If you walk down Malet Place in Bloomsbury, past the bustling students of University College London, you might miss it. There’s a nondescript door. Behind it lies one of the most concentrated collections of Egyptian and Sudanese archaeology on the planet. Honestly, if you’re expecting the echoing marble halls and gold-leafed grandeur of the British Museum, you’re in for a shock. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology is different. It’s crowded. It’s cramped. It’s basically a library of objects where the shelves groan under the weight of 80,000 artifacts. This isn't a place for casual tourists looking for a quick photo of a mummy. It’s for people who want to touch the grit of the ancient world.

William Matthew Flinders Petrie was a bit of a character. People called him the "Father of Scientific Archaeology," which sounds prestigious, but he was also the kind of guy who supposedly worked in his pink underwear to keep cool in the desert heat. He didn't care about the shiny gold stuff that tomb robbers and early "explorers" obsessed over. Petrie cared about the mundane. He looked at broken pottery and thought, "This is a timeline." He was obsessed with the everyday lives of ordinary people. Because of that obsession, the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology houses things you won't see anywhere else—like the world’s oldest dress or the first ever example of blue glazing.

What You’re Actually Seeing at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

Most museums curate. They pick the "best" five things and hide the other five hundred in a basement. The Petrie doesn't really do that. It’s a teaching collection. This means the cases are packed. You’ll see rows of beads, stacks of pottery, and hundreds of tiny figurines called shabtis. It can feel overwhelming at first. Just breathe.

The Tarkhan Dress is the undisputed star here. It’s a linen shirt, essentially, with beautifully pleated sleeves, dating back to the First Dynasty—around 3000 BC. Think about that for a second. This garment was worn by someone five millennia ago. It survived because the dry Egyptian sand preserved the fibers, and it was eventually rediscovered in a pile of linen rags that Petrie excavated in 1913. It wasn't even identified as a dress until 1977 when conservationists at the Victoria and Albert Museum took a closer look. It’s fragile. It’s grey. It’s incredibly human.

The Science of Seeing

Petrie revolutionized how we understand time. Before him, archaeology was basically treasure hunting. He developed "sequence dating," a method of looking at the evolution of pottery styles to create a chronological framework. If you look at the pottery displays in the museum, you’re looking at the birth of modern archaeological science. It’s not just "old pots." It’s a map of human progress.

✨ Don't miss: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

Then there are the Roman-era mummy portraits. These aren't the stylized, stiff faces you see on wooden sarcophagi from the New Kingdom. These are Hawara portraits—painted in encaustic (wax) on wood. They look like people you’d meet on the street today. The eyes are soulful. The hair is styled in the Roman fashion. They remind you that the people who lived in the Faiyum Oasis two thousand years ago were individuals with egos, families, and a desperate desire to be remembered as they truly appeared.

