The plastic is heavy. That’s the first thing you notice when you pick up a Western Electric 2500. It doesn’t feel like the hollow, disposable tech we carry in our pockets today. It feels like a weapon, or maybe a piece of industrial machinery. For decades, the old push button telephone was the literal backbone of global communication, a sturdy beige box that sat on kitchen counters and office desks, waiting for the tactile "thwack" of a finger hitting a plastic square.

It changed everything.

Before the push button arrived, you had to wait. You stuck your finger in a hole, dragged a wheel clockwise, and let it spin back. Do that seven times. It took forever. Then came Dual-Tone Multi-Frequency (DTMF). That’s the fancy name for Touch-Tone. It wasn't just a convenience; it was a revolution in how machines talk to each other.

The day the rotary died

Bell Labs didn't just wake up one day and decide buttons were cooler than dials. They had a problem. As the phone network grew, the slow pulses of rotary dials were clogging up the switching offices. They needed speed.

In 1963, at the World's Fair, AT&T introduced the 1500 model. It only had ten buttons. No pound sign. No star key. Those came later when engineers realized we might need them to interact with computers. People were skeptical. They’d spent fifty years circling their fingers, and now they were told to jab at a grid? It felt weird. But once you realized you could dial a number in two seconds instead of twelve, there was no going back.

The old push button telephone wasn't just a phone; it was the first computer terminal most people ever owned.

How that "Beep" actually works

Every time you hit a key, you're playing a chord. It’s not just one tone. If it were, the system might get confused by a human voice or a stray noise on the line. Instead, DTMF uses a grid.

When you press "1," the phone sends two simultaneous frequencies: 697 Hz and 1209 Hz. The "Low Group" handles the rows, and the "High Group" handles the columns. This was a stroke of genius by researchers like Leo Schenker. By using two tones that aren't harmonically related, they ensured that the sound of a dog barking or a person coughing wouldn't accidentally dial Grandma.

Think about that. Your old push button telephone was performing real-time signal processing decades before the word "digital" meant anything to the average person. It’s basically a musical instrument tuned to talk to a giant mechanical brain in a windowless building downtown.

The legendary Western Electric 2500

If you close your eyes and picture an old push button telephone, you’re probably seeing the Western Electric 2500. It is the gold standard. It was built to be leased, not bought. Because the phone company (Ma Bell) owned the hardware, they wanted it to last forever so they wouldn't have to send a repairman out.

These things are tanks.

- The chassis is heavy-gauge steel.

- The bells—actual physical brass bells—are loud enough to wake the dead.

- The "Carbon Pile" microphone in the handset makes your voice sound warm, if a bit fuzzy.

- The coil cord is thick enough to jump-start a car (mostly).

I’ve seen these phones dropped down flights of stairs only to be plugged back in and work perfectly. Compare that to a modern smartphone that shatters if you look at it wrong. There’s a certain dignity in a piece of tech that refuses to die.

Why we can't let go of the "Click"

