Look at it. Seriously, look at it. If you zoom in enough on that grainy, 1990-era digital noise, you’ll find a speck. It’s smaller than a pixel. It’s a tiny, fragile-looking dust mote suspended in a sunbeam. That’s us. That is the picture of Earth from Voyager—specifically Voyager 1—and it remains, arguably, the most important photograph ever taken by a machine.

Most people think of space photos and imagine the high-definition, swirling nebulas of the James Webb Space Telescope or the vibrant, marble-like clarity of the 1972 "Blue Marble" shot from Apollo 17. Those are beautiful. They make Earth look like a lush, inviting jewel. But the Voyager image, known formally as the "Pale Blue Dot," does something else entirely. It makes us look insignificant. It’s humbling in a way that’s almost uncomfortable. Honestly, it’s a bit terrifying when you realize that everything we’ve ever known—every war, every love story, every boring Tuesday—happened on that microscopic dot.

The Fight to Turn the Camera Around

It almost didn't happen. By 1990, Voyager 1 had finished its primary mission. It had cruised past Jupiter and Saturn, snapping incredible shots of rings and moons. It was headed out of the solar system, moving at roughly 40,000 miles per hour toward the interstellar void. The mission was basically over. NASA was ready to shut down the cameras to save power and memory for other instruments.

Carl Sagan had a different idea.

Sagan, who was a member of the Voyager imaging team, spent years lobbying NASA to turn the spacecraft around for one last look at home. He knew the image wouldn't have much "scientific" value. From 3.7 billion miles away, you can't see clouds. You can't see continents. You can't see the impact of climate change or the lights of cities. From that distance, Earth is just a point of light. But Sagan understood the poetic value. He fought the bureaucracy. Some NASA leads worried the sun would fry the spacecraft’s sensitive vidicon cameras. It was a risk. Eventually, in early 1990, Richard Truly, the NASA Administrator at the time, gave the green light.

On February 14, 1990, Voyager 1 pointed its narrow-angle camera back toward the inner solar system. It took a series of 60 images to create a "Family Portrait" of the planets. Among them was the frame that changed everything.

What You’re Actually Seeing in the Picture of Earth from Voyager

When the data finally trickled back to Earth—transmitted at a bit rate that would make a 56k modem look like fiber optics—the team was met with a messy, streaked image. It isn't a "clean" photo.

📖 Related: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

The vertical bands of light across the frame aren't "beams" from space. They are artifacts caused by sunlight scattering inside the camera's optics. Because Voyager was so far away and relatively close (in angular terms) to the Sun, the glare was intense. By pure, poetic coincidence, Earth happened to be sitting right inside one of those scattered light beams. It looks like a spotlight from the heavens is pointing at us, but it’s just a trick of the lens.

The Technical Reality of 1990 Imaging

- Distance: 6 billion kilometers (about 3.7 billion miles).

- Camera: A slow-scan vidicon camera using a 1500mm focal length lens.

- Filters: The final image was a composite of blue, green, and violet filters.

- Size: Earth occupies less than 0.12 of a pixel.

Think about that. The entirety of our world—the oceans, the Himalayas, the Great Wall, your house—is contained in a fraction of a single pixel. It’s the ultimate lesson in perspective. We spend so much time obsessed with our "vast" empires and "global" problems. In this photo, the globe is a joke. It’s a speck.

Why This Image Still Matters in 2026

We live in an era of constant, high-res satellite feeds. You can pull up Google Earth and see the car parked in your driveway. We are saturated with images of our planet. So why does this blurry, 36-year-old picture of Earth from Voyager still go viral every few months?

Because it’s the only photo that shows us our place in the neighborhood.

When we see the Blue Marble from the Moon, we see a neighbor. When we see the Pale Blue Dot, we see a lonely outpost. There is nothing else in the frame. No other habitable planets. No signs of life nearby. Just cold, dark, oppressive space. It highlights the "oneness" of humanity. As Sagan famously wrote in his book Pale Blue Dot, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. It’s just us.

This realization often triggers what psychologists call the "Overview Effect." Usually, this is experienced by astronauts who see Earth from orbit and suddenly feel a profound sense of global citizenship. But the Voyager photo offers a "Deep Space Overview Effect." It’s a reminder that our political borders are invisible and our self-importance is delusional.

👉 See also: Why Backgrounds Blue and Black are Taking Over Our Digital Screens

The Logistics of the "Family Portrait"

