John Steinbeck was actually worried. By 1939, his novella was a massive hit, but Hollywood had a reputation for sanitizing the grit out of the Dust Bowl. Then Lewis Milestone stepped in. He didn't just film a book; he captured the desperate, dusty soul of the Great Depression. Honestly, it’s a miracle this movie exists in the form it does. The Of Mice and Men movie 1939 isn't just a black-and-white relic; it’s the blueprint for every "buddy" tragedy that followed. It’s raw.

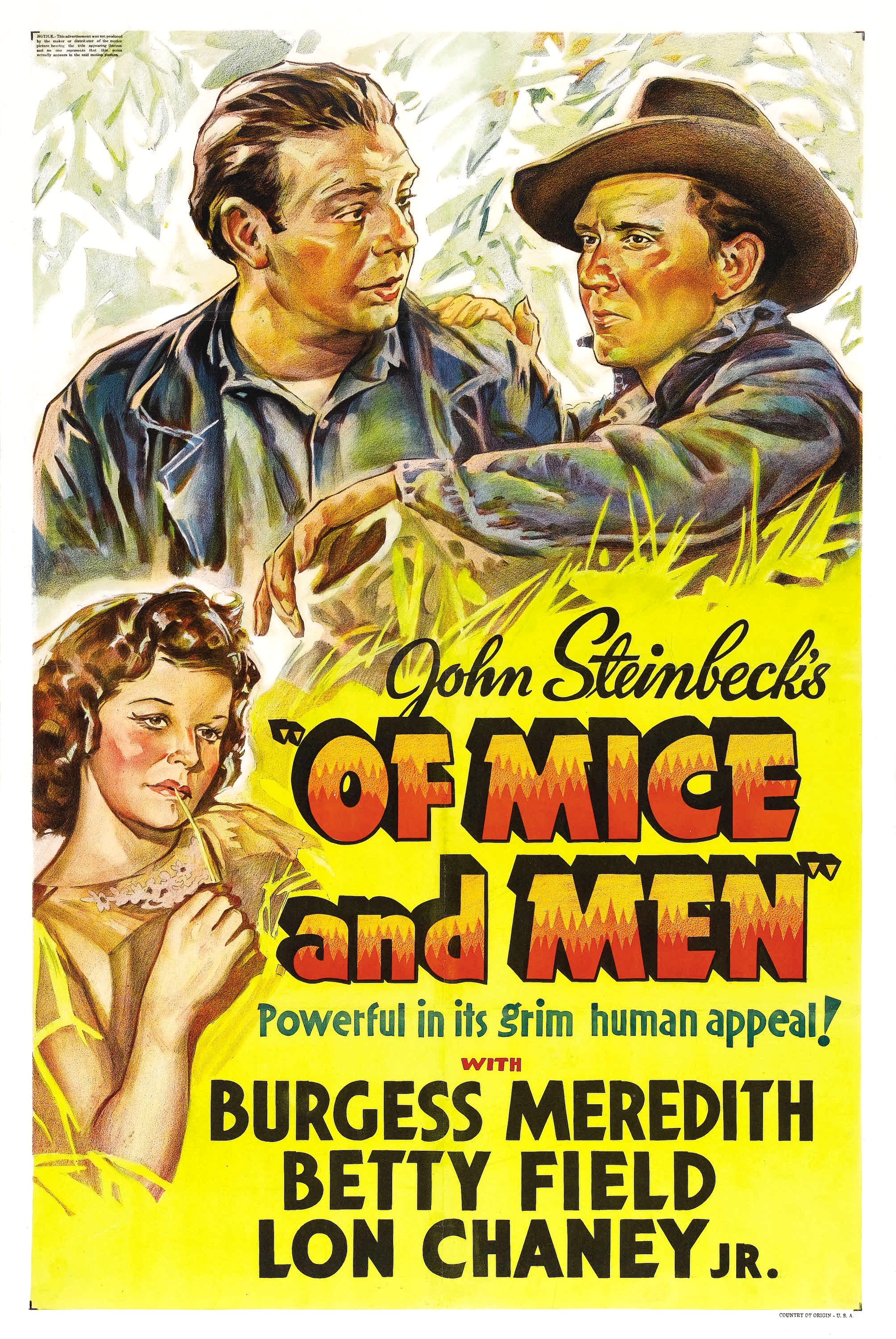

You've probably seen the 1992 version with Gary Sinise and John Malkovich. It’s fine. It’s pretty. But the 1939 original has this looming, claustrophobic dread that you just can't replicate with modern high-definition cameras. Burgess Meredith, decades before he became Rocky’s trainer, plays George Milton with a nervous, high-strung energy that feels incredibly human. He’s not a hero. He’s a guy just trying to survive the next ten minutes.

The Casting Gamble That Defined the Of Mice and Men Movie 1939

Casting Lon Chaney Jr. as Lennie Small was a massive risk. At the time, he was mostly known as the son of the "Man of a Thousand Faces." People expected him to be a horror icon, not a tragic figure with a cognitive disability. But Chaney’s performance is the heartbeat of the film. He doesn't play Lennie as a caricature. He plays him with a heavy, stumbling innocence that makes the eventual ending feel like a physical blow to the stomach.