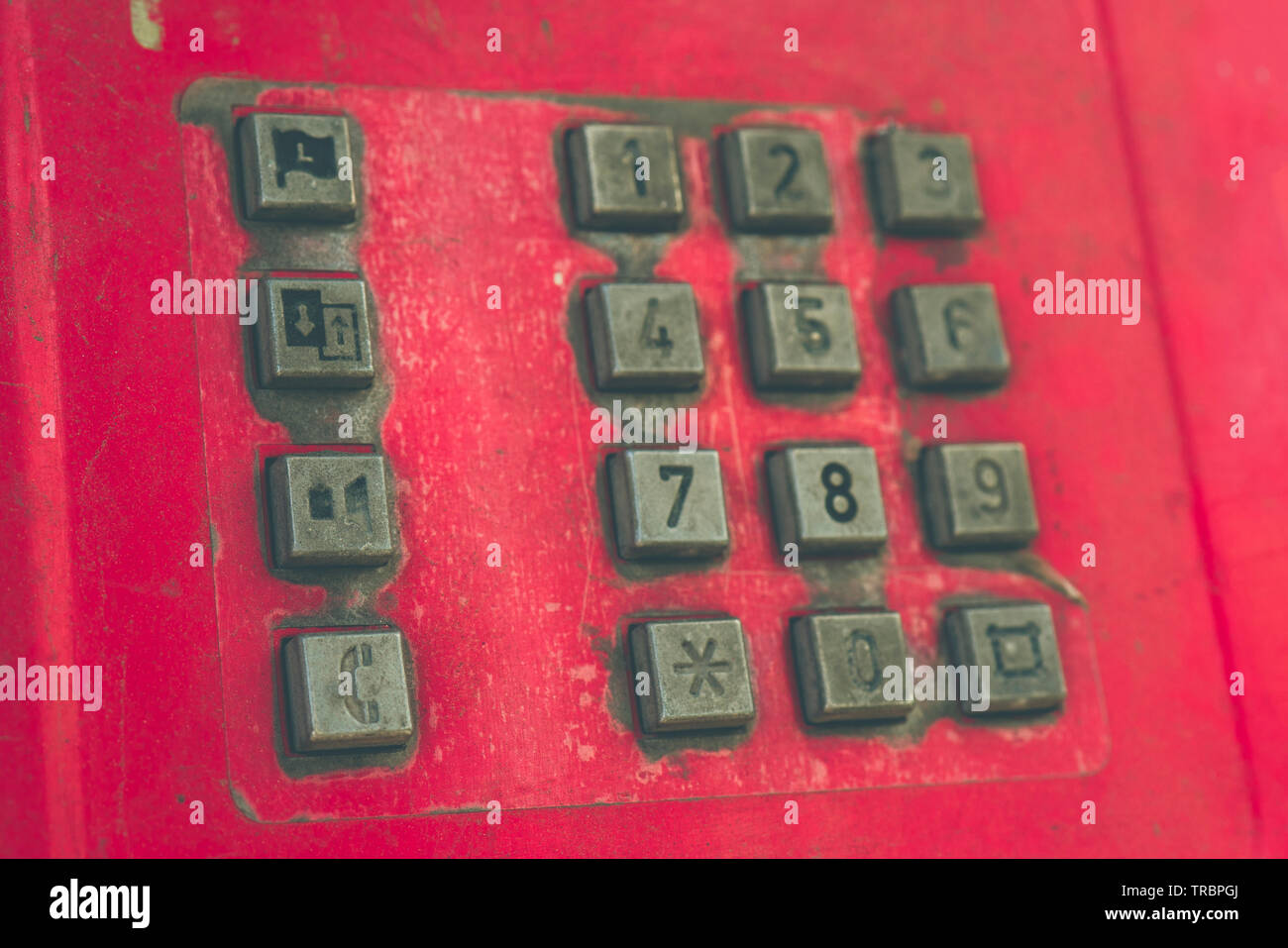

There is a psychological component to the old push button telephone that modern touchscreens can't replicate. It's the haptic feedback. When you press a button on a 2500-series set, you feel the spring compress. You hear the mechanical snap. It’s definitive.

Modern UI designers spend millions of dollars trying to make glass feel like those buttons. They use haptic motors and "taptic" engines to simulate that physical feedback. We spent forty years perfecting the button only to throw it away for a flat piece of glass, and now we're desperately trying to get back to where we started.

Honestly, dialing a number on an old push button telephone is satisfying in a way that "tapping" a contact list just isn't. It’s an intentional act. You had to know the number. You had to remember it. The muscle memory of a seven-digit phone number lived in your fingertips.

The rise of the "Smart" phone (The 1980s version)

By the 1980s, the old push button telephone started getting weird. This was the era of the "Feature Phone." Suddenly, everyone wanted a phone that looked like a sports car, or a burger, or a transparent box filled with neon lights.

👉 See also: Why the GoPro Hero 4 Session Still Matters Years Later

But under the hood, they were all trying to be the Western Electric 2500.

We saw the introduction of:

- Redial buttons: The height of luxury. No more manual re-entry after a busy signal.

