You're driving south through Florida, maybe stuck in the bumper-to-bumper nightmare that is I-95, and you see a small, faded sign pointing toward a narrow two-lane road. It looks like nothing. Just a strip of asphalt cutting through palm hammocks or old citrus groves. But that's the Old Dixie Highway. It was the first real attempt to connect the frozen North with the tropical South. Before the interstate system made travel a boring blur of gray concrete, the Dixie Highway was an adventure. Honestly, it was sometimes a disaster.

People forget that a century ago, "driving to Florida" wasn't a family vacation. It was an expedition.

The road didn't just happen. It was the brainchild of Carl Fisher, the same high-energy guy who developed Miami Beach and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He realized that if he wanted people to buy his swampy Florida real estate, they needed a way to get there that didn't involve a boat or a train. So, in 1914, he started pushing for a highway system that would link Chicago to Miami.

The Messy Reality of the Historic Old Dixie Highway

Calling it a "highway" back then was a bit of a stretch. It was more like a loose collection of existing wagon trails, paved streets, and muddy ruts stitched together by local governments who were desperate for tourist dollars. There wasn't one single road. Instead, there was an Eastern Division and a Western Division. They snaked through Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, and finally Florida.

🔗 Read more: Why To Sua Ocean Trench Upolu Samoa Still Lives Up to the Hype

It was chaotic.

One county might have beautiful brick paving, while the next county over was a literal swamp where your Model T would sink to the axles. This wasn't some federal project. The Dixie Highway Association basically functioned like a massive marketing firm, convincing towns to improve their local roads so they could be part of the official route. If you were a small-town mayor in Georgia in 1920, getting onto the Dixie Highway meant survival. It meant gas stations, motels (then called "tourist camps"), and diners.

Paving the Way with Brick and Sweat

If you find a surviving original segment today, look at the ground. In many spots, particularly in places like Bunnell or Mims in Florida, you’ll still see the Nine-Foot Brick Road. Why nine feet? Because that was exactly wide enough for one car. If you saw someone coming the other direction, one of you had to pull off into the sand. It was a game of chicken played at 20 miles per hour.

These bricks weren't just for show. They were a necessity. Florida's sugar sand is a nightmare for narrow tires. Without the bricks, the historic Old Dixie Highway would have just been a series of holes. You can still drive on some of these sections today, and the vibration—that rhythmic thump-thump-thump—is the exact same sound drivers heard in 1925.

Why the Route Changed Everything for the South

Before the highway, the South was largely isolated. The "Snowbird" phenomenon didn't exist. Once the road opened up, everything changed. It wasn't just about vacationers; it was about culture.

- The Rise of the Roadside Attraction: This is where the "Florida Man" energy arguably started. To get people to stop, locals started putting out alligators in pits and selling bags of oranges.

- The Pecan Stand Empire: If you’ve ever stopped at a Stuckey’s, you’re looking at the direct descendant of the roadside stands that lined the Dixie Highway in Georgia.

- The Great Migration: It wasn't just tourists going south. The highway provided a literal path for people moving North for industrial jobs, fundamentally shifting the demographics of cities like Detroit and Chicago.

Actually, the highway was a bit of a social minefield too. For Black travelers during the Jim Crow era, the Dixie Highway was dangerous. While the marketing promised "The Gateway to the South," the reality meant relying on the Green Book to find the few places that would actually serve you or let you sleep in a bed. It’s a part of the road's history that often gets glossed over in the nostalgia for "the good old days."

Tracking Down the Best Surviving Pieces

You can't "drive" the whole Dixie Highway anymore, at least not in a straight line. US-1 swallowed most of it. But if you're a history nerd, there are "ghost" sections that are hauntingly beautiful.

In Kentucky, look for the "Old Dixie" segments around the Cumberland River. The elevation changes are wild. In Florida, the stretch through the Tomoka Basin State Park north of Ormond Beach is spectacular. It's shaded by massive live oaks draped in Spanish moss. It feels like 1930. You half expect to see a rum-runner's car fly past you.

