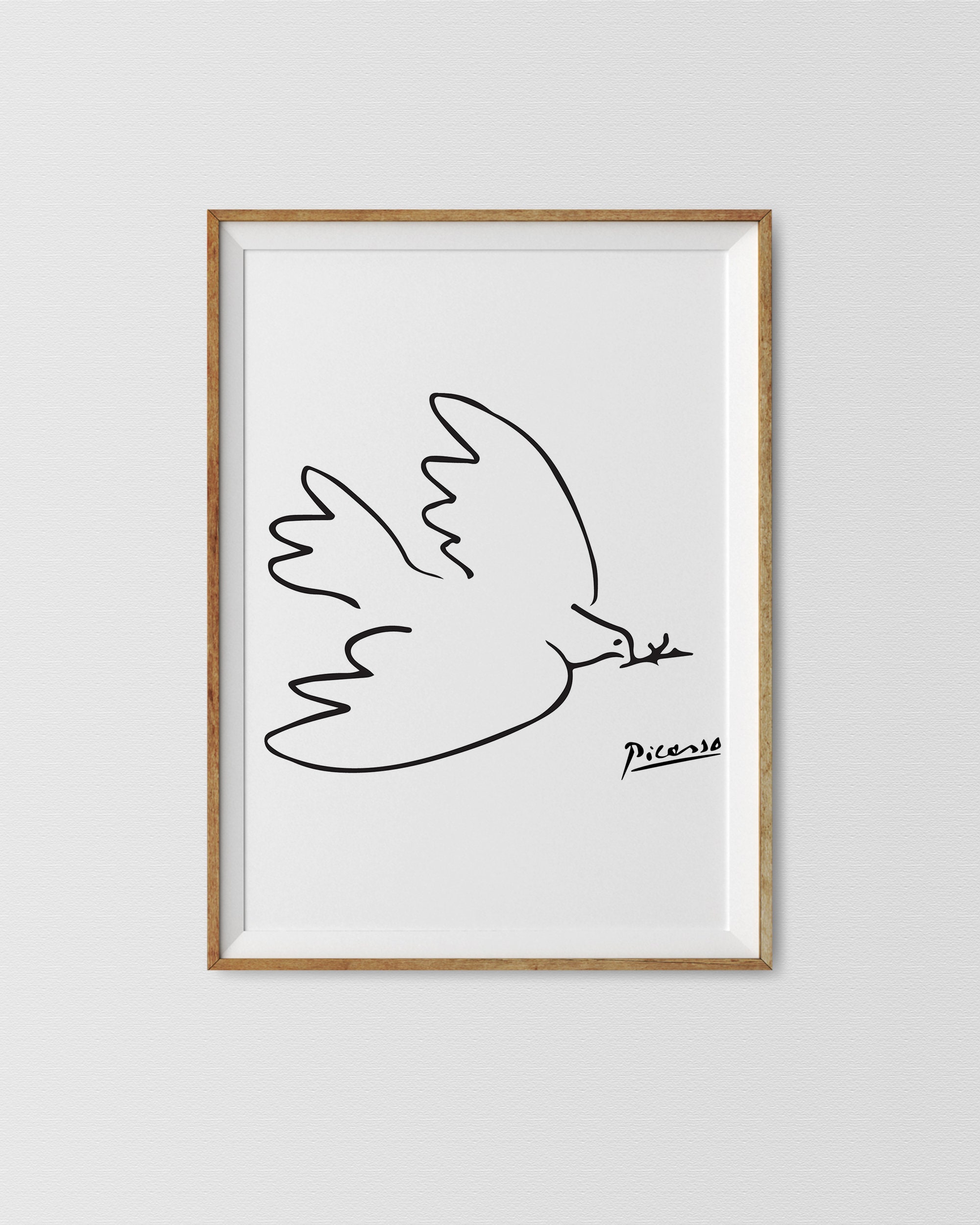

It’s just a bird. Seriously, if you look at it without the weight of art history or the political chaos of the mid-20th century, the Picasso dove of peace original is a surprisingly simple lithograph. It’s white. It’s fluffy. It looks like something you might see in a high-end nursery or a minimalist café. But that little bird carries more political baggage and historical grit than almost any other doodle in history.