Why Small Museums Beat the Giants

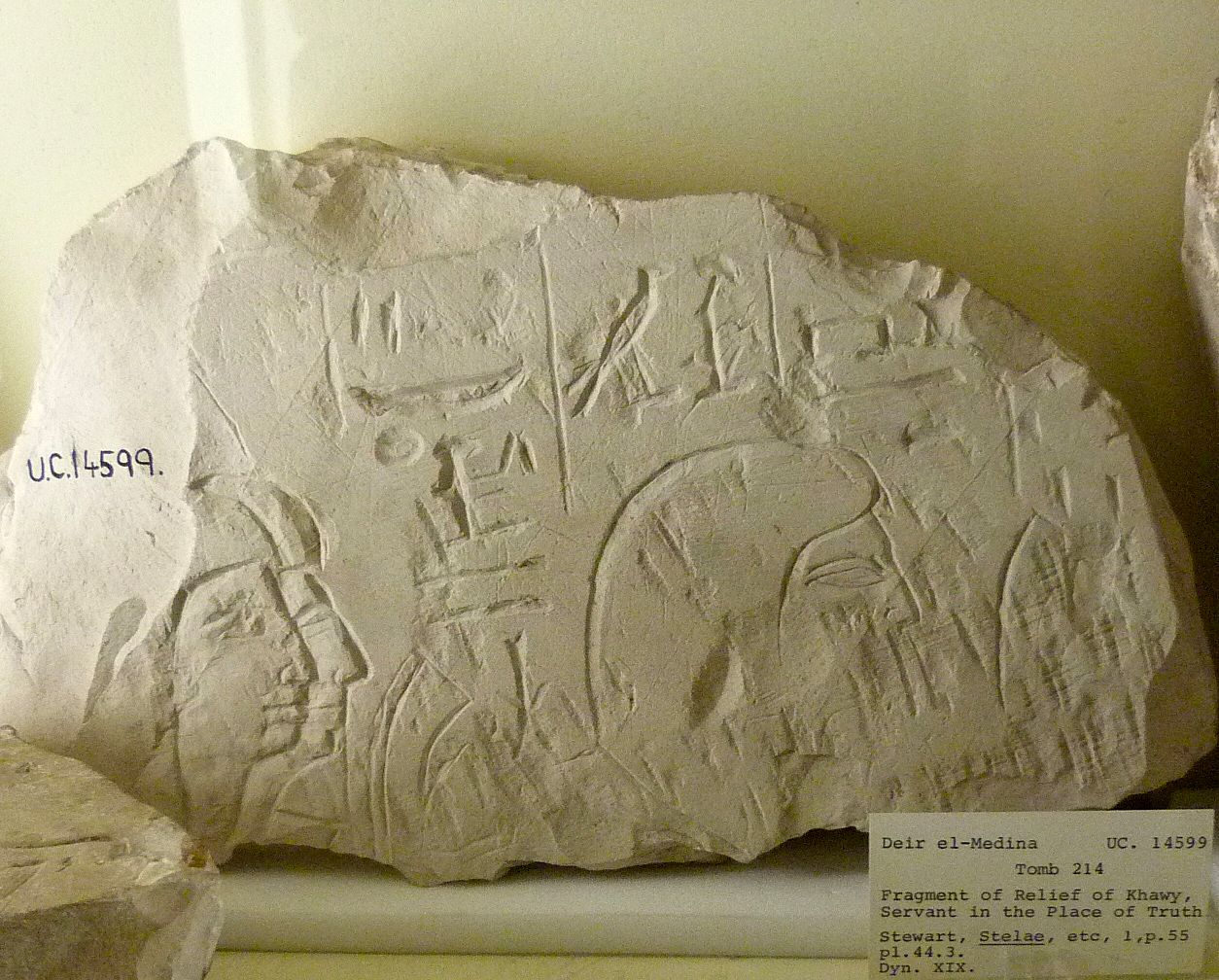

Size isn't everything. Big museums have crowds that make it impossible to actually see the art. At the Petrie, you can stand three inches away from a 4,000-year-old limestone relief and notice the chisel marks. You can see the thumbprints of a potter in a bowl from the Predynastic period. It’s intimate.

- The Lack of Pretense: There are no velvet ropes here. You’re in a room full of wooden cabinets that look like they belong in an old pharmacy.

- The Focus on the "Normal": While the British Museum has the Rosetta Stone, the Petrie has the tools used to build the pyramids. It has ancient makeup pots, hair combs, and even a set of prehistoric "marbles" (gaming pieces).

- The Connection to UCL: Because it’s part of the university, the atmosphere is academic but accessible. You’ll often see students sketching or researchers peering into cases.

The collection was founded in 1892 when Amelia Edwards, a prolific writer and traveler, donated her collection and funded a chair of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at UCL. She was a powerhouse. She traveled up the Nile in a dahabeah and came back convinced that Egypt’s heritage was being destroyed by looting. She wanted a place where the science of Egyptology could flourish. Petrie was the first professor. He brought back the fruits of his annual excavations, often funded by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt.

