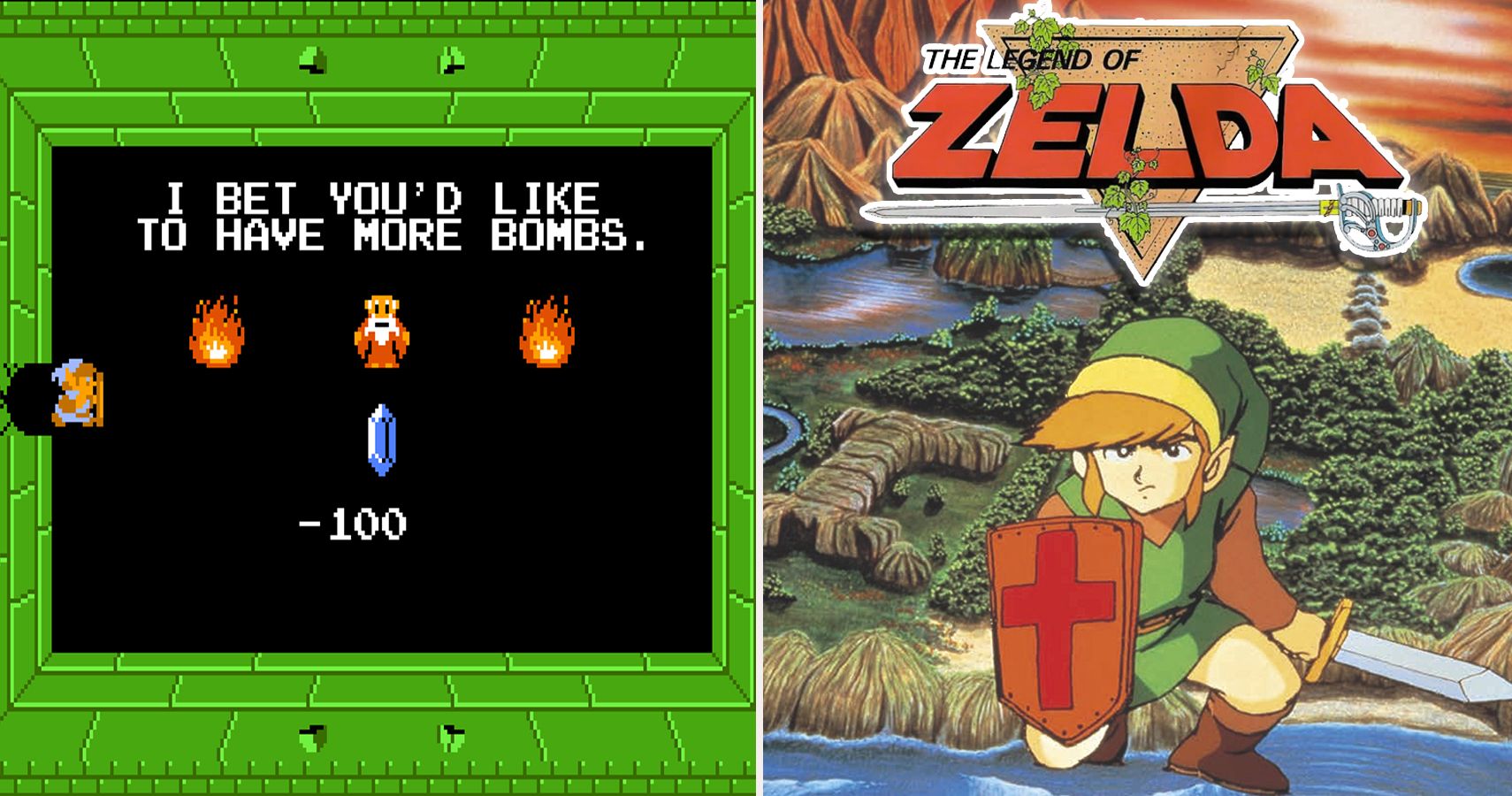

Walk into a dimly lit room in 1986. You’re staring at a CRT television that’s humming with static electricity. You push a gold-colored plastic cartridge into a grey box. There is no tutorial. No map marker. No floating waypoint telling you to "Go Here." There is only a small sprite in a green tunic, a wooden sword, and a cave that says, "It’s dangerous to go alone! Take this." This was the birth of the old Legend of Zelda, and honestly, it’s a miracle we ever finished it without the internet.

Back then, the game wasn't about "content loops" or "engagement metrics." It was a literal labyrinth of secrets that relied on schoolyard rumors. Did you know you could burn that specific bush to find a hidden staircase? Someone’s older brother told you that. It was communal. It was cryptic. Most importantly, it was lonely in a way modern games rarely dare to be.

The Brutal Simplicity of the Famicom Days

Modern players coming from Breath of the Wild or Tears of the Kingdom often find the 1986 original—and even its direct sequels—totally jarring. It’s hard. It’s unforgiving. You die, and you’re sent back to the start of the screen with three hearts and a dream. Shigeru Miyamoto famously wanted to capture the feeling of exploring the hillsides and caves of his childhood in Sonobe, Japan. He succeeded perhaps too well.

The old Legend of Zelda on the NES didn't just give you a world; it dared you to survive it. There’s this specific tension in the first game where every screen is a tactical puzzle. Those Blue Darknuts in the Level-5 dungeon? They still give veteran players nightmares. They don't move in predictable paths. They turn on a dime. You have to poke them in the side, retreating like a coward, hoping your wooden shield catches the flying swords. It wasn’t about being a superhero. It was about being a kid who was way out of his depth.