- Mute switches: Perfect for yelling at the kids while staying on the line with your boss.

- Programmable speed dial: You could save ten numbers! Ten! It felt like the future.

This was also when the pound (#) and star (*) keys finally found their purpose. Before the 80s, they were mostly decorative. But then came automated menus. "Press 1 for sales." We suddenly needed those extra buttons to navigate the growing digital world. The old push button telephone became our remote control for the entire planet.

Phreaking and the dark side of tones

You can't talk about these phones without mentioning the "phreaks." In the 60s and 70s, people like John Draper (Captain Crunch) and even the founders of Apple, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, figured out that if you could mimic the tones of the phone system, you could control it.

They used "Blue Boxes" to emit a 2600 Hz tone, which told the network a call had ended, but kept the line open. Then, they’d use the tones of the old push button telephone to route their own calls for free.

It was the first real "hack." And it was only possible because the system trusted the tones coming out of your handset. The phone company assumed the hardware was the gatekeeper. They didn't realize that a kid with a plastic whistle from a cereal box could be just as powerful as a professional operator.

What happened to the quality?

If you go to a big-box store today and buy a "landline" phone, it’ll weigh about four ounces. It’ll feel like a toy. That’s because once AT&T was broken up in 1984, the incentive to build indestructible hardware vanished.

Planned obsolescence took over.

👉 See also: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Admission: What the Data Actually Says About Getting In

The old push button telephone went from being an appliance you kept for thirty years to a piece of electronic junk you replaced every eighteen months. The sound quality dipped. The buttons started sticking. The bells were replaced by tinny electronic chirps that sound like a dying cricket.

This is why there’s such a massive market for "refurbished" vintage phones today. People are tired of flimsy plastic. They want that 1970s weight. They want the satisfaction of hanging up—the physical act of slamming the handset onto the base to end a frustrating conversation. You just can't "slam" an iPhone. It doesn't have the same emotional release.

Troubleshooting your vintage find

If you find an old push button telephone at a thrift store or in your grandmother's attic, don't throw it away. Most of the time, they still work. Even on modern digital lines (VOIP), these phones are surprisingly resilient.

First, check the modular jack. If it’s a 2500 model from the late 70s, it’ll have the standard RJ11 plug we still use today. If it's older, it might have a four-prong plug. You can buy an adapter for five dollars online.

Second, listen to the tones. If you press a button and hear a "click-click-click" instead of a beep, you have a pulse-only phone. These are rarer in the push-button world, but they exist. They won't work for navigating automated menus, but they’ll usually still make calls.

Third, clean the contacts. If the buttons are sticky, a little bit of isopropyl alcohol on a Q-tip usually does the trick. These machines were designed to be serviced. You can actually unscrew the casing and see the wires. No glue. No proprietary screws. Just honest engineering.

Moving forward with vintage tech

We live in an era of digital fatigue. Our phones are portals to work, stress, and endless scrolling. The old push button telephone is different. It does one thing. It handles a voice.

When that phone rings, it’s an event. You don't see a caller ID (usually). You don't see a notification. You just hear the strike of metal on metal. There is a peace in that simplicity.

If you want to bring a bit of that tactile history into your home, start by looking for "Western Electric" or "ITT" stamps on the bottom of the casing. Avoid the 90s replicas made of thin plastic. Look for the heavy stuff.

Take these steps to integrate a classic set into your modern life:

- Verify your line: Ensure your internet provider's modem supports "POTS" (Plain Old Telephone Service) via the "Phone" jack on the back.

- Get a DTMF-to-Pulse converter: If you happen to buy a very early model that doesn't "beep," this little box will translate your button presses for modern digital switches.

- Replace the handset cord: Most "old" phone problems are actually just a frayed cord. They are cheap and still widely available in various colors.

- Ditch the clutter: Put the phone in a place where you actually want to talk. A quiet corner. A study. Treat the phone call as an activity, not a distraction.

There is something deeply grounding about holding a piece of history that still functions exactly as it did sixty years ago. The old push button telephone isn't just a relic; it's a reminder that sometimes, we got it right the first time.