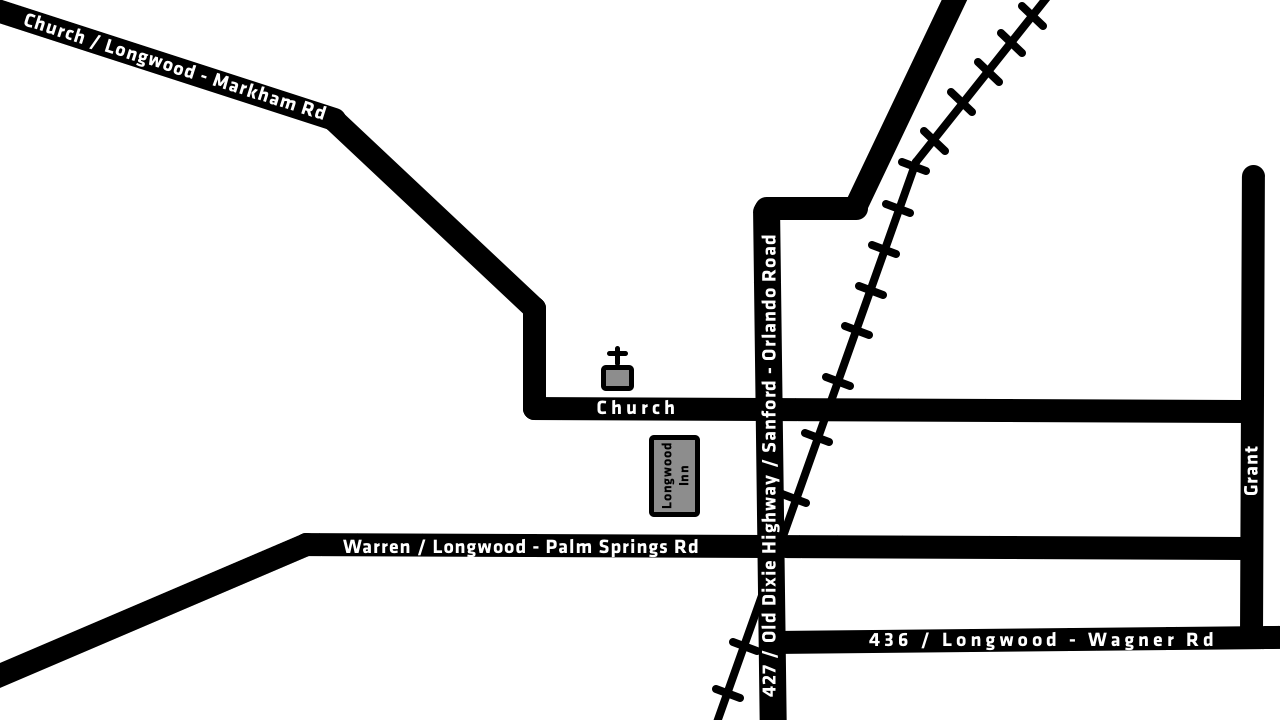

The road also goes by many names now. Depending on where you are, it might be called State Road 5, County Road 5A, or just "Main Street." In some towns, they’ve kept the Dixie Highway name as a point of pride, while others have changed it to avoid the historical baggage associated with the term "Dixie."

The Engineering Nightmare of the Mountains

Crossing the Appalachian Mountains in a car with mechanical brakes and no power steering was a feat of strength. The section near Rockwood, Tennessee, was notorious. It was a steep, winding climb that terrified drivers used to the flat plains of the Midwest. Local legends are full of stories of cars overheating and families camping out on the side of the road for days waiting for parts.

Modern Preservation vs. Progress

The fight to save the historic Old Dixie Highway is ongoing. Developers love the land it sits on. In many places, the old brick has been paved over with asphalt because it's cheaper to maintain. But groups like the Dixie Highway Association (the modern version) and local historical societies are fighting back.

They realize that once these roads are gone, the "sense of place" disappears too. An interstate highway looks the same in Ohio as it does in Florida. The Old Dixie Highway, however, changed with the landscape. It followed the curves of the earth.

If you're going to explore it, don't expect a fast trip. Honestly, if you're in a hurry, stay on the I-95. The Old Dixie Highway is for when you want to see the "Old Florida" that exists behind the strip malls. It’s for finding that one dive bar that’s been there since 1950 or the bridge that looks like it might not hold your SUV (it probably will, but it's okay to be nervous).

Actionable Tips for Your Road Trip

- Download Historical Maps: The original route is a jigsaw puzzle. Use the Dixie Highway Association's digital archives to find the exact turns.

- Look for the "DH" Markers: In some states, small concrete posts or painted signs still exist. They are rare. If you find one, take a photo; they’re disappearing.

- Support Roadside Weirdness: Stop at the orange groves. Buy the weird honey. Visit the small local museums in towns like Milton or Vero Beach. These places exist because of the highway.

- Check Your Tires: Some of the surviving brick sections are rough. Really rough. Make sure your suspension is up for it before you dive into a 20-mile stretch of 100-year-old paving.

- Respect Private Property: A lot of the "dead" ends of the highway now lead into private driveways or gated communities. Don't be that person.

The road is a living museum. It tells the story of how we became a mobile society. It shows our growth, our engineering mistakes, and our complicated social history. Driving it isn't just about the destination—it's about finally understanding why we started moving in the first place.