The Reality of the "Dusty" Aesthetic

Let’s be real: some people find the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology a bit much. It’s a "visible storage" museum. This means the lighting can be dim to protect the textiles, and the labels are sometimes hand-written or typed on old-school typewriters. It’s a vibe. If you like the feeling of being an explorer in an attic, you’ll love it. If you need interactive touchscreens and 4K projections, you might be disappointed.

🔗 Read more: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

But there’s magic in that dust.

Take the Amarna collection, for example. This was the city built by the "heretic" Pharaoh Akhenaten. The art from this period is weird. It’s fluid and organic, a total departure from the rigid lines of traditional Egyptian art. The Petrie has fragments of colorful glass and glazed tiles from Akhenaten’s palace. The colors are still vibrant—cobalt blues and deep reds that look like they were fired yesterday. It’s a glimpse into a revolutionary moment in history that crashed and burned within twenty years.

Acknowledging the Elephant in the Room

We have to talk about provenance. In the 21st century, the ethics of colonial-era collecting are under a microscope. The Petrie Museum is quite transparent about this. They work closely with Egyptian colleagues and are part of the ongoing global conversation about how these objects should be managed and where they belong. Much of Petrie’s work was done under a system called partage, where the find was split between the country of origin and the excavator's home institution. It was the standard of the time, but standards change. The museum today serves as a hub for research that often benefits Egyptian archaeology directly, providing a digital archive that scholars worldwide can access.

Practical Advice for Your Visit

You can’t just turn up and expect a gift shop the size of a department store. It’s a small operation.

💡 You might also like: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

- Check the Opening Hours: They are often limited, usually opening in the afternoons from Tuesday to Saturday. Always check the UCL website before you trek across London.

- Find the Entrance: It’s in the Malet Place alleyway. Look for the signs for the "DMS Watson Building." It’s a bit of a maze.

- Start with the Textiles: Since they have some of the rarest ancient cloth in the world, head to the back where the climate-controlled cases are.

- Look Down: Some of the best stuff is in the lower drawers of the cabinets. You’re allowed to look through the glass, obviously, but don't try to open them!

- Combine it with the Grant Museum: If you’re into slightly macabre or old-school science, the Grant Museum of Zoology is just a short walk away. It’s full of skeletons and jars of specimens.

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology isn't just a museum; it's a testament to a specific way of looking at the world. It’s about the value of the fragment. A tiny scrap of papyrus with a tax receipt on it tells us more about the Roman administration of Egypt than a giant statue of an anonymous god ever could. It’s about the people who lived, breathed, paid taxes, and wore pleated dresses.

How to Support the Collection

The museum is free. That’s a miracle in a city as expensive as London. They rely on donations and university funding to keep the lights on and the conservators working. If you visit, consider buying a book from their small desk or leaving a few pounds in the donation box. Every bit helps preserve the Tarkhan Dress for another hundred years.

When you leave, you’ll likely feel a bit dazed. The transition from the 12th Dynasty to the noise of Gower Street is jarring. But you’ll carry that sense of connection with you. You’ve seen the hairpins of a woman who lived 4,000 years ago. You’ve seen the toys of children who played in the mud of the Nile. That’s the real power of the Petrie. It collapses time. It makes the "ancient" feel remarkably present.

To make the most of your trip to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, start by browsing their online catalog. They have digitized a massive portion of the collection, and knowing the story behind a few specific objects—like the "Heh" amulets or the Maya and Merit reliefs—will make the physical experience much richer. Once you're there, don't try to see everything. Pick one row of cases and really look at the labels. Notice the materials: carnelian, lapis lazuli, faience. Think about the trade routes required to get those stones to the Nile Valley. This museum rewards the slow observer, the person willing to squint at a tiny scarab and wonder whose hand it rested in three millennia ago.