Food is messy. We like to think we understand what’s on our plate because we read the back of a Cheerios box or track "macros" on an app, but honestly? We’re mostly guessing. We know about protein, fats, carbs, and maybe a handful of vitamins. That’s about 150 components. In reality, a single onion contains thousands of distinct chemical compounds. We've been looking at the nutritional world through a keyhole, and the Periodic Table of Food Initiative (PTFI) is basically trying to kick the door down.

It’s an ambitious, slightly crazy, and deeply necessary global project.

The goal isn't just to make a pretty poster for high school chemistry labs. It’s about mapping the "dark matter" of nutrition. Right now, most of the world relies on food composition databases that are, frankly, ancient. Some entries haven't been updated in decades. They focus on the big stuff—calories and basic minerals—while ignoring the complex biomolecules that actually dictate how our bodies fight inflammation or repair DNA.

What the Periodic Table of Food Initiative Is Really Doing

Think about a carrot. Depending on whether that carrot grew in the regenerative soil of a boutique farm in Vermont or the depleted dirt of a massive industrial plot in the Central Valley, its chemical makeup is wildly different. One might be packed with falcarindiol (a compound linked to heart health), while the other is mostly water and sugar. The PTFI is standardizing how we measure this stuff.

They aren't just looking at "food." They are looking at everything in the food.

By using advanced mass spectrometry and high-resolution analytics, the initiative is cataloging the biomolecular fingerprints of the world's most important food crops. We're talking about over 1,000 different foods. This isn't just a Western project, either. One of the coolest things about the PTFI is its focus on "underutilized" or "orphan" crops. Things like bambara groundnut or teff. These are crops that are vital for food security in the Global South but have been ignored by Big Ag because they aren't as profitable as corn or soy.

Why standardizing the data matters so much

If you’re a researcher in Ethiopia and I’m a researcher in Tokyo, we need to speak the same language. Before this, everyone used different methods to measure nutrients. It was a mess. The PTFI created a standardized "kit" and cloud-based platform so that labs across the globe can contribute data that actually matches up.

It’s democratizing food science.

🔗 Read more: Images of the Mitochondria: Why Most Diagrams are Kinda Wrong

Dr. Selena Ahmed, the Executive Director of the PTFI, often talks about how this data can bridge the gap between agriculture and medicine. We’ve treated them as separate fields for too long. Farmers grow for yield; doctors treat for symptoms. The periodic table of food approach forces us to realize that the quality of the soil literally dictates the medicine in our food.

The "Dark Matter" of Your Lunch

Scientists often refer to the thousands of unmapped compounds in food as "nutritional dark matter." It sounds like something out of a Marvel movie, but it's just the stuff we haven't bothered to name or track yet.

Consider polyphenols.

We know they’re "good." But which ones? In what concentrations? How do they interact with your specific gut microbiome? The PTFI is providing the raw data so we can finally answer those questions. They are moving us away from the "one-size-fits-all" RDA (Recommended Dietary Allowance) and toward a world where we understand that a specific heirloom variety of corn might have 10 times the antioxidant capacity of the standard yellow dent corn.

