Look at it. Really look at it. If you search for that famous picture of earth voyager 1 snapped back in 1990, you might actually miss the point entirely at first glance. It’s a grainy, pixelated mess. It looks like a mistake. There’s a brown band of light—scattered sunlight hitting the camera—and inside that beam, there is a tiny, microscopic speck.

That’s us. Everything.

Every war, every wedding, every tax return, and every sunset you’ve ever seen happened on that single pixel. It’s called the Pale Blue Dot, and honestly, it’s probably the most important photograph ever taken, even if it’s technically one of the lowest-quality images in the NASA archives.

The Picture NASA Almost Didn’t Take

You’d think a photo this iconic was a high-priority mission objective. It wasn’t. In fact, there was a lot of internal pushback at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) about even attempting the shot. Voyager 1 had already finished its primary mission. It had flown past Jupiter and Saturn. It was screaming away from the sun at about 40,000 miles per hour, heading into the dark.

Carl Sagan, who was part of the imaging team, had to beg.

He wanted the spacecraft to turn its camera around and look back at home one last time. Why? Because he knew the power of perspective. But engineers were worried. Pointing the sensitive cameras toward the Sun, even from nearly 4 billion miles away, could have fried the equipment. They didn't want to risk a perfectly good (albeit old) spacecraft for a "vanity" shot.

Eventually, Richard Truly, the NASA Administrator at the time, stepped in and gave the green light. On February 14, 1990, Voyager 1 turned its neck, clicked the shutter 60 times, and sent the data back to Earth. It took months for the signals to reach us and be processed. When the image finally appeared, it wasn't a crystal-clear marble. It was a smudge.

What You’re Actually Seeing in the Image

When you look at the picture of earth voyager sent back, the geometry of it is wild. The spacecraft was about 3.7 billion miles ($6 \times 10^9$ kilometers) away from us. To give you some scale, that’s about 40 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

📖 Related: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

The "beams" of light crossing the image aren't real structures in space. They are artifacts. Because the Sun was so close to Earth from Voyager's perspective, the light scattered inside the camera's optics. It just so happened that Earth was sitting right in the middle of one of those scattered rays.

It’s a lucky shot.

If Earth had been a fraction of a degree to the left or right, it might have been lost in the glare of the Sun entirely. The Earth in that photo is less than a single pixel in size—0.12 pixels, to be exact. It’s not even a full circle; it’s just a point of light caught in a dusty sunbeam.

The Technical Nightmare of 1990 Data

We take high-speed internet for granted now. But in 1990, getting that image back was a grueling process. The data was transmitted via the Deep Space Network. We’re talking about a bit rate that would make a 1990s dial-up modem look like fiber optics.

Each image was composed of 800,000 pixels. The "pale blue" color comes from the specific filters used. Voyager used a combination of green, blue, and violet filters to reconstruct the color. Because of the vast distance, the signal-to-noise ratio was incredibly low. It took hours of processing to separate the Earth from the background "noise" of the vacuum.

Why This Image Changed Science Communication Forever

Before this picture of earth voyager 1 took, space photography was about "The Other." We wanted to see the craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, or the Great Red Spot on Jupiter. We wanted to see what was out there.

Sagan flipped the script.

👉 See also: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

He realized that by looking back, we learned more about ourselves than we did about the solar system. It’s the ultimate ego-check. It reminds us that our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In his famous 1994 speech at Cornell University, Sagan noted that this photo underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another.

He wasn't just being poetic. He was being literal. From that distance, there are no borders. You can't see the Great Wall of China. You can't see the differences in skin color or religion. You just see a fragile, blueish light that could be snuffed out in a second by a rogue asteroid or our own stupidity.

The 2020 Remaster: Seeing the Speck More Clearly

For the 30th anniversary of the photo, NASA did something cool. They used modern image-processing techniques to "remaster" the original data.

Old-school 1990s computers had limits. They couldn't handle the subtle gradients of the scattered light very well. By using 21st-century software, JPL engineer Kevin Gill managed to clean up the image without "faking" any pixels.

The new version is stunning.

The "Pale Blue Dot" is still just a tiny speck, but the rays of sunlight are sharper, and the blackness of space looks deeper. It makes the Earth look even smaller, if that’s even possible. It reminds us that while our technology has improved drastically, our physical position in the universe remains just as precarious.

Misconceptions People Have About the Voyager Photos

People often confuse the Pale Blue Dot with the "Blue Marble."

✨ Don't miss: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

The Blue Marble was taken by the Apollo 17 crew in 1972. In that one, Earth looks huge and vibrant. You can see Africa and the Antarctic ice cap. It’s a "close-up" compared to the Voyager shot.

Another common mistake? Thinking this was the only photo Voyager took that day.