Pablo Picasso didn't just wake up one day and decide to become the poster boy for global pacifism. It was 1949. Europe was still smoldering from World War II. The Cold War was freezing over. The Communist-backed World Peace Congress needed a symbol, and they needed something that didn't look like a tank or a fist. They went to Picasso’s studio on the Rue des Grands-Augustins in Paris.

Louis Aragon, a poet and friend of Picasso, was the one who sifted through the artist’s folders. He found a lithograph of a pigeon. Not a majestic, mythical dove—a pigeon. Specifically, it was a Milanese pigeon with feathered legs, a gift from his rival and friend Henri Matisse.

Picasso was skeptical. He actually joked about it later, noting that pigeons are notoriously aggressive birds. "I have some here," he supposedly said, "and they don't give each other any peace at all." Yet, that "pigeon" became the Dove.

The Story Behind the Picasso Dove of Peace Original

Most people assume Picasso just drew a quick sketch for a poster. That’s not quite it. The Picasso dove of peace original from 1949 was a highly technical lithograph. If you look at the first version—the one used for the Paris Peace Congress—it’s actually quite realistic. It has soft grey tones, detailed feathers, and a solid sense of weight. It wasn't the "one-line" drawing we see on t-shirts today.

The choice of a bird was deeply personal. Picasso’s father, José Ruiz y Blasco, was a painter who specialized in birds, specifically pigeons and lilacs. Pablo grew up around them. When he was a kid, he’d finish his father’s paintings by adding the legs. By choosing a dove, he was reaching back into his own childhood while simultaneously handing the world a symbol of hope.

It’s also worth mentioning that Picasso was a member of the French Communist Party at the time. This gave the image a sharp political edge. In the West, some saw it as "Red" propaganda. In the East, it was a badge of honor. It’s wild to think that a simple lithograph of a bird could be a lightning rod for FBI surveillance and Soviet accolades at the same time.

The image evolved. Over the next few years, Picasso stripped it down. He moved away from the realistic, shaded bird of 1949 and toward the iconic, minimalist line drawings. He’d draw them on napkins, on posters, in the dirt. He realized that the simpler the line, the easier it was to replicate. It became the first truly viral image of the modern age.

Why Is It a Dove and Not a Pigeon?

Biologically, they’re basically the same thing. But symbolically? Huge difference. The dove has biblical roots—Noah, the olive branch, the end of the flood. Picasso knew exactly what he was doing by leaning into that iconography, even if his actual model was a "pigeon" from Matisse's coop.

Spotting a Real Original vs. a Modern Print

If you're looking for a Picasso dove of peace original, you need to know what you're actually hunting for. There isn't just "one" original. There’s the first stone lithograph, and then there are the subsequent variations he did for peace congresses in Wroclaw, Sheffield, and Vienna.

- Check the Paper: True mid-century lithographs were often printed on Arches or Rives BFK paper. If it feels like modern, bright-white laser paper, it’s a reproduction.

- The Signature: Picasso signed a lot of things. But he also had "estate stamps" applied after his death. A hand-signed pencil signature is the gold standard, but be careful—Picasso's signature is one of the most forged in the world.

- The Edition Number: Look for a fraction like 25/50. This tells you it was the 25th print in a run of 50. If there’s no number, it might be an "Artist’s Proof" (marked AP or EA), or it might just be a mass-produced poster from the 80s.

Honestly, most of what you see in vintage shops or on eBay are later reprints. The 1949 lithograph is rare. It’s held in major institutions like the Tate in London or the MoMA in New York. If someone is selling an "original" for $200, they’re lying to you. Or they have no idea what they have.

The Evolution of the Line

Picasso’s later doves, like the 1961 "Dove of Peace" with the olive branch, are masters of "less is more."

🔗 Read more: Black Safety Shoes Mens: What Most People Get Wrong About Choosing Duty Footwear

Think about it. He could have painted a massive, complex mural like Guernica every time he wanted to talk about war. Instead, he chose a single, unbroken line. It was a flex. He was showing that he could capture the soul of a movement with a flick of his wrist. It was also practical. Anyone could draw a version of it on a protest sign. It belonged to the people, not just the galleries.

