It’s 1986. You’re standing in the middle of a brown, pixelated field. There are no waypoints. No glowing yellow lines on the floor telling you where to walk. No "Quest Log" tucked into a neat little menu. You just have a tiny guy in a green tunic and a shield that looks like a cracker. This was the birth of the original Link Legend of Zelda experience, and honestly, modern gaming still hasn't quite figured out how to replicate that specific brand of "figure it out or die" magic.

Nintendo didn't just make a game; they made a mystery box. Shigeru Miyamoto famously wanted to capture the feeling of being a kid exploring the hillsides around Kyoto, stumbling upon caves and not knowing what was inside. Most games back then were linear. You went left to right, like Mario, or you stayed on one screen and shot bugs, like Galaga. Then Zelda happened. It told you to go wherever you wanted, which was terrifying. It still is.

The gold cartridge that changed everything

When you held that gold NES cartridge, it felt heavy. It felt important. Most people don't realize that the original Link Legend of Zelda was actually the first home console game to feature an internal battery for saving data. Before this, you had to write down long strings of gibberish passwords or just leave your NES on overnight and pray your mom didn't unplug it to vacuum the rug.

Being able to save meant the world could be huge. And it was. The overworld consisted of a 16-by-8 grid of screens. That sounds small now, but in 1986, it was an ocean. You’ve got the Lost Woods to the west, the Death Mountain range to the north, and a graveyard that would absolutely wreck your day if you touched the headstones.

The game didn't care if you were prepared. You could wander into a high-level area immediately and get annihilated by a Blue Lynel. That’s the beauty of it. It treated the player like an adult. It assumed you were smart enough to realize that if you're getting killed in one hit, you should probably go somewhere else.