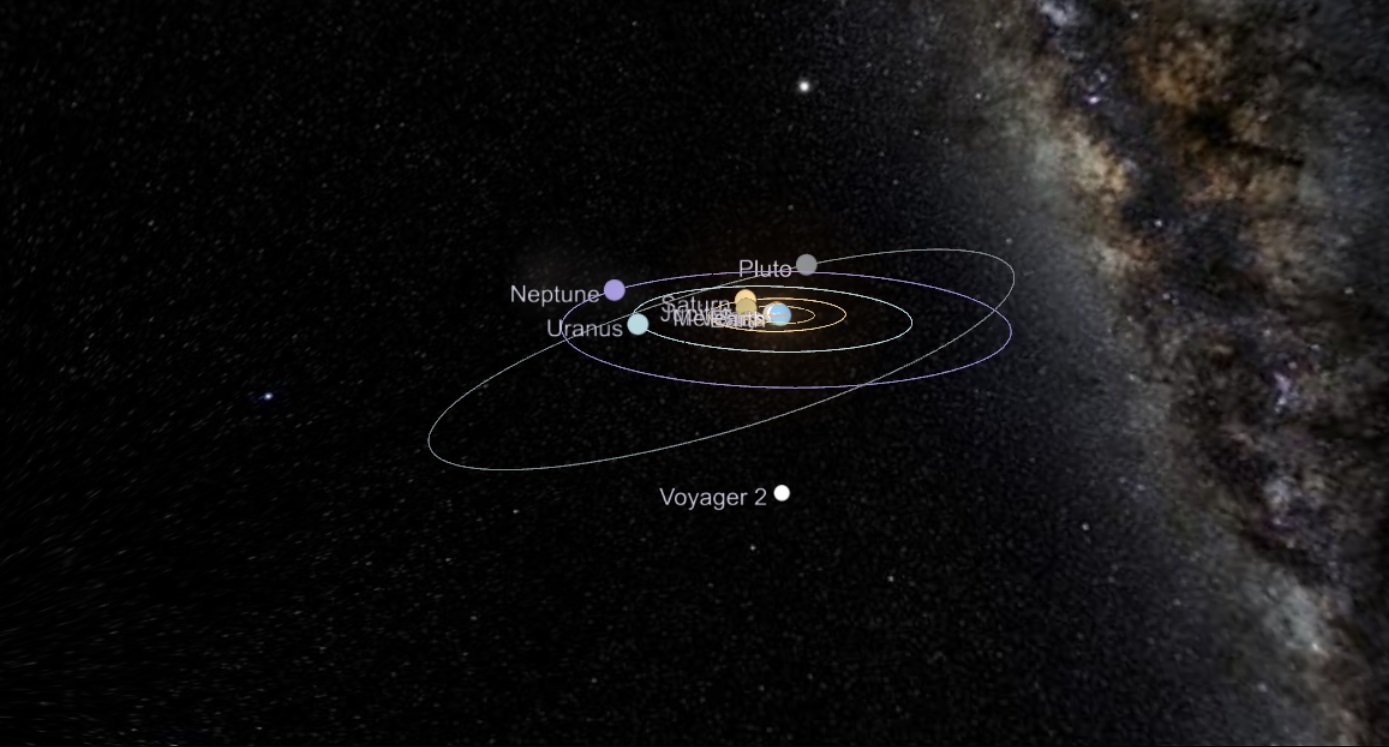

Actually, Voyager 1 took a whole "Family Portrait" of the solar system. It captured Neptune, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, and the Sun. It tried to get Mars and Mercury, but Mars was lost in the sun's glare, and Mercury was too close to the Sun to be seen at all.

Where is Voyager 1 Now?

As you read this, Voyager 1 is over 15 billion miles away from us. It has officially entered interstellar space—the space between the stars.

Its cameras are off.

NASA turned them off shortly after the picture of earth voyager 1 took was finished. They had to save power for the other instruments, like the ones measuring magnetic fields and plasma. The "eyes" of the craft are dead, but the craft itself is still "talking" to us, though its heartbeat is getting weaker every year.

By about 2030, we’ll likely lose contact forever. Voyager will become a ghost ship, drifting through the Milky Way for millions of years, carrying a golden record with our sounds and our stories. But for many, that one grainy photo is its greatest legacy.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you want to really connect with this piece of history, don't just look at a low-res thumbnail on your phone.

- Download the High-Res TIF: Go to the NASA JPL website and find the 2020 remastered version. Open it on a large monitor. Turn off the lights. Look at the Earth and try to find it without zooming in first. It changes how you feel about your Monday morning.

- Read the "Pale Blue Dot" Speech: Don't just read the snippets. Read Carl Sagan's full "Reflections on a Mote of Dust" passage. It is widely considered one of the greatest pieces of 20th-century literature.

- Track Voyager in Real Time: NASA has a "Mission Status" website that shows exactly how many miles away Voyager 1 and 2 are right now. Watching the "Distance from Earth" counter tick up at 10 miles per second is a sobering experience.

- Check the Family Portrait: Don't just look at Earth. Look at the full mosaic of the solar system Voyager captured. It provides the context of just how much empty space exists between us and our "neighbors."

This image isn't just "science." It’s a mirror. It’s a reminder that we are all on a very small boat in a very large ocean, and we’d better start acting like it.