Why Zelda II Is the Black Sheep (and Why That’s Wrong)

Then came The Adventure of Link. People hate this game. Or they love it with a burning passion that defies logic. It swapped the top-down perspective for a side-scrolling action-RPG hybrid that felt more like Castlevania than Zelda. It introduced a magic meter, towns with NPCs that actually talked, and a combat system that required genuine frame-perfect timing.

🔗 Read more: Gothic Romance Outfit Dress to Impress: Why Everyone is Obsessed With This Vibe Right Now

If you want to understand the DNA of the old Legend of Zelda, you have to look at the combat in Zelda II. High block. Low block. Jump stab. It was mechanical. It was exhausting. It also introduced Dark Link, a concept that would haunt the franchise for decades. Most people quit at Death Mountain because the bridges are narrow and the Goriya throw hammers that seem to defy physics. But if you push through, you realize this was the moment the series decided it could be anything. It wasn't stuck in one perspective.

The 16-Bit Perfection of A Link to the Past

By 1991, the SNES arrived and gave us A Link to the Past. This is widely considered the peak of the "old" style before everything went 3D. It perfected the "two-world" mechanic. You had the Light World and the Dark World. It was a genius bit of technical wizardry. By reusing the map layout but changing the assets and puzzles, the developers at Nintendo EAD effectively doubled the game's size without needing massive amounts of extra storage on the cartridge.

It’s also where the lore got heavy. We got the Seven Sages. We got the Master Sword in the Lost Woods, surrounded by those soft, foggy rays of light. Koji Kondo’s score went from "catchy 8-bit tunes" to "orchestral masterpieces" that felt like a real epic.

Honestly, the old Legend of Zelda games were masters of "Show, Don't Tell." You didn't get a 10-minute cutscene explaining Ganondorf’s tragic backstory. You just saw a giant pig-demon with a trident and knew he had to go. There’s a purity there. You weren't a "Chosen One" because a prophecy said so in a glowing UI menu; you were the Chosen One because you were the only person brave enough to walk into the mountain.

💡 You might also like: The Problem With Roblox Bypassed Audios 2025: Why They Still Won't Go Away

The Game Boy Wonders

We can't talk about the classics without mentioning Link’s Awakening. It’s weird. It’s surreal. It features Mario enemies like Goombas and Piranha Plants for no clear reason. It takes place on Koholint Island, a place that technically shouldn't exist. This was the first time the series got emotional. When you realize that waking the Wind Fish means everyone you've met—the girl Marin, the weird kids in the village—will vanish like a dream... it hits hard. Even in 8-bit monochrome, that ending felt more significant than most modern AAA storylines.

The Myth of the "Impossible" Difficulty

A lot of people say the old Legend of Zelda is too hard for modern audiences. That’s a bit of a misconception. It’s not "hard" like a Soulslike game where you need 100% reflexes. It’s "hard" because it expects you to pay attention.

If an NPC says, "Go North, West, South, West" in the Lost Woods, they aren't kidding. If you don't have a notebook next to you, you're going to get lost. That's the secret sauce. The game lived outside the console. It lived on your coffee table in the form of hand-drawn maps and scribbled notes.

- Exploration was the primary mechanic, not the combat.

- Item-based progression meant every chest felt like a character level-up.

- Non-linear paths allowed for "sequence breaking" before that was even a term.

You could technically go into Level 3 before Level 2. You could grab the White Sword early if you knew the secret heart container locations. It respected the player's intelligence. Or, at the very least, it didn't treat you like you were five years old.

📖 Related: All Might Crystals Echoes of Wisdom: Why This Quest Item Is Driving Zelda Fans Wild

What We Can Learn from the Classics

Looking back at the old Legend of Zelda era—roughly 1986 to 1993—it’s clear that the limitations of the hardware forced better design. Because they couldn't make the grass look realistic, they had to make the puzzles interesting. Because they couldn't have voice acting, the music had to carry the emotional weight.

There's a reason Nintendo keeps going back to these roots. A Link Between Worlds on the 3DS was a direct love letter to the SNES era. Even Breath of the Wild used a 2D prototype based on the original NES game to test its physics engine. The foundation is rock solid.

If you’re looking to dive back into these gems, don’t use a guide—at least not at first. Get a piece of graph paper. Draw the rooms. Feel the frustration of getting lost. Because the moment you finally find that hidden dungeon or solve that block-pushing puzzle, the dopamine hit is way stronger than any "Quest Complete" notification.

Your Strategy for Revisiting the Classics

If you want to experience the old Legend of Zelda properly today, skip the "Perfect Walkthroughs" on YouTube. Instead, try these steps to recapture that 80s/90s magic:

- Play on a smaller screen: These games were designed for lower resolutions. Playing them on a 65-inch 4K TV can make the pixels look like giant blocks. Handheld mode on a Switch or an old-school CRT is the way to go.

- Limit your save states: The tension of the old games comes from the risk of losing progress. If you save every five seconds, the dungeons lose their teeth.

- Talk to everyone: NPCs in the old games don't waste words. If someone says "Symmetry is the key," they are literally giving you the answer to a puzzle three rooms away.

- Master the "Screen Scroll": In the NES version, enemies reset when you leave a screen. Use this to your advantage to despawn dangerous monsters.

The legacy of the old Legend of Zelda isn't just about nostalgia. It’s a masterclass in subtractive design. By taking away the hand-holding, Nintendo gave us a sense of true discovery that we're only just now starting to get back in the "open air" era of gaming. Go find a cave. Burn a bush. See what happens.