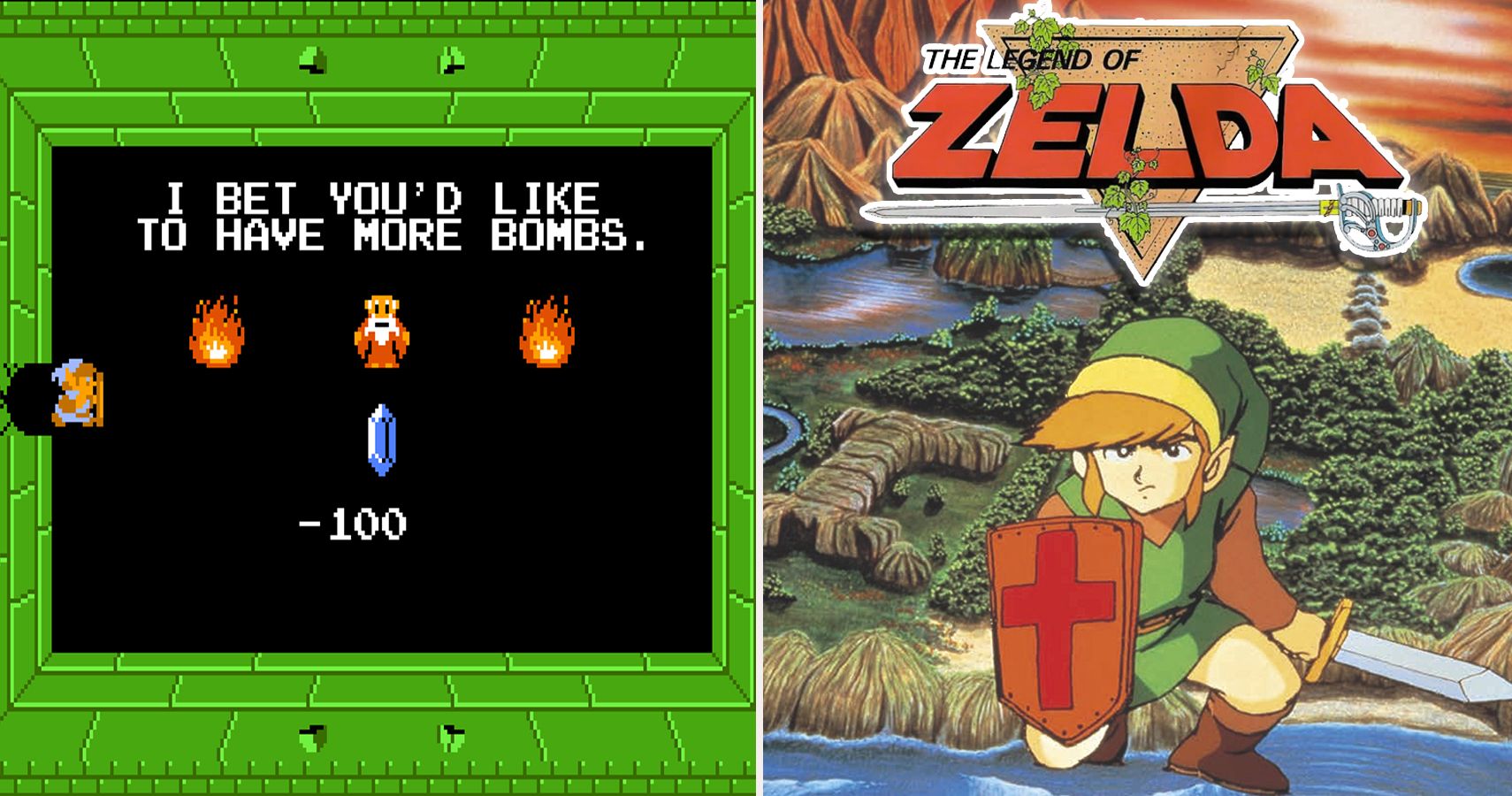

That old man in the cave wasn't being helpful

"It's dangerous to go alone! Take this."

We’ve seen the memes. We’ve seen the t-shirts. But think about that moment for a second. The game starts, and Link has nothing. He can't even punch. If you don't walk into that first cave, you are literally defenseless. It’s a bold design choice that forces interaction.

But here is the thing people forget: the old man gives you the Wooden Sword, the weakest weapon in the game. It’s barely a toothpick. To get the White Sword or the Magical Sword, you had to actually have a certain number of heart containers. The game gated your power behind your exploration. You couldn't just "grind" levels because there was no XP. You had to find the hearts. You had to find the secrets.

Secrets that weren't actually secrets

Back in the day, if you wanted to beat the original Link Legend of Zelda, you needed a physical map. Nintendo Power magazine became a household staple basically because of this game. You’d hear rumors at school. "Hey, if you burn the fifth bush from the left on that one screen, a staircase appears."

🔗 Read more: Straight Sword Elden Ring Meta: Why Simple Is Often Better

It sounded like playground lies. Except, in Zelda, it was usually true.

The sheer density of secrets is staggering. Almost every screen has something. A bombable wall. A burnable bush. A rock you can push. There was no visual hint that a wall was bombable. No cracks. No "X" marks the spot. You just had to try it. This created a community of players talking to each other, which is exactly what Miyamoto wanted. He wanted the game to exist outside of the TV screen.

The Second Quest is the ultimate "gotcha"

Most people beat Ganon, saw the credits, and thought they were done. Then they saw the little Triforce icon next to their save file.

The Second Quest is legendary for being brutal. It’s not just a "Hard Mode" where enemies have more health. No, Nintendo actually moved the dungeons. They changed the layouts. They made it so you could walk through walls. It turned your knowledge of the world against you. If you thought you knew where Level 4 was, you were wrong. It's somewhere else now, and the entrance is hidden under a bush you'd never think to burn.

Honestly, it’s a bit mean. But it’s also brilliant. It doubled the life of the game using almost no extra memory.

The music that won't leave your head

Koji Kondo is a genius. Period. The Overworld Theme is probably the most recognizable piece of music in gaming history. But did you know it was a last-minute replacement?

Originally, Kondo wanted to use Maurice Ravel’s Boléro. He thought the repetitive, building rhythm fit the idea of an epic journey. But at the very last second, Nintendo realized the copyright for Boléro hadn't expired yet. Kondo had to write a brand new theme in about a day. He sat down and cranked out the Zelda theme we know today.

It’s better than Boléro. It’s adventurous, heroic, and just a little bit lonely. It captures the essence of the original Link Legend of Zelda perfectly. It’s the sound of a kid in a backyard with a stick, imagining they’re a hero.

💡 You might also like: Steal a Brainrot: How to Get the Secret Brainrot and Why You Keep Missing It

Why it still holds up (and why it doesn't)

Let’s be real for a minute. Playing this game in 2026 can be frustrating. The hit detection is weird. Link can only move in four directions—no diagonals. If you want to use an item, you have to pause, select it, unpause, use it, and then repeat the whole process to go back to your boomerang. It’s clunky.