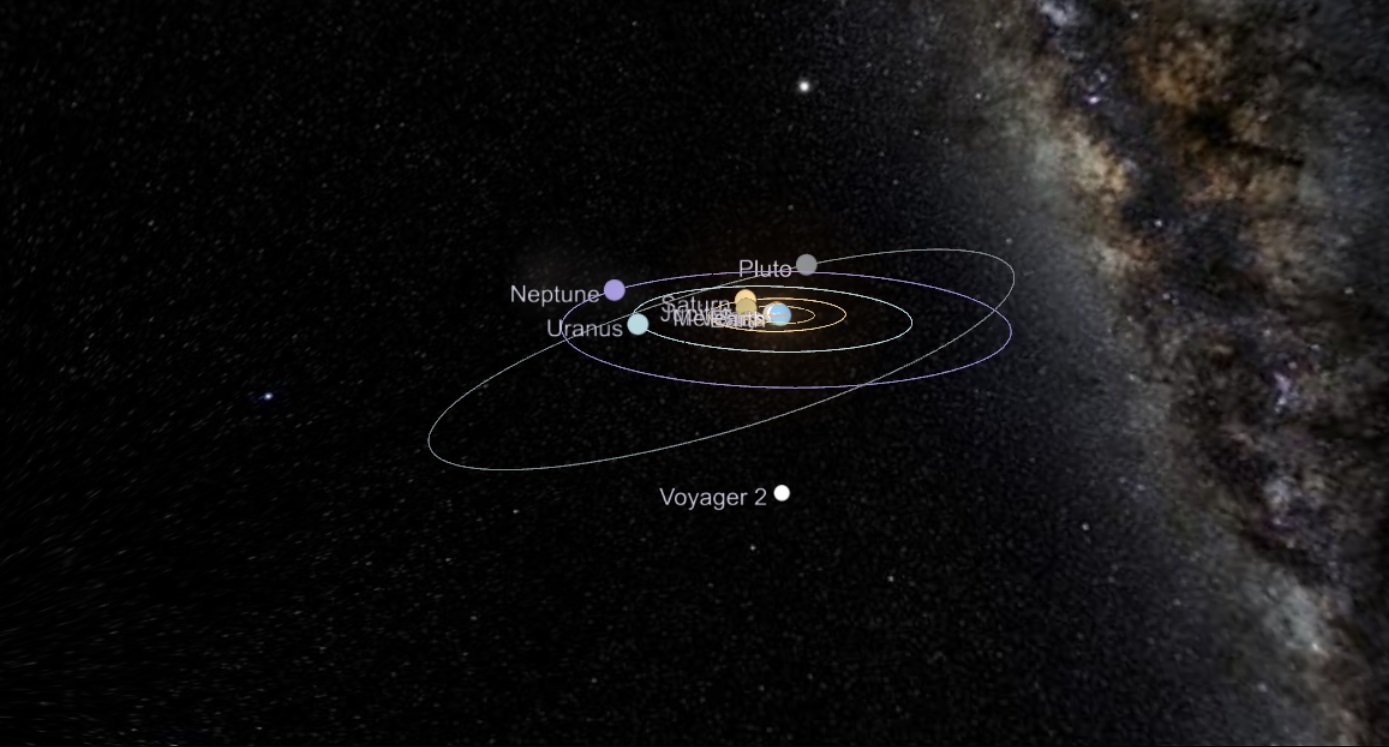

Voyager didn't just snap Earth. It took photos of Neptune, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, and Uranus. Mercury was too close to the sun to see, and Mars was lost in the glare. Pluto (still a planet back then!) was too dim.

The effort to coordinate these shots was monumental. Mission controllers had to send commands hours in advance. The spacecraft had to steady itself. The data had to be stored on a digital tape recorder—yes, an actual tape—and then beamed back to the Deep Space Network on Earth. It took months to process these images into something the public could understand. When the Earth photo was finally released in May 1990, it didn't immediately become an icon. It took time for Sagan's narration and the sheer weight of the distance to sink into the public consciousness.

Common Misconceptions About the Photo

People get things wrong about this shot all the time.

First, many people think it’s a photo of the "whole" Earth. It isn't. It’s a photo of a point of light. If you printed the original image at full size, Earth would be a tiny smudge you’d probably try to wipe off with a microfiber cloth.

Second, some believe Voyager 2 took it. Nope. Voyager 2 was busy looking at Neptune and Triton. Voyager 1 was the one that climbed "above" the ecliptic plane of the planets, giving it the top-down vantage point necessary to look back at the sun's family.

Third, people often confuse it with the "Earthrise" photo taken from the Moon. Earthrise is beautiful and shows the curved horizon of the lunar surface. The picture of Earth from Voyager has no surface, no horizon, and no context other than the sunbeams and the void. It’s much, much lonelier.

✨ Don't miss: The iPhone 5c Release Date: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insights: How to Use This Perspective

Knowing the history of this image is one thing; letting it change your mindset is another. Here is how to actually apply the "Pale Blue Dot" philosophy to your daily life:

1. The "Pixel Test" for Stress

Next time you're overwhelmed by a work deadline or a social media argument, visualize the Voyager image. Realize that the person you're arguing with, the office building you're stressed about, and the bills on your desk are all located on that 0.12-pixel dot. It doesn't make your problems "not real," but it makes them smaller. Perspective is a choice.

2. Support Planetary Defense and Science

The photo proves we are on an island. There is no "Planet B" ready for us. This makes funding for near-Earth object (NEO) tracking and environmental science a survival necessity, not a luxury. Support organizations like The Planetary Society (founded by Sagan) that continue this advocacy.

3. Digital Archiving

The Pale Blue Dot was almost lost because of technology shifts. NASA had to go back and "re-process" the image in 2020 for the 30th anniversary using modern software to extract more detail from the old data. Take a lesson: backup your important "human" moments. The data we create today is just as fragile as the tape reels Voyager used in the 90s.

4. Practice "Saganism" in Communication

Carl Sagan took a technical, cold, distant data point and turned it into a story about human connection. Whether you’re in business or education, remember that facts alone don't move people. Meaning does. Voyager taught us that even a single pixel can tell the story of everything we've ever been.

The Voyager 1 spacecraft is currently over 15 billion miles away. Its power sources are dying. Eventually, it will go silent, drifting forever through the galaxy. But it left us with a mirror. In that picture of Earth from Voyager, we don't see the world as we imagine it—mighty and endless. We see it as it truly is: a tiny, beautiful, and incredibly fragile home that we're lucky to have.

To see the updated, high-definition remaster of the Pale Blue Dot, visit the official NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) archives. Comparing the 1990 original to the 2020 "re-processed" version shows just how much "noise" was actually present in the original data and how modern imaging can find beauty in the static.

Check the current coordinates of Voyager 1 via NASA's "Eyes on the Solar System" real-time tracker to see just how far that little camera has traveled since it took our picture. It’s a distance that continues to grow every second, making that pale blue dot even smaller in the rearview mirror.