Misconceptions About the Project

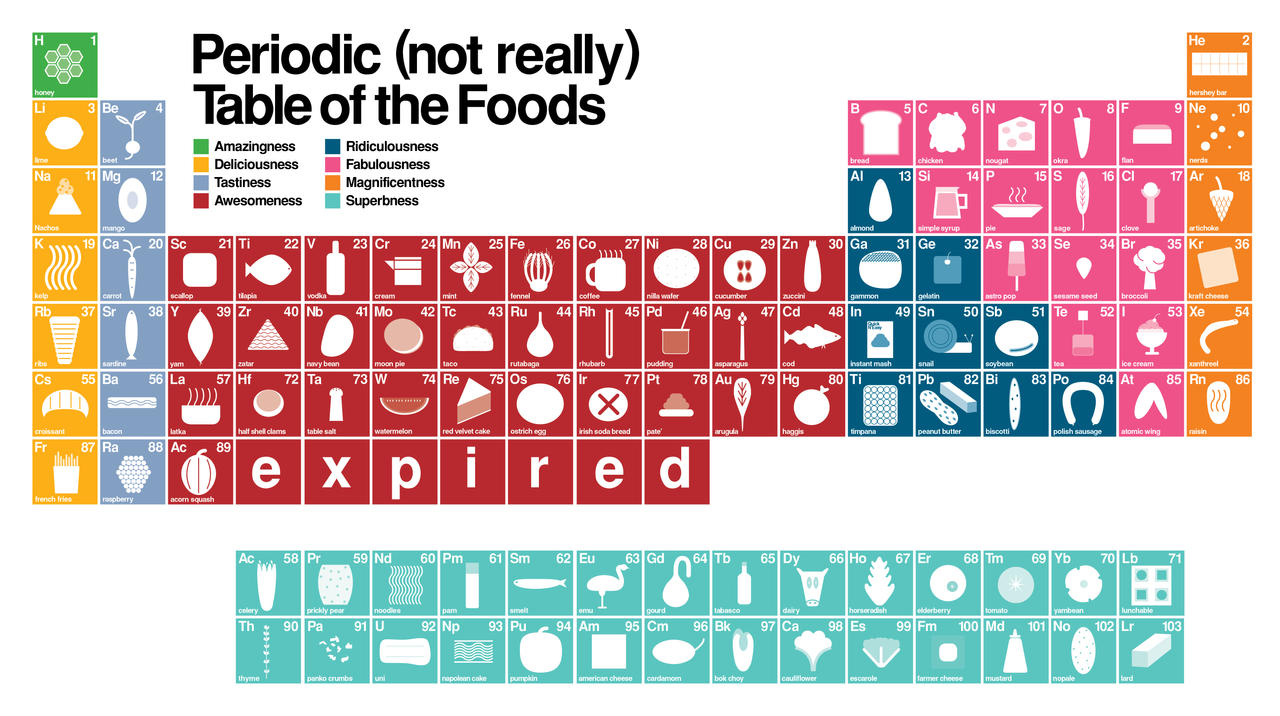

People hear "Periodic Table of Food" and they expect a literal table with 118 elements. That’s not what this is.

It’s more of a massive, searchable, multidimensional database.

It’s also not a way for big tech to "disrupt" food by making everything synthetic. If anything, it’s the opposite. By highlighting the incredible complexity of whole foods, the PTFI makes a very strong case for biodiversity. It shows that we can’t just "fortify" our way out of a bad diet. You can’t just add three vitamins to a highly processed cracker and call it health food when you’re missing the 400 other compounds that were in the original grain.

💡 You might also like: How to Hit Rear Delts with Dumbbells: Why Your Back Is Stealing the Gains

It’s about climate change, too

Plants are stressed. When a plant deals with drought or pests, it produces secondary metabolites—essentially its own internal defense system. These are often the very compounds that are healthiest for humans. As the climate shifts, the chemical profile of our food is shifting. The PTFI allows us to track these changes in real-time. We can see which varieties of crops are staying nutrient-dense under heat stress. That is huge for the future of how we survive on this planet.

How This Actually Affects You

You might think, "Okay, cool science, but I just want to know what to eat for dinner."

Fair point.

The trickle-down effect of the periodic table of food will eventually hit your grocery store. Imagine a future where a QR code on a bunch of kale tells you not just the calories, but the specific nutrient density compared to the average. Or a future where a doctor prescribes a specific variety of bean because it’s high in a compound your body specifically needs to manage inflammation.

We’re moving from "food as fuel" to "food as information."

It’s also going to change how food is labeled. The current "Nutrition Facts" label is a relic of the 1990s. It’s boring and incomplete. Once the PTFI data becomes the global standard, expect those labels to get a lot more interesting—or at least more accurate regarding what’s actually inside the package.

The Real Power Players Behind the Initiative

This isn't just a group of hobbyists. The PTFI is a massive collaboration. You've got the American Heart Association, the Alliance of Bioversity International, and CIAT. It’s supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. These are heavy hitters. They are working with the Verso Computing Platform to handle the insane amount of data they’re generating.

📖 Related: How to get over a sore throat fast: What actually works when your neck feels like glass

When you have this much institutional weight, things actually move. They are setting up Regional Centers of Excellence everywhere—from the University of Adelaide in Australia to the University of Ghana.

Where the Project Hits a Wall

Honestly, it’s not all sunshine and perfect data. There are massive challenges here.

- Cost: High-resolution mass spectrometry is expensive. Not every lab can afford the gear, even with a standardized kit.

- Complexity: Analyzing a single apple is exponentially harder than analyzing a piece of steel. Biological samples are "dirty" and vary by the hour.

- Big Food: Will the massive corporations that profit from nutrient-poor, ultra-processed foods actually want this transparency? Probably not. There’s going to be pushback when the data shows that certain "healthy" products are basically chemical deserts.

But even with those hurdles, the momentum is there. You can't un-know the truth once the data is public.

The Practical Shift: What to Do Now

You don't have to wait for the full database to be finished to use these insights. The core philosophy of the periodic table of food is that diversity is king.

Stop eating the same six things every week.

If you usually buy red apples, buy the weird, mottled green ones. If you always eat white rice, try black rice or fonio. The more you vary the species and varieties of plants you eat, the more likely you are to hit those "dark matter" nutrients that the PTFI is currently cataloging.

Actionable Steps for the Informed Eater

- Prioritize Heritage Varieties: Whenever you see "heirloom" or "heritage" at a farmer's market, grab it. These varieties often have a more complex chemical profile than their industrialized cousins.

- Focus on Soil Health: Look for brands or farmers that use regenerative practices. The PTFI is proving that soil health and nutrient density are inextricably linked.

- Diversify Your Grains: Most of us live on wheat, corn, and rice. Try ancient grains like millet, sorghum, or amaranth. These are exactly the types of "orphan crops" the PTFI is trying to bring back into the spotlight.

- Watch the Database: Keep an eye on the Periodic Table of Food Initiative website. They are rolling out data in phases. It’s an incredible resource for anyone who wants to see the actual science behind their meals.

The old way of looking at food—as a simple collection of fat, protein, and carbs—is dying. We’re entering an era where we can finally see the full picture. It’s about time we treated our food with the same scientific rigur as we treat our medicine. Because, at the end of the day, it's the same thing.

Stop thinking about your diet as a math equation and start thinking about it as a complex biological symphony. The more instruments (compounds) you have playing, the better the music sounds. This isn't just a trend; it's a fundamental shift in human understanding that will dictate how we grow, sell, and consume food for the next century. Get used to the idea that your dinner is a lot more complicated than you thought—and that's a very good thing.