But the core loop? That’s untouched.

- Discovery: Finding a secret shop behind a waterfall.

- Progression: Getting the Raft and suddenly being able to reach the islands in the lake.

- Challenge: The Darknuts in the later dungeons are still some of the most stressful enemies in any Zelda game.

Modern games like Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom are essentially just high-definition versions of the original Link Legend of Zelda. They went back to that "see that mountain? go there" philosophy. After decades of Zelda games becoming more and more linear—think Skyward Sword with its constant hand-holding—the series finally returned to its roots. It turns out, we don't want to be told where to go. We want to get lost.

The dungeon designs are abstract art

The dungeons in the first game aren't "places" like they are in later games. They aren't fire temples or forest sanctuaries. They are shapes. If you look at the maps, they are shaped like an Eagle, a Moon, a Manji, and a Lizard.

Level 9, Death Mountain, is a sprawling mess of rooms that feels like a literal descent into madness. There are no puzzles in the modern sense. You don't pull levers or light torches to open doors. Usually, you just kill everything in the room or push a block. It’s visceral. It’s about survival, not brain-teasers.

The localization was a mess

We have to talk about the translation. It’s iconic because it’s so bad. "Grumble, Grumble." "Amesylt is the name of the river." "Go to the next room."

The most famous one, of course, is "Dodongo dislikes smoke." This was the game’s cryptic way of telling you to bomb the boss. It’s barely English, but it added to the mystique. Because the clues were so vague, players felt like they were deciphering an ancient language. It made the world feel older and more alien than it probably was.

Real world impact: The legacy of Link

Without this game, we don't have Dark Souls. Hidetaka Miyazaki has cited the feeling of exploration and the lack of hand-holding in early games as a major influence. The original Link Legend of Zelda taught a generation that it's okay to fail. It taught us that the world is big and scary, but if you look under enough rocks, you’ll find the tools to conquer it.

📖 Related: S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2 Unhealthy Competition: Why the Zone's Biggest Threat Isn't a Mutant

Even the "Zelda layout"—the idea of an overworld connecting several themed dungeons—became the blueprint for the entire Action-Adventure genre. Every time you play an open-world game and see a strange structure in the distance that makes you want to stop what you're doing and investigate, you're experiencing the DNA of 1986.

How to play it today without losing your mind

If you’re going back to play it now, don't feel guilty about using a map. People used maps in 1986. They were included in the box! If you try to play it completely blind, you will spend ten hours burning every single bush in Hyrule, and that’s not fun. That’s a chore.

- Get a map of the overworld. Just the terrain, not the secrets.

- Use save states. The original game’s "continue" system is punishing. You start back at the beginning of the world with only three hearts, no matter how many containers you have. It’s tedious.

- Talk to people. Not the NPCs (they’re mostly useless), but actual people who have played it. Or read old forums.

- Don't rush to Level 1. Explore first. Find some extra hearts. Get the Blue Candle from the shop so you can light up dark rooms and burn bushes.

The original Link Legend of Zelda isn't just a museum piece. It’s a masterclass in minimalist design. It gives you a sword, a goal, and a giant world, and then it gets out of your way. That’s something more games should try doing.

Basically, the game is a Rorschach test for gamers. Some people see a dated, confusing mess. Others see the purest expression of adventure ever put on a silicon chip. Both are probably right, but only one group gets to find the power bracelet hidden under a statue.

If you've never sat down and actually finished it, you're missing out on the foundation of the hobby. It’s hard, it’s weird, and the "Gleeok" boss will make you want to throw your controller across the room. But when you finally assemble that Triforce of Wisdom and face Ganon in the dark, it feels earned in a way that modern "follow the objective marker" games rarely do.

The legend began here. It hasn't really ended since.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Locate a Copy: The easiest way to play is via the Nintendo Switch Online NES library. It includes a "SP" (Special) version that starts you with all equipment if you just want to see the sights without the grind.

- Digital Archaeology: Look up the original 1986 instruction manual online. It contains beautiful hand-drawn art and lore that isn't in the game itself, providing essential context for the world-building.

- Map it Out: If you want the authentic experience, grab a piece of graph paper. Drawing your own map as you navigate the dungeons is a meditative way to experience the game's intentional layout.