The Political Backlash Nobody Talks About

We see the dove as "tame" now. Back then? It was controversial. During the 1950s, the U.S. government was incredibly suspicious of Picasso. He was a high-profile Communist supporter. The dove was seen by some as a "Trojan Horse"—a way to make the Soviet-backed peace movement look soft and fuzzy while the Cold War escalated.

There’s a famous story about the 1950 Sheffield Peace Congress. The British government actually refused visas to many of the delegates. Picasso managed to get in, but he was followed. When he got up to speak, he didn't give a long political manifesto. He just talked about his father teaching him to draw birds. He humanized the symbol so effectively that the political critics looked silly.

It’s kind of funny, really. The bird was so successful that it eventually lost its specific "Communist" ties and just became the universal sign for "Please stop shooting each other." Picasso won that round.

How to Value and Collect Picasso Lithographs

If you are serious about art as an investment, the Picasso dove of peace original lithographs are tricky. The market is flooded with "After Picasso" prints. These are prints made by others, based on his designs, often with his permission but not his physical touch.

- Hand-signed lithographs: These can fetch anywhere from $5,000 to $50,000 depending on the specific edition and condition.

- Unsigned limited editions: These are still valuable, often in the $1,000 to $5,000 range.

- Vintage posters: Posters printed during Picasso's lifetime for specific exhibitions are highly collectible. They might not be "fine art" in the strictest sense, but they have immense historical value.

Condition is everything. Foxing (those little brown spots on old paper), sun fading, and "mat burn" from cheap frames can kill the value of an original. If you find one, don't touch it with your bare hands. The oils from your skin will mess with the paper over time.

The Matisse Connection

You can't talk about the dove without Matisse. The two giants of 20th-century art were competitive but had deep respect for each other. When Matisse was dying, he gave Picasso some of his cherished pigeons. By using one of those birds as the basis for the peace symbol, Picasso was also creating a tribute to his friend. It’s a layer of the story that most people miss—the dove isn't just about global politics; it's about a personal friendship between two old men who had seen the world break apart twice.

What to Do If You Want to Own One

Don't just go to an online auction site and hope for the best. You'll get burned.

First, educate yourself on the "Catalogue Raisonné." For Picasso’s prints, the bible is the Fernand Mourlot catalog. Mourlot was Picasso’s master printer. If a print isn't listed in "Mourlot," it’s probably not an original.

Second, buy from reputable dealers who offer a "Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity." Not a "Certificate of Authenticity" (COA) printed from a home computer, but a legal guarantee from a member of the International Fine Print Dealers Association (IFPDA).

📖 Related: July 4th Nail Designs: Why Most People Settle for Basic Stripes (and What to Do Instead)

Finally, think about why you want it. If it’s just for the "look," buy a high-quality giclée print for $50 and spend the rest of your money on a vacation. But if you want a piece of history—a physical link to the moment art tried to stop a war—then the hunt for an original is worth it.

The Picasso dove of peace original isn't just an image. It's a reminder that even in the middle of a cold, hard world, something as fragile as a bird can carry a lot of weight. Picasso didn't just draw a bird; he gave a voice to a feeling that most people were too tired or too scared to put into words.

Actionable Steps for Art Enthusiasts

- Visit a Major Collection: Before buying, see the real thing. The MoMA in New York and the Musée Picasso in Paris have excellent examples of his lithographic work. Notice the texture of the ink and the way it sits on the paper.

- Study the Mourlot Catalog: Familiarize yourself with the various "states" of the dove. Picasso often changed the image between printing runs, and these variations matter to collectors.

- Consult an Appraiser: If you think you've found an original in an estate sale or attic, don't frame it yet. Take it to a professional art appraiser who specializes in 20th-century prints.

- Invest in Conservation Framing: If you do acquire an original, use UV-protective glass and acid-free mounting. Sunlight is the enemy of 1940s paper.

The market for Picasso remains one of the most stable in the art world. While styles come and go, the demand for his most iconic symbols—the dove being the primary one—tends to stay high. It’s a foundational piece of visual culture. Understanding the difference between the mass-produced icon and the hand-pulled lithograph is the first step in becoming a serious student of his work.