Milestone made a weird choice for the era. He kept the dialogue sparse. He let the shadows in the barn do the talking. While other 1939 films like Gone with the Wind were going big and colorful, Milestone went small and dark. It paid off. The film was nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture. It lost out to Rebecca eventually, but the impact remained.

The Sound of Silence and Aaron Copland

The music matters. A lot. Aaron Copland composed the score, and if you know anything about American music, you know Copland is the sound of the prairie. But here, he twists those wide-open chords into something mournful. It’s one of the first times a film score was used to reflect the inner psychology of the characters rather than just telling the audience "now feel sad" or "now be scared."

It’s understated. Like a low hum of anxiety.

💡 You might also like: Dark Reign Fantastic Four: Why This Weirdly Political Comic Still Holds Up

Why This Adaptation Sticks to the Ribs

Most people forget how controversial the book was. It was banned constantly. The Of Mice and Men movie 1939 had to dance around the Hays Code—the strict censorship rules of the time—without losing the book's bite. It mostly succeeded. It kept the ranch hands' loneliness front and center. You see it in Candy, the old swamper who lost his hand and is terrified of being "put on the shelf" just like his old dog.

The scene where the dog is taken out to be shot? It’s arguably more devastating in 1939 than in any other version. The silence while the men wait for the gunshot is agonizingly long. Milestone lets it sit. He makes you sit in that room with George and Lennie and the crushing weight of their poverty.

A Different Kind of Curley’s Wife

In the novella, Curley’s wife doesn't even have a name. She’s just a "danger" to the men. The 1939 film, featuring Betty Field, gives her a bit more pathetic humanity. She’s bored. She’s trapped in a loveless marriage with a small man who has a massive chip on his shoulder. When she talks to Lennie in the barn, it’s not out of malice. It’s out of a desperate need for someone to just listen to her talk about her dreams of being in the "pitchers."

That’s the tragedy. Two lonely people find a moment of connection, and it destroys them both.

Technical Mastery in a Pre-Digital World

The cinematography by Norbert Brodine is stunning. He used deep focus before Citizen Kane made it the cool thing to do. You can see George’s face in the foreground and the vast, uncaring landscape of the Salinas Valley stretching out behind him. It emphasizes the theme: these men are tiny. They are insignificant. The world doesn't care if they get their "little fat of the land."

📖 Related: Cuatro estaciones en la Habana: Why this Noir Masterpiece is Still the Best Way to See Cuba

- The opening sequence isn't in the book. Milestone added a chase scene where George and Lennie are running from a posse in Weed.

- It sets the stakes immediately. You know they are running toward a disaster, not away from one.

- The lighting in the final scene by the river is stark. No soft focus. Just two men and a Luger.

Honestly, the ending of the Of Mice and Men movie 1939 is a masterclass in pacing. George’s hand shakes. Not in a theatrical way, but in a "I am about to lose the only thing I love" way. It’s a brutal, honest depiction of mercy killing that still sparks debates in classrooms today.

What Modern Viewers Get Wrong

A lot of folks think old movies are "slow." This one isn't. It’s 106 minutes of tight, purposeful storytelling. It doesn't waste time on subplots that don't matter. It stays on the ranch. It stays in the bunkhouse. It stays in the heads of these migrant workers.

People also tend to think that black-and-white film softens the blow of violence. If anything, it makes the darkness darker. The hay in the barn looks like gold in the light, but the shadows in the corners look like ink. It’s visually poetic in a way that modern color film often misses because it’s too busy trying to look "realistic."

The Legacy of the 1939 Version

Every time you see a story about a "big guy" and a "smart guy" trying to make it against the odds, you’re seeing the ghost of this movie. It influenced the noir genre. It influenced how Hollywood portrayed the American West—not as a place of cowboys and Indians, but as a place of labor, sweat, and broken dreams.

Steinbeck himself reportedly liked this version. That’s a rare feat for an author who usually hated what the studios did to his prose. He felt it captured the "rhythm" of his writing.

👉 See also: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

Key Takeaways for Film Buffs and Students

If you’re watching this for a class or just because you’re a cinephile, pay attention to the hands. The movie is obsessed with hands. Lennie’s "paws," Candy’s missing hand, Curley’s gloved hand, George’s restless hands. It’s a film about what we do with our labor and what happens when we can no longer work.

- Watch the eyes: Lon Chaney Jr. does more with his eyes than most actors do with a ten-minute monologue.

- Listen to the background: The sounds of the ranch—the horses, the clinking of horseshoes—create a sense of place that feels lived-in.

- Note the dialogue: It’s almost word-for-word from the stage play version, which Steinbeck also worked on.

Basically, if you want to understand the American psyche during its darkest economic hour, you have to watch this. It’s not just a "classic." It’s a warning. It’s a reminder that the "American Dream" has always been a fragile thing, easily crushed by a momentary lapse in judgment or a stroke of bad luck.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

To truly appreciate the Of Mice and Men movie 1939, you should compare it directly to the 1937 play-novelette. Notice how the film expands the world while keeping the dialogue sharp. You can find the film on several classic cinema streaming platforms or via the Library of Congress archives. Afterward, read Steinbeck’s "Harvest Gypsies" articles from 1936. They provide the real-world journalistic context for the migrant camps that inspired the setting of the film. Seeing the actual photos of the people Milestone was trying to portray will change how you view every frame of this 1